As gorgeous and innocent looking this “Honey Soap” advertising poster featuring Chinese actress Li Lili is, it actually tells the story of several dark episodes from China’s marketing and entertainment history.

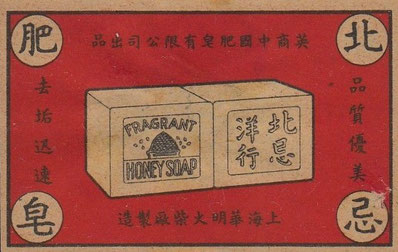

To understand why we have to start from the very beginning: The idea of honey soap has its roots with Englishman William Hesketh Lever. Beginning in 1874, Lever’s wholesale grocery business had been marketing a soap called “Lever’s Pure Honey”. His main competitor William Gossage & Sons produced two similar products called “Fragrant Honey Soap” and “Family Honey Soap”. In 1919 Lever Brothers acquired Gossage but all of their respective brands continued to be advertised & sold.

Besides cigarettes and petroleum, soap was one of the largest and most rapidly developing consumer packaged goods (CPG) categories in China and was dominated by Western manufacturers incl. aforementioned British Lever Bros, Gossage’s and the American Procter & Gamble or B.J. Johnson’s Palmolive.

But with the tremendous opportunity also arose increasing competition. On the one hand, the Western soap brands were plagued by local Chinese manufacturers, most of which produced cheaper and lower quality counterfeits or knock-off brands. In 1909 for example, the North China Daily Herald reports of a court case in which a certain Lu Yunsheng was charged with producing imitations of Gossage’s honey soap including their well-known and trademarked beehive logo.

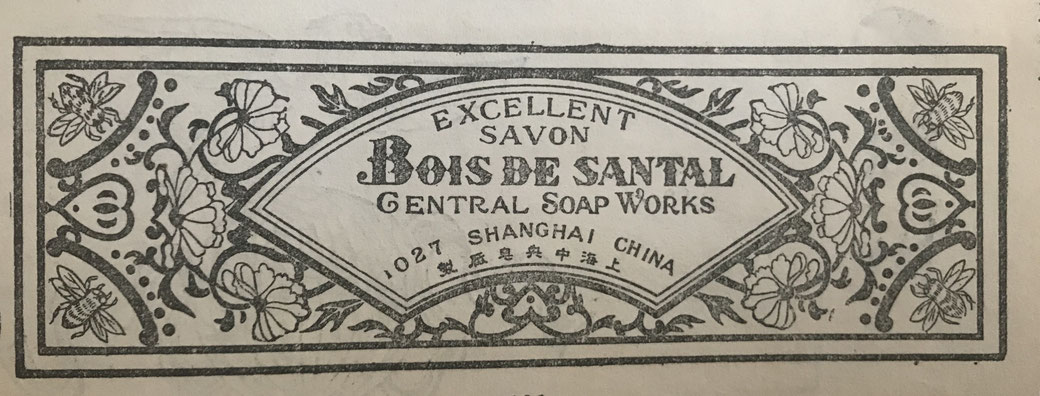

In 1919 the Shanghai Gazette writes of yet another legal dispute in which William Gossage & Son’s sued the Heng Li Soap Factory for producing forgeries of their Fragrant Honey Soap. By the 1930s one of the most notorious Chinese copy-cat producers was the Central Soap Works (中央香皂厂), which for example in 1931 was brought to court by the Colgate-Palmolive-Peet company for “copying the wrapping, dress-up, and designs, as well as the impressions on cakes of toilet soaps manufactured by the complainants, and in particular, such relating to the well-known soap called Palmolive”. In 1935 we find a similar trademark dispute against Central Soap Works by Unilever in regards to their Lever’s Health Soap.

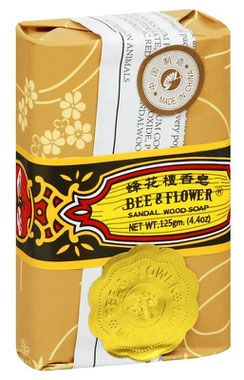

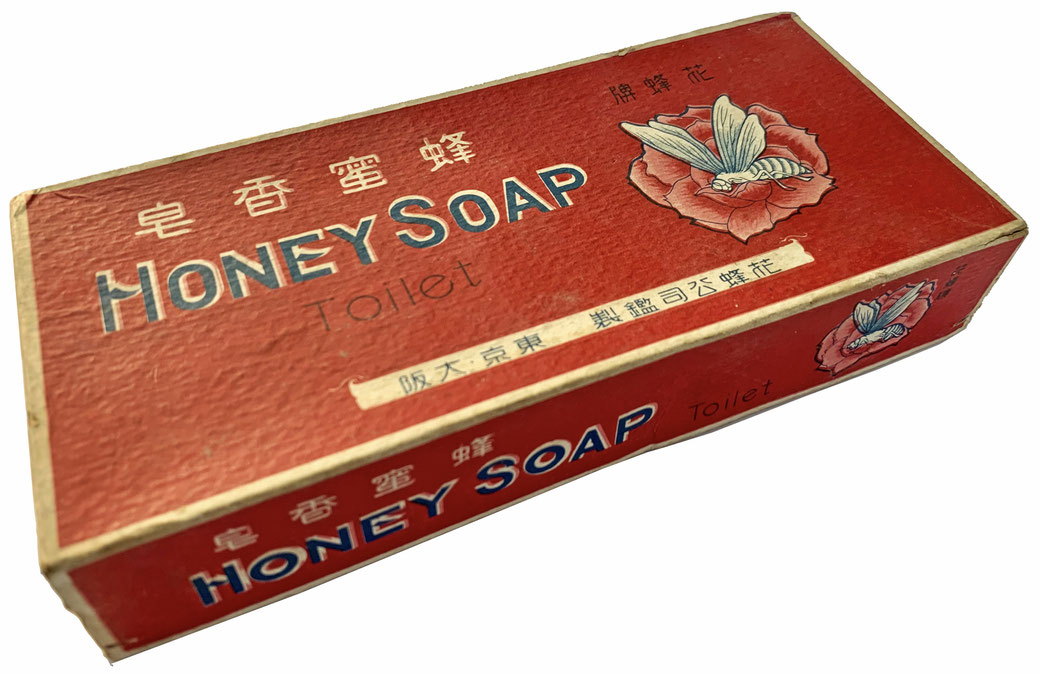

In 1928 Central Soap Works was also the one to copy the concept and design of the Sandalwood Soap (“Savon Bois de Santal”) created by French producers Roger & Gallet in 1895. Their Chinese knock-off trademark was registered as “Excellent Savon Bois de Santal” in English, while the Chinese term was “Bee & Flower brand” (蜂花牌). It’s packaging looked almost identical to the French original, but additionally had honey bees added to its four corners. Central Soap Works somehow managed to get away with most of its countless imitations and survived until the Communist Revolution after which it was merged with Unilever’s old Shanghai factory and nationalized. Their knock-off brand still exists today and is now called Bee & Flower Sandalwood Soap (蜂花檀香皂). It still features same label design imitated after Roger & Gallet’s original and is proudly sold globally by the Shanghai Soap Co. Ltd. “since 1928”.

But back to Qing Dynasty and Republican China, where it was not only Chinese manufacturers which Western soap brands had to compete with: Since the Treaty of Shimonoseki signed in 1895, Japanese producers and trading firms had been permitted to operate ships on the Yangtze River, establish manufacturing factories in treaty ports and open additional four more ports to foreign trade. Notable soap manufacturers from the Land of the Rising Sun which soon penetrated the Chinese market with their brands, were e.g. the Kao Soap Company, the Cow Brand Soap Company or the Harumoto Soap Factory.

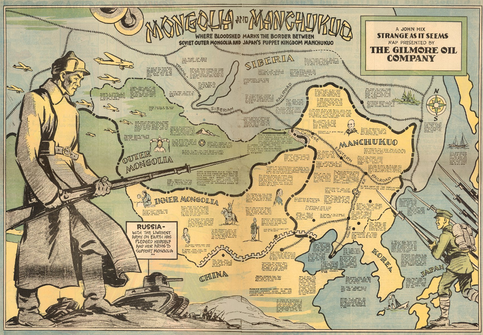

In 1931 Japan invaded Manchuria and transformed it into the puppet state of Manchukuo the following year. There the colonial government organized and implemented two five-year plans with rapid industrial development as a primary goal. The aggressive Japanese investment led to Manchukuo's emergence as the third-largest industrial area in East Asia (after Japan-proper and the U.S.S.R.). The country imposed tariffs on the import of booming categories such as Western-manufactured cigarettes or soaps, while at the same time its own, newly developed manufacturing powerhouses opened offices, branches, factories and joint-stock companies in mainland China, and heavily invested in advertising for its brands.

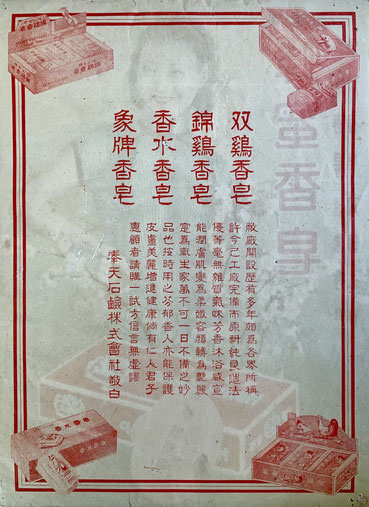

This now takes us to the time of our “Honey Soap” (蜂蜜香皂) advertising poster. It’s English brand name obviously was inspired by Lever’s or Gossages honey soaps, while its Chinese brand term Huā fēng pái (花蜂牌) translates to Flower & Bee brand – a simple inversion of Central Soap Works’ Bee & Flower brand, its logo featuring the proverbial flower and bee. A fascinating exhibit of a copy of a copy and its provenance tracked from British manufacturers, to Chinese counterfeiters and on to a pervasive Japanese propaganda knock-off. The culprit behind this stunt is revealed on the backside of the poster as the Hoten Soap Co. Ltd. (奉天石鹼株式會社) from the Manchukuoan city of Mukden (today’s Shenyang). In the late 1930’s the company was purchased by the powerful Japanese conglomerate Nippon Oil & Fat Co. (日本油脂株式会社) who aggressively increased its production and ruthlessly stepped up its branding and advertising game as exemplified by our poster. Besides “Honey Soap” it also promoted several other copy-cat brands on the backside of the poster such as “Golden Pheasant Toilet Soap” (锦鸡香皂), a knock-off of the China Chemical Works Ltd.’s brand of the same name, or “Elephant Brand Soap” (象牌香皂) who's Chinese name is strongly reminiscent of Procter & Gamble’s flagship brand “Ivory Soap” (象牙牌香皂) developed in 1879.

But the brazenness and political abuse of consumer brands by Nippon Oil & Fat Co. did not end there. What tops off the audacity of the advertisement poster is the display of a certain Chinese celebrity as apparent spokesperson for the brand: Li Lili (黎莉莉) was one of the most popular Chinese film actresses of the time and referred to as “China’s Mae West”. She was famous for portraying the “happy go lucky girl” prototype in her roles. Like many of her contemporaries from the Hollywood of the East, she had a lucrative endorsement deal with Unilever’s Lux soap and alone because of that would not have promoted any other soap brand.

However based on her family background and movie career it can be ruled out without a doubt that she would have ever advertised a Japanese brand: Her movies Playthings (1933), The Great Road (1934) and Storm on the Border (1940) were blockbusters and all part of the so called Chinese National Defense Cinema – patriotic and expressedly anti-Japanese. Not only that, but Li’s father, Qian Zhuangfei, was in fact a secret agent and one of the early heroes of the Chinese Communist Party, which recently named him one of the 50 most important people in the country's history.

After war with Japan broke out in 1937, Li Lili joined the China Film Studio in Chungking, China's wartime capital, where she continued to act in Chinese movie productions.

Our poster thus is a prime example of misleading consumer advertising used as a political tool by Imperial Japan. The Japanese company Nippon Oil & Fat Co. blatantly copied one of Li Lili’s promo photos onto their advertising, to make Manchukuoan and Chinese consumers believe that the famous and once-patriotic actress had switched sides and became a literal Manchurian candidate of brand ambassadorship for a Japanese vassal state brand.

It is not known if Li Lili was aware of “Honey Soaps” illegitimate use of her picture, but unfortunately the tragedy of her career because of loyalty to Party & country did not end there: During the Cultural Revolution, Li and her husband were denounced and tortured on the personal orders of Mao's wife Jiang Qing: Li had acted with the later “Madame Mao”, and outshone her, in films such as Blood on Wolf Mountain. Li’s husband died but she survived and lived to be 90, having passed away in 2005. She was the last living Chinese movie star from the silent film era and most certainly also the last living advertising beauty of Old China – even if unknowingly.

Write a comment

HandsomeMan (Tuesday, 03 January 2023 19:50)

What a great story thank you so much for illuminating it.

Reminds me of how the Japanese had mixed opium into cigarettes to make them super-addictive and hooked a massive part of the population in Manchuria into opium addiction, all to finance its war effort. Industrial scale evil.