This rare 1927 Palmolive poster from our collection, not only stems from a very short-lived period of the brand, but was also designed by the most prolific commercial artist of Republican China. Follow along for a deep-dive into this golden age of Chinese advertising.

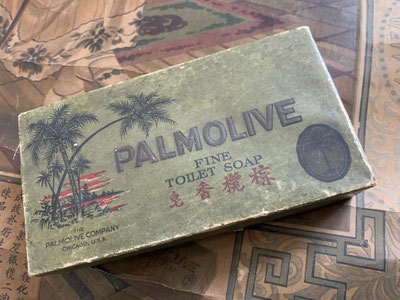

In 1898, the B.J. Johnson Co. from Milwaukee, Wisconsin introduced a pale, olive green colored, floating bar of soap made of coconut, palm and olive oils aggressively marketed under the brand name “Palmolive". The soap became very popular, due to an advertising campaign promoting it as the type of soap that would have been favored in ancient Egypt by the Pharaohs and especially "the Pharaoh's daughter“.

In just two years, Palmolive became the world’s best-selling soap. Following the brands success, the company changed its name to "Palmolive Soap Co." in 1917.

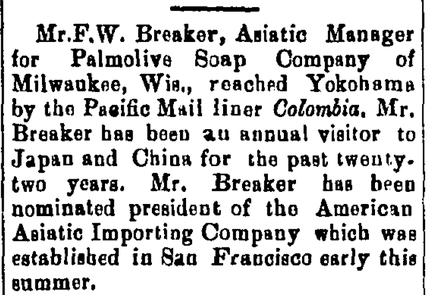

Represented by its Asiatic Manager F.W. Breaker, the B.J. Johnson Co. had been active in the Far-East almost since its inception.

However, it was only after the name change to Palmolive, that wide-ranging print advertisement campaigns were rolled out in the Chinese and English language newspapers of China from 1917 onwards. The advertisements focused on two distinct target audiences. One type appealed to the married woman, the mother, who it proclaims enjoys using soap for its cleansing power while nourishing the skin. Another targeted a different market segment, the unmarried young woman, which emphasizes its advantages for attracting eligible suitors – professional men in western suits – for the modern girl, who welcomes a soap based on scientific testing (the "test tube motif").

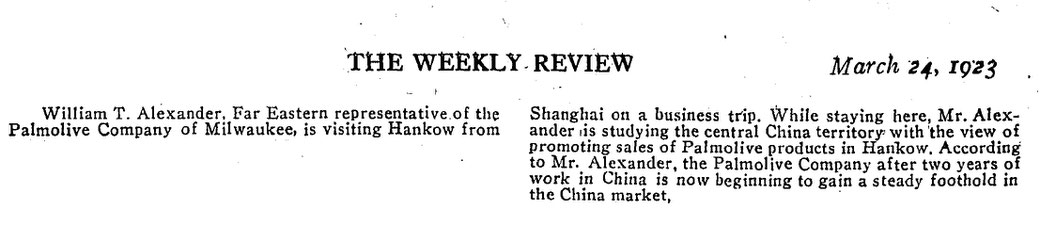

Initially, Palmolive’s distributor was Andersen & Meyer, then shortly after its sole agent for China became the American Trading Company. It chose “Zōnglǎn” (棕榄), a direct translation of the words palm and olive, as the trademarks Chinese brand name. In 1920 Palmolive established its first own China subsidiary on 49 Kiangse Rd. (todays Jiangxi Rd.) and one year later started to develop the market directly.

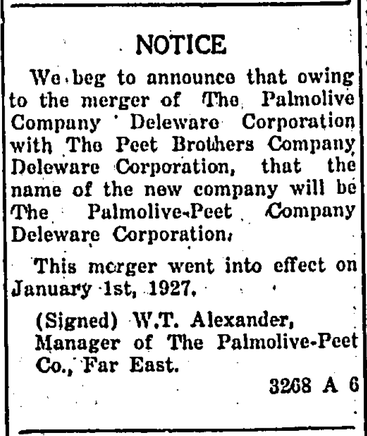

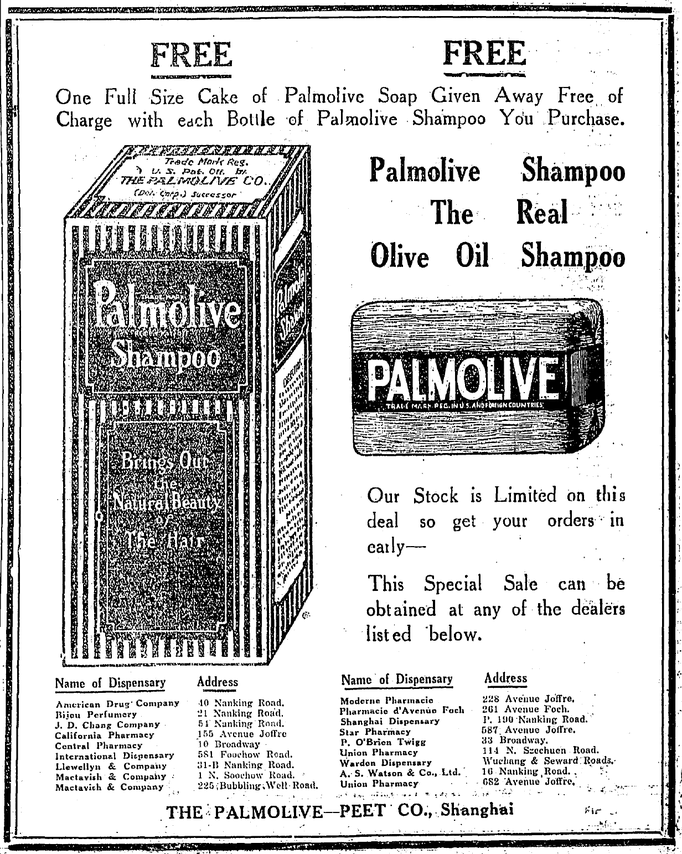

In 1926 Palmolive and the Peet Brothers Soap Company of Kansas City merged to become the Palmolive-Peet Company. In China the name change was formally announced on January 1st 1927 by William T. Alexander, the manager of the company in the Far-East.

Only one and a half years later in mid-1928, Palmolive-Peet announced a merger with Colgate Co. The new company was named the "Colgate Palmolive Peet Company” and combined the three oldest and largest soap and perfumery companies in the USA. Together it had seven US manufacturing facilities as well as factories in 14 foreign countries.

Since our advertising poster is titled “The Palmolive-Peet Co.” in its header (美国棕榄公司 in Chinese), which we now know only existed for approx. 1.5 years, we can undoubtedly date it to 1927. This timeframe also matches the hairstyle and dress of the pretty, smiling young woman depicted in the advertisement. She is surrounded by a frame and the interior setting of her home, which feature both traditional Chinese and Western art nouveau type design elements. Palmolive’s Vanishing Cream and Toilet Soap products are strategically scattered on the Western-style dressing table and are depicted and described in more detail in the poster’s footer.

The particular painting technique of our poster was popularized by the influential illustrator Zhèng Màntuó (郑曼陀) around 1915. It was known as rub-and-paint and involved rubbing carbon into paper and then overlaying it with light watercolor pigments. A closer look at the lower left corner of the poster, however reveals the artists signature to be Zhìyīng (樨英).

Háng Zhìyīng (杭樨英) was born on May 30th 1900 in Haining, Zhejiang Province. He loved painting since childhood and in 1913 moved to Shanghai with his father to study art. Possibly he first was enrolled at the Jesuit-run painting school for orphans, Tou-Se-We (today a highly recommended museum), but this is uncertain. What is certain is that Hang entered the Commercial Press art department school, where he trained with Chinese and foreign art teachers, receiving instruction in book design, commercial art, advertising design, and practical art, as well as in Chinese-style and Western-style painting. There Hang Zhiying managed to acquire the technique perfectionated by Zeng Mantuo and it subsequently became a standard method among many calendar poster artists.

In 1920 (or, according to some sources, 1922), Hang Zhiying left the Commercial Press to establish his own studio, specializing in advertisement posters and product package design. Zhiying Studio initially closely followed the style of Zheng Mantuo but eventually broke away from it, creating its own distinct and highly influential new style that led Chinese commercial art to its heyday. It is this “Shanghai style” that we today still associate the most with the famed 1930s calendar posters of enticing urban Chinese beauties. Iconic themes and paintings from Zhiying Studio for example include the famous “pipa girl”, “bicycle girl” or “motorcycle girl”.

It is estimated that Hang Zhiying’s studio annually produced over 200 advertising items and magazine covers per year, of which up to 80 were calendar posters and hangers. The studio at its peak employed up to 10 artists and ultimately was responsible for the majority of the total output of advertising posters in Republican China. It is estimated to have created up to 1600 individual designs over the time of its existence.

Besides Palmolive, the studios clients were among many others the Kwong Sang Hong company with their famous Two Girls Florida Water brand, the German Indanthrene dye by BASF, Eveready batteries, the Great Eastern Dispensary, Nestlé, Dr. Williams, British American Tobacco (BAT), Nanyang Brothers, My Dear cigarettes, and many more tobacco companies.

During the Sino-Japanese war, Hang Zhiying staunchly refused to work for the Japanese, leading to the eventual closure of his studio. It reopened again after the war in 1945 but sadly Hang Zhiying died at a young age on September 18, 1947 of a brain hemorrhage, apparently due to overwork. His contributions extended far beyond calendar poster paintings, as he left an indelible mark on Shanghai's commercial, fine arts, and advertising design fields throughout the 1920s to 1940s and beyond. Following the communist revolution, formerly commercial artists seamlessly transitioned to creating equally iconic propaganda posters, which continued to reflect the profound influence of Hang Zhiying's artistic legacy well into the 1970s.

P.S.: More on the history of Chinese advertising calendar posters in our previous article here, and more on the marketing of soap during Republican China here.

Write a comment