Happy Chinese New Year! This rare A.S. Watsons advertisement from our collection not only has a peculiar design around the auspicious character 康 (health), but tells the origin story and evolution of the famous Chinese calendar posters which were in fact pioneered by Watsons in the 1880s together with a second British firm.

A.S. Watson & Co (屈臣氏药房) is the oldest retailer still in existence in China. Its roots date back to the Canton Dispensary opened in 1828 in Guangdong. It moved to Hong Kong in 1841 and in 1843 was renamed the Hong Kong Dispensary. In 1856, the company appointed Dr J. Llewellyn, to move to Shanghai to operate a branch of the Dispensary. It was later renamed to “Shanghai Pharmacy” under the management of SW Cleave.

The British pharmacist Alexander Skirving Watson joined the business as manager in 1858 and worked his way up to ultimately, in 1871, having the dispensary change its name to A. S. Watson & Company (ASW).

The company went public on January 16, 1886 and the raised capital was among others used to relocate the Shanghai branch of the Dispensary to larger premises on the Bund as well as erect a soda water manufacturing plant, located at 321 Kiangse (Jiangxi) Road. As part of the business expansion and professionalization, Watson’s trademarked its wide range of private label brands, laying the groundwork for expanding its marketing activities. This takes us to the medium of advertising calendar posters which Watson’s would soon help establish and popularize in China.

Printed calendars for the purpose of advertising were first created in the United States in the middle of the 19th century and quickly became one of the most popular promotional devices. One of the first known early advertisement calendars, for the year 1863, was lithographed by Ehrgott, Forbriger & Co. Lith. of Cincinnati.

By the 1870s the newly developed techniques of chromolithography allowed for the printing of brilliantly colored images and opened the doors to even more vigorous advertising.

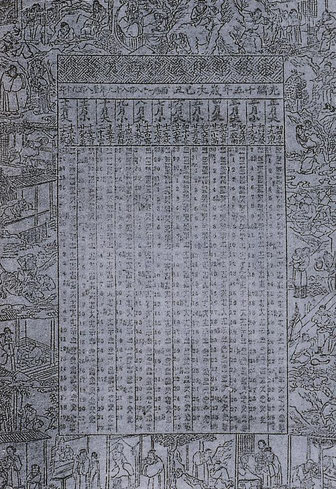

In contrast, printed calendars in China evolved much earlier and in a distinct fashion. After all woodblock printing was invented in China already during the Tang dynasty (618 to 907 AD). So called nianhua (年画), meaning “New Year’s pictures”, were printed in the form of door god banners that were attached to the entrances of homes. By the eighteenth-century hundreds of thousands of inexpensive single-sheet prints were mass-produced every year by print shops in almost every province of the empire, but most notably from the celebrated Yangliuqing near Tianjin, in the north, to the famous Taohuawu in Suzhou, in the south.

It was around that time that the door gods were joined by other household protective and auspicious deities, particularly in the form of pictorial calendars, of which there were three categories:

One is associated with the image of the Kitchen God, the most important of a plethora of Chinese domestic gods that protect the hearth and family.

A second popular theme was the “Welcoming Joy” picture calendars, which were printed at the celebrated Taohuawu area in Suzhou. One of the earliest examples is dated to 1766.

The last type of woodblock printer calendars was the Spring Ox Calendar, a single sheet pictorial almanac illustrating events associated with Spring ploughing ceremony. An early Spring Ox calendar, dated 1843, was also printed in Suzhou.

It had become a custom to gift any of these three types of calendars for Chinese New Year, primarily by merchants to their most valued customers.

After the First Opium War in 1842, Western traders populated Hong Kong and the Chinese treaty ports, established publishing houses and newspapers and soon began to blend the Chinese and Western traditions of print calendars. The earliest known example of such a calendar poster is the Anglo-Chinese calendar for 1854 printed in Hong Kong by the newspaper China Mail. The central field juxtaposes the Gregorian calendar with the Chinese lunar calendar and displays practical information pertinent to trade and commerce: the arrival and departure schedules of mail steamers and exchange rates. The calendar though does not feature any illustrations nor design elements except for a delicate filigree border as a decorative flourish.

The next known example is from 1876, when an advertisement for a “Chinese English calendar poster” appeared in the Shanghai newspaper, Shenbao. The ad represents the first known use of “yuefenpai.” (月份牌), the Chinese term for calendar posters still used today. Unfortunately, only the advertisement but no known copy of the actual calendar has survived.

The 1880s were a pivotal decade in the history of Chinese calendar posters.

On the one hand the earliest extant yuefenpai printed in Shanghai was a lithographed gift calendar for the year 1889, published by Shenbao. Shanghai was a latecomer to the woodblock print enterprise and was an offshoot of the nearby famous Suzhou print industry.

But as Shanghai became the commercial heart of China, it finally also developed all the prerequisites for a flourishing modern art center: a thriving international trade, a solid financial footing, a prosperous printing industry, and a population of artists eager to make a living.

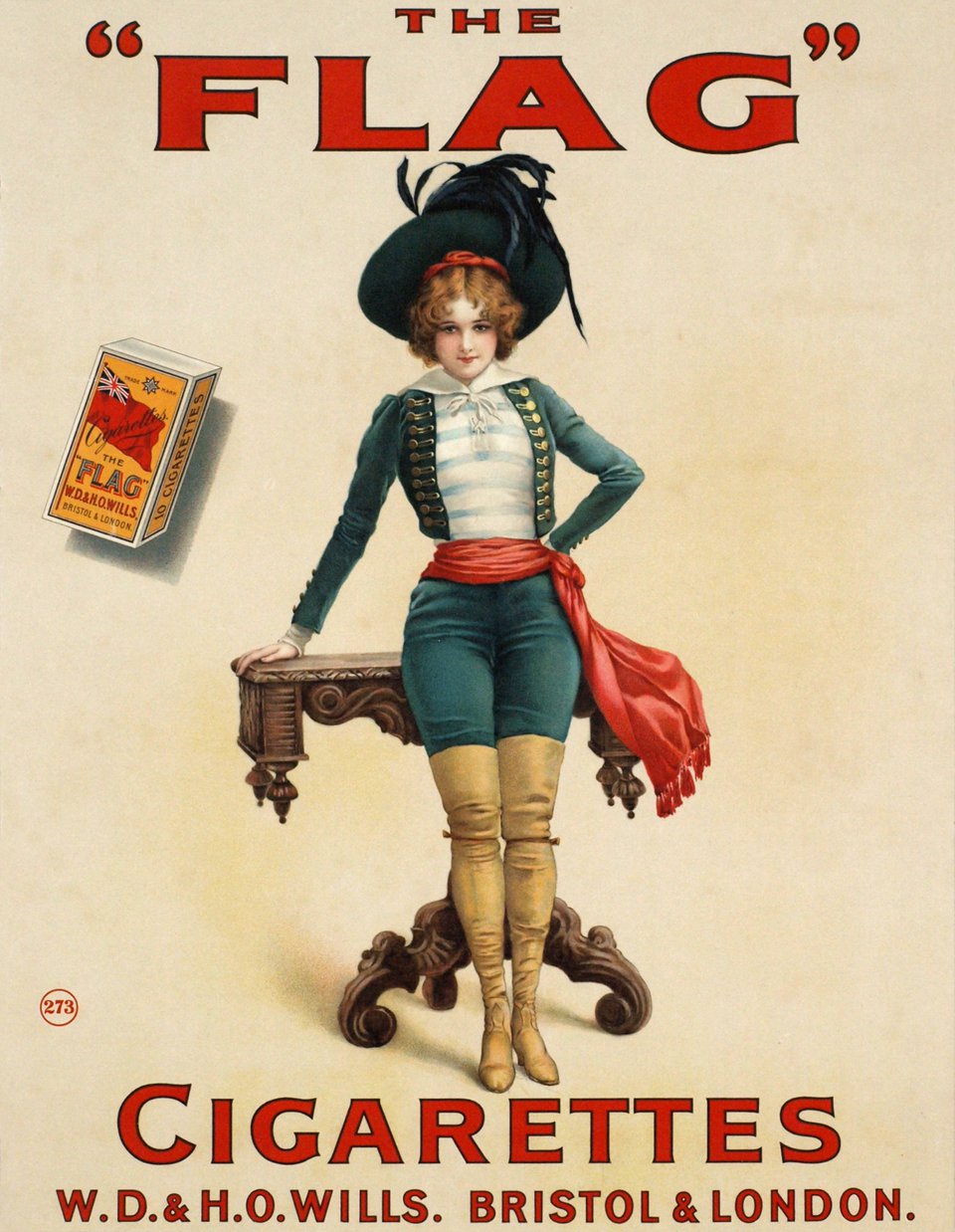

It is important to note that up to the 1870s none of the mentioned calendars were actually created for the purpose of advertising. They did not contain any depictions of products, logos nor brand names. Equally important to keep in mind, is that for regular advertising posters in China Western companies blithely ignored Chinese preferences in favor of Western motifs: Cigarette cards bore illustrations to German fairy tales, posters pictured American landscapes and American heroes like George Washington and Abraham Lincoln, and even buxom European women with décolleté necklines, none of which carried any meaning for Chinese consumers.

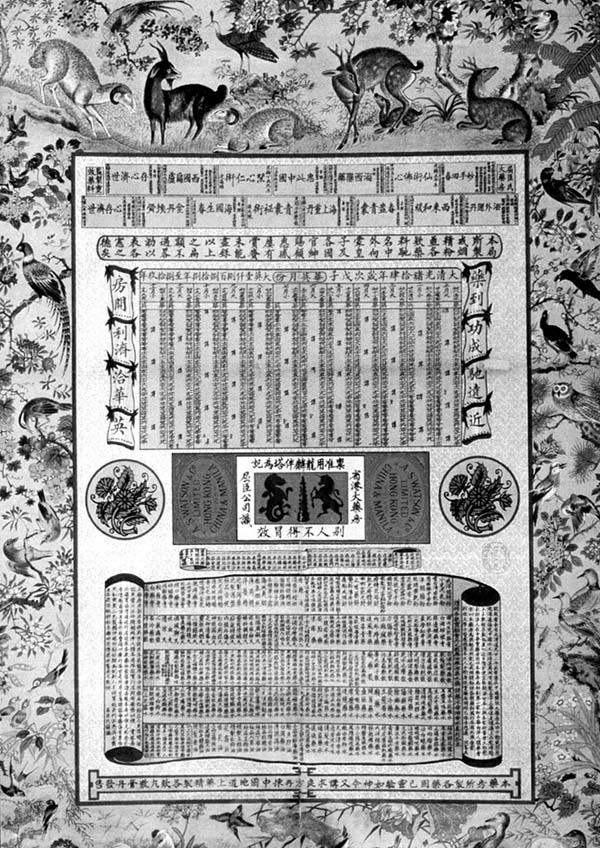

This all changed in 1884 when A.S. Watsons created a groundbreaking poster that actually combined a calendar with commercial advertising and Chinese motifs.

It is titled "Chinese English Calendar" for the year 1885 and the firm’s logo is prominently featured in the center of the poster. Below rich descriptions of A.S. Watson’s products can be found. The borders are filled with colorful animals that carry felicitous connotations in Chinese culture. Deer, cranes, and pine trees for example are all symbols of longevity.

The design and layout seemed to have been very well received by business partners and consumers alike as it was continued in following years. Another known surviving version exists for the year 1889.

A second pivotal calendar poster published in 1888 for the year 1889 was the “Chinese Almanac” by the rubber and tea growers and importers, Thomas Barlow and Brother Co. The calendar itself is printed on an open scroll at the bottom and is labeled “Chinese and English Calendars Combined”. On the top left it displays the logo and the Chinese “Hong” trading name of the firm, while the rest of the poster is filled with a multitude of small motifs derived from Indian, English, and Chinese contexts: exquisitely rendered animals, birds, human figures and auspicious symbols. It was designed by Dianshizhai Pictorial staff artist Zhang Zhiying (張志瀛). Born in Wuxi and trained in Suzhou, he was the earliest-known Chinese calendar artist and highly influential to generations of illustrators after him.

While Barlow & Company remained a comparatively small enterprise, the auspicious calendar poster of A.S. Watson indeed brought longevity and wealth to not only its recipients but also its publisher: By 1895 the company operated 35 stores in China and produced 300 dispensary, toiletry and perfumery lines.

Watsons continued the tradition of auspicious Chinese symbolism in posters and in 1907 started to issue an innovative new design of annual calendars that boasted large-scale auspicious characters, such as those for “wealth,”, “prosperity”, “longevity,” and “enjoyment”.

Just like in the 1916 edition from our collection the character for health’s thick strokes were filled with figures of the Eight Immortals, the “Eighteen Lohan,” the elephant and boy from the traditional calendar’s visual idiom, or other auspicious motifs.

The illustrations are attributed to the well-known figure painter Feng Runzhi (1852 – 1937) from Guangdong.

The striking design, characterized by the central cut-out in the shape of a Chinese character, was, alas, not as original as it seemed, as it was in fact a replication of an earlier print that had been produced in Taohuawu, Suzhou at the close of the 19th century.

The original poster features a character for longevity filled with small figures of the Queen Mother of the West at the top, the “Three Stars” of good fortune, wealth, and longevity in the center and the Eight Immortals in the lower part.

Neither the first nor last time that advertising borrowed from art…

After running the auspicious character theme on its poster for close to 20 years, Watsons discontinued the legendary design in 1926 at the dawn of a new area: Popular folklore and auspicious symbols gave way for pretty girls in alluring qipaos targeted at the growing urban middle class. It is these iconic “Modern Girls” advertisements from the 1920s and 30s that Chinese calendar posters are still associated with today but lest we forget their origins and that they are a quintessential embodiment of the harmonious melding of the ancient and the contemporary, the traditional and the avant-garde, the Oriental and the Occidental, all along the fine line of cultural exchange, art and commercialism.

A.S. Watson, like no other foreign-founded enterprise in China, mastered all of the above and after the 1920s once again was blessed with good fortune and a long life. By 1941 Watson’s was already the largest chemist, retailer of health and beauty products, dealer in wines and spirits, and manufacturer of aerated water in Asia.

Today A.S. Watson Group is the world's largest international health and beauty retailer, with over 16,000 stores in 27 markets worldwide serving over 5.3 billion customers every year.

P.S.: A large portion of this analysis was derived and copied verbatim from the seminal work, "Selling Happiness" by Ellen Johnston Laing, which is widely regarded as the premier authority on the historical and cultural significance of Chinese calendar posters and commercial art. A big thank you also to Yun Xie for the photograph and source of the excellent 1885 A.S. Watsons calendar poster.

Write a comment