Novartis is one of world’s largest pharma corporations and was formed in 1996 by the merger of Ciba-Geigy & Sandoz – originally three independent businesses all from the same small town of Basel, which is strategically located in Switzerland on the border to France and Germany. The surprisingly progressive 1929 calendar poster advertisement from our collection was produced for the most successful of these companies in China…

Geigy was the oldest of the three and dates back to 1758, when Johann Rudolf Geigy set up shop in Basel as a chemist and druggist. His heirs branched into dyes for the textile industry and eventually took the company public in 1901. In the 1930s and ’40s the business expanded to agricultural chemicals and pharmaceuticals. It is most well-known today for one of its researchers, Paul Müller, who won a Nobel Prize in 1948 for discovering the insecticidal properties of DDT.

Sandoz AG originated in 1886, when Alfred Kern and Edouard Sandoz founded a firm – also in Basel - to manufacture synthetic dyes. The business grew rapidly, and in 1895, the year it began making pharmaceuticals, it was transformed into a joint-stock company. In the 1920s and ’30s it started producing cleaning agents and other household products. Just like Geigy, Sandoz is famous for a groundbreaking chemical discovery: In 1938 one of its researchers, Albert Hofmann, first synthesized LSD.

Finally, CIBA developed from a silk-dyeing business owned by Alexander Clavel, who began manufacturing the synthetic dye fuchsine in 1859. In 1884 the firm was transformed into an LLC called the Gesellschaft für Chemische Industrie Basel (“Society of Chemical Industry in Basle”), with its last words forming the acronym CIBA. In addition to dyes, CIBA became known for pharmaceuticals, which it began producing in 1900. By then it had emerged as the largest chemical company in Switzerland.

Already since the 1870s, Geigy, Sandoz and CIBA dyestuffs were exported to the Far East. They lit up the shops of Vadgadi, Bombay (now Mumbai) and Armenian Street in Calcutta (now Kolkata), and the bazaars of Kobe and Shanghai.

In China, Geigy seems to have been only formally registered as a brand in 1926, and was localized as Jiājī yánliào (嘉基顏料).

Advertisements and product lists from our collection as well as print ads in the newspaper archives only show an increased activity in the late 1940s after WWII in 1945.

Sandoz on the other hand, under representation of the largest German trading firm Carlowitz & Co., was introduced to Chinese buyers as Shāndéshì (山德士) and already started newspaper advertisements in the early 1920s.

In 1930 the company noticeably increased its marketing efforts in China with regular adverts for its calcium gluconate product.

A Chinese subsidiary was soon established and first listed in the 1932 Hong list – the primary business directory of foreign firms in China at the time.

Persistent ad campaigns ran until 1936, resumed again in 1938 and ‘39 and the Swiss company continued to advertise throughout WWII in the 1940s.

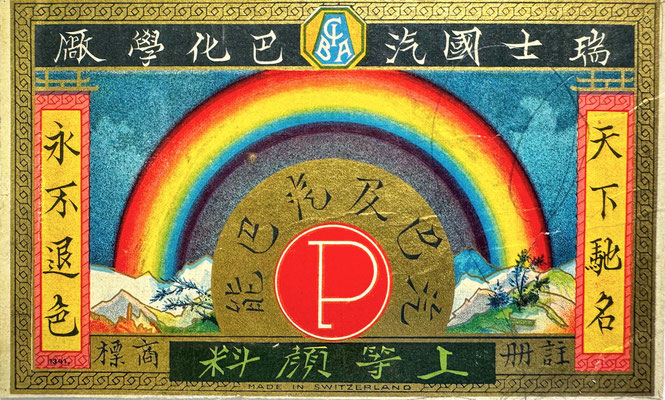

A book of textile dye samples and a gorgeous trademark label from that time are preserved in our collection, with shining bright colors to this day!

But now on to CIBA, which was the most active member of the thriving Basel chemical industry around the world and in China alike. Already in 1913 it was listed in the Hong List under its original name “Society of Chemical Industry in Basle”.

It was represented by a vast distribution network of three independent German trading firms across China, Slevogt & Co. in Shanghai, Siemssen & Co in Tianjin, Hankou (Wuhan) and Guangzhou and Pasedag & Co. in Xiamen.

The distributors lost no time for CIBA to make a name for itself in China. Countless newspaper ads were published for CIBA throughout the year 1914 for e.g. Phytin, a medicine to improve physical weakness, anemia, blood circulation, and nerve strength, its derivatives Quinin Phytin and Fortossan as well as the wound healing cream Salenal.

Already then, a fitting Chinese name for the company was introduced with Qìbā (汽巴) that remained in use until 2009, when Ciba Specialty Chemicals as acquired by German chemical giant BASF and the brand was retired.

Meanwhile back in Switzerland CIBA initiated intense research of sex hormones in 1914 and over the next years developed eight gonadal and hormonal products such as Agomensin, Sistomensin and Prokliman. This new line of pharmaceuticals peaked (pun intended) in 1931, with Androstin – a testicular extract engineered to target “climacterium virile”, or in other words, impotence. This was the earliest commercially available form of HRT (hormone replacement therapy) produced by a reputable company.

The First World War tremendously benefitted Swiss companies globally, since the country remained neutral throughout the conflict. CIBA made the strongest gains in absolute terms but in relative terms, Sandoz was the biggest winner: its turnover rose from 6 million Swiss francs in 1914 to 37 million in the last two years of the war – a stunning six-fold increase. In China CIBA’s distributors however were all German firms and at the latest in 1917 German businesses were seized and its citizens interned or forced to repatriate, which undoubtedly also affected its Swiss clients.

After, the war in 1918, CIBA, Geigy and Sandoz joined to form a chemical industry cartel, the Interessengemeinschaft Basel (“Basel Syndicate”), or Basel IG, in order to compete with the infamous German chemical cartel IG Farben.

Propelled by its record profits from the wartime, the Basel Syndicate founded further foreign subsidiaries and set up new production sites in Europe, the USA, South America, Japan and - China.

Especially CIBA acted quickly: already in 1918, according to the London Gazette, it was up and running again in Shanghai under new and even more experienced leadership, personified by the Swiss merchant Mr. Jean (John) R.A. Merian. Not much is known about Merian, but he undoubtedly was instrumental to CIBA’s success in China for well over the next decade. Merian is a renowned patrician family name in Basel and its almost certainly where John stemmed from.

He might however have also been the Johann Rudolph Merian, born on October 26th 1888 in Yokohama to Johann Rudolf (sic) Merian. Johann Merian the elder came to Japan in 1874 to join a Swiss trading firm, of which he eventually became the sole owner and renamed it to J.R. Merian & Co.

The company maintained close contacts to CIBA and Geigy, who since the 1870's delivered dye stuffs to Japan through representatives.

Be it as it may, Merian as an independent contractor not only restarted CIBA’s business in China but professionally expanded it in terms of sales, distribution and advertising.

From 1919 onwards and throughout the 1920s, CIBA ran massive print campaigns, advertising industrial dyestuff as well as consumer-facing pharmaceutical products.

Over 1,300 newspaper ads found in the archives as well as artifacts from our collection such as dye color sample books, magazine advertisements, instruction leaflets and product catalogues are a testament to CIBA’s impactful marketing efforts at the time.

It was also under J. Merian’s representation that CIBA started to publish its first Chinese customer magazine, the “CIBA Quarterly”.

When in 1928, the Nationalist government led by Chiang Kai-shek established its capital in Nanjing and initiated significant reforms such as the creation of a centralized Chinese trademark registry, Merian made sure to have all of CIBA’s relevant brand rights secured there.

Another important advertising tool that John Merian built on and further developed for CIBA, were so called “trademark labels” - beautiful chromolithographs with the brands name and localized imagery full of Eastern symbolism. As early as the 1880s, dyestuffs came on to the Asian markets in such complete packaging, consisting of a main label, a spine label and a suitable seal-like closure –all carefully bonded to a glossy paper envelope that often showed the color of the product inside. A travel report from 1885 stressed that the Chinese attached less importance to the purity of the dyestuffs than to the careful crafting of the labels. The images of flowers and birds destined for Shanghai reveal both knowledge of Chinese painting and a distinctly European formal language. From the end of the 19th century onward, CIBA, Sandoz and Geigy contributed to an important economic and cultural exchange by building a bridge between primarily Swiss artists and Asian customers.

Ca. 1920s & 1930s CIBA Chinese trademark labels. From the MOFBA collection.

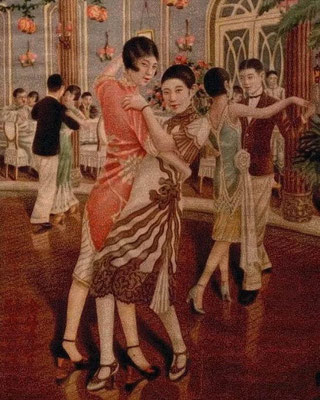

By the middle of the Roaring Twenties, Shanghai had transformed into one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world, where colonial enclaves, neon-lit dance halls, and bustling trade routes collided. Dubbed the “Paris of the East,” the city pulsed with jazz music imported by African American musicians and Western expatriates, shaping not just nightlife but also fashion, attitude, and identity.

The rise of the “modern girl” — urban, stylish, independent — embodied this cultural fusion, blending Chinese elegance with Western flair.

Our 1929 calendar poster perfectly reflects that world and Merian’s understanding of how to navigate it on behalf of CIBA: In its center, a poised woman with an ultra-short and slick jazz-age bob, with a defined wave on the side, mimicking the popular “Eton crop”— a controversial style influenced by the Western flapper style. Her fashion — a luxurious blend of Art Deco and Chinese motifs — mirrors the era’s stylistic hybridity. Rather than spotlighting the product, the calendar sold a lifestyle of modernity and aspiration, suggesting that beauty, sophistication, and global modernism were now within reach — and all centered in Shanghai, the glittering crossroad of East and West. Well played for a small-town and conservative Swiss industrial company!

The footer of the poster shows dyestuff barrels on the right, a romanticized illustration of CIBA’s factory in Switzerland as well as on the left a reference to the previously mentioned trademark labels.

CIBA Shanghai offices in the 1930s.

Not only did Merian perfectly time his arrival in Shanghai for what would become the city’s cultural peak decade of the century, but also his departure. In April 1931, the North-China Sunday News announced that Mr. John R.A. Merian was “leaving for Switzerland after 13 years with the Society of Chemical Industry in Basle”.

The successor in his firm was Merians former employee W.E. Thommen, but less than one year later, in January of 1932, heavy fighting broke out in Shanghai between Japanese and Chinese troops and the boomtown on the Yangtze came to an abrupt stop for over a month.

CIBA China print ads & other ephemera. From the MOFBA collecton.

CIBA’s business eventually restarted but by 1935 was no longer under Merian’s representation and instead incorporated its own China entity called Ciba (China), Ld. under the management of S.G. Mills. Despite Switzerland continuing to be neutral and able to operate in China throughout the next decade, CIBA was heavily affected by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937 and later WWII.

Globally CIBA’s sales during that period fell below the figures of the 1930s.

After the establishment of the PRC in 1949 foreign companies withdrew from the country. In 1970 Ciba AG and J.R. Geigy SA merged to form Ciba-Geigy and following China's economic reforms, both Sandoz and them were among the first wave of Western pharma companies to re-establish a presence in the market during the early 1980s.

Since then, the combined entity that is now Novartis, has obtained nearly 90 new drug approvals in China, employs over 8,000 people on the ground and the country has become its second-largest market globally.

CIBA "Materia Medica" product catalog ca. 1930s. From the MOFBA collection.

Parts of this blog post and all numbered photos are taken from the document "25 years of Novartis – more than 250 years of innovation"

Write a comment