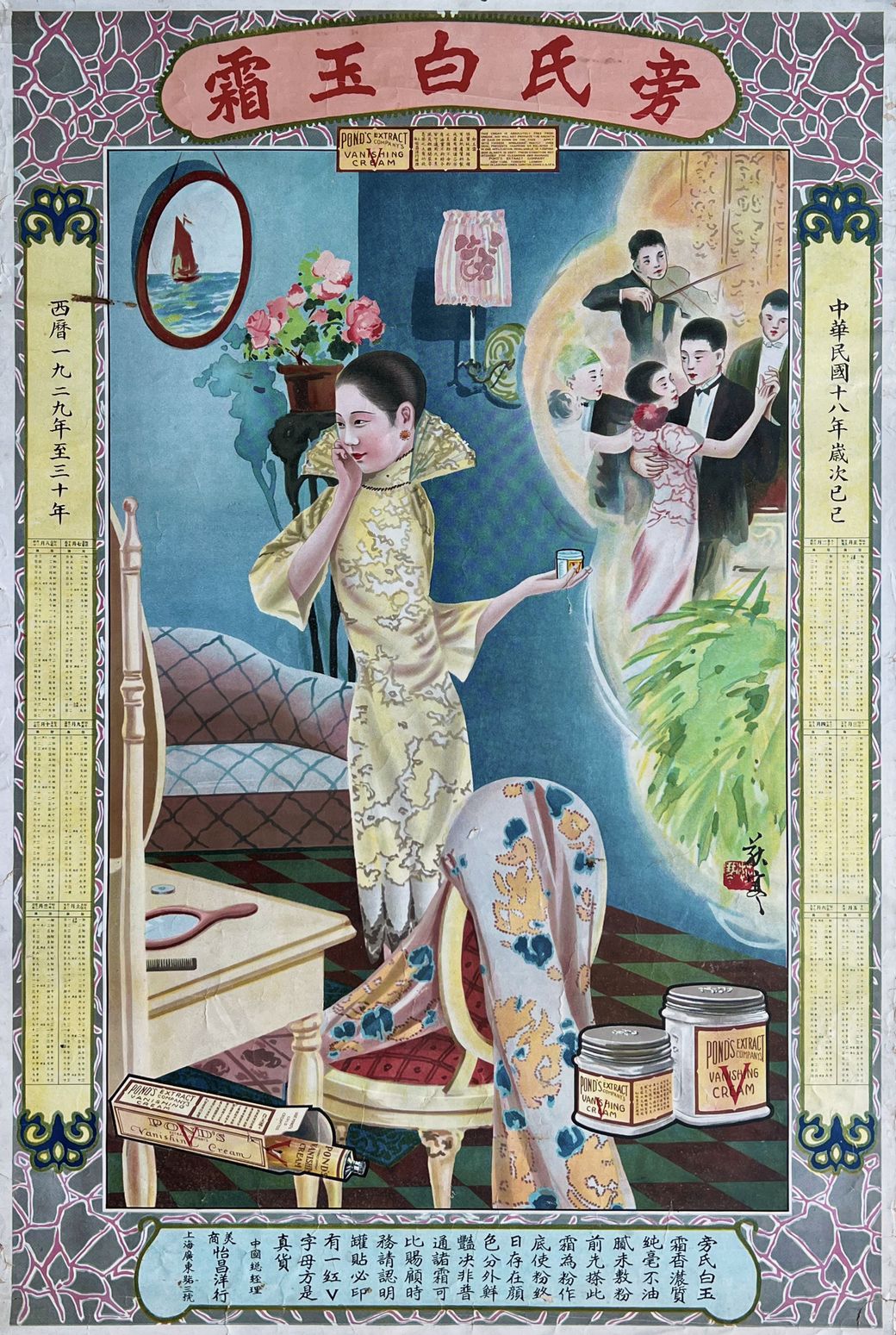

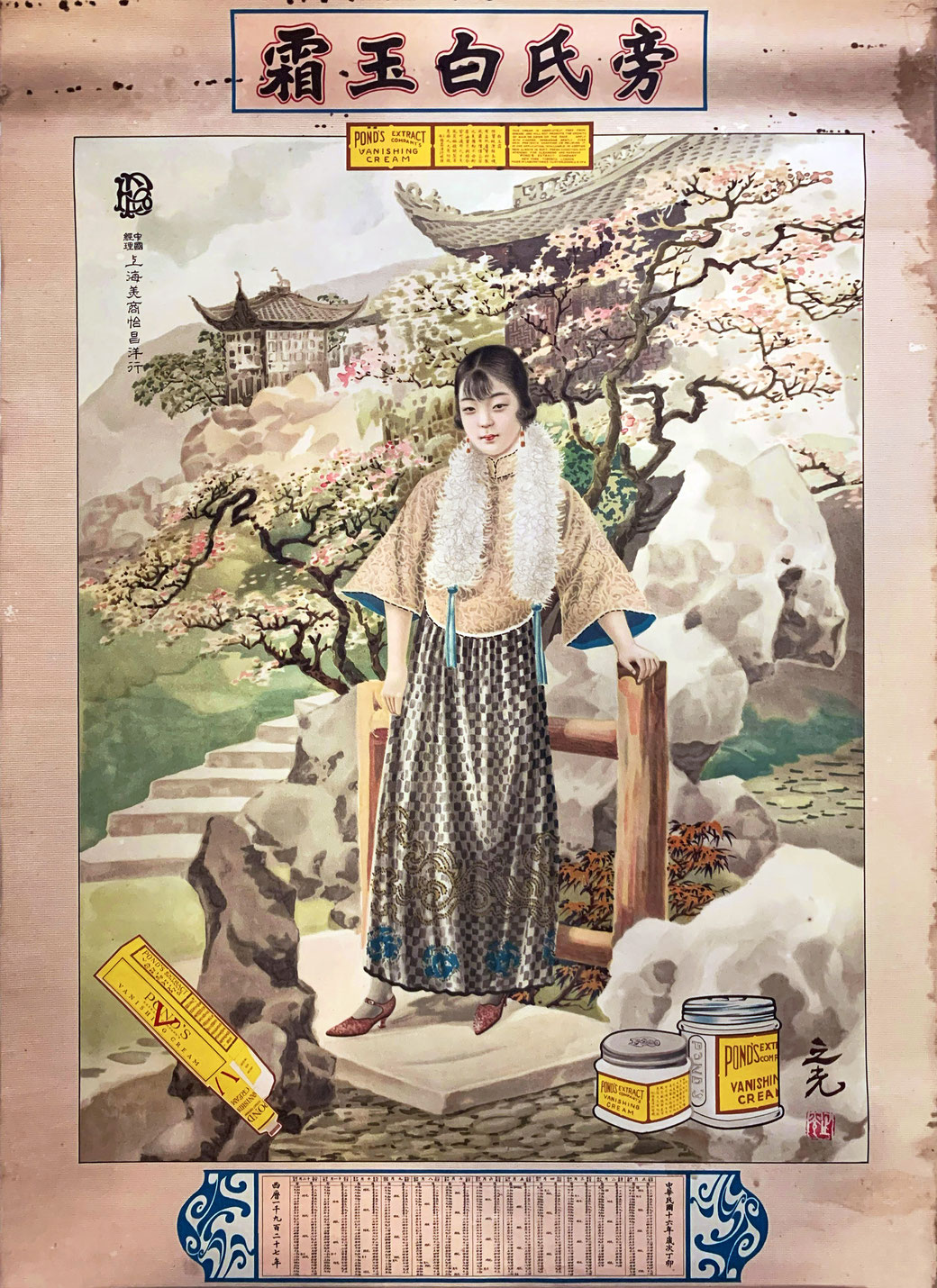

This 1929 Pond’s advertisement calendar is not only one of the most stunning pieces in our collection, but also an important artefact of China’s modern social history. The beauty brand and its ad agency, Carl Crow Inc., were instrumental in creating the archetypal “Modern Girl” whose image prevails in Chinese popular and commercial culture to this day. Here is the back story of what made it so iconic.

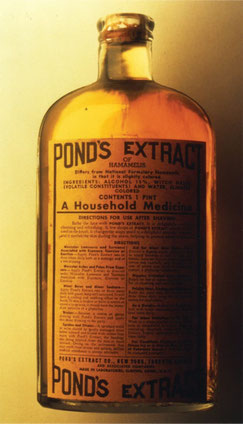

In 1846 American pharmacist Theron T. Pond from Utica, New York, invented the ‘Golden Treasure’ - a healing tea extracted from witch hazel, which he discovered could strengthen skin below the surface, helping it repair itself from small cuts and numerous other ailments. Soon after, the product became widely popular as the Pond's Extract.

This set the stage for what was to become the world’s first skincare brand, and a unique history of breakthroughs all dedicated to helping women keep their skin looking radiant and feeling soft. In the 1880s, several new witch hazel-based preparations were added to the company’s product line including an ointment, a soap, and for the first time a face cream.

In 1904, Pond’s introduced the iconic Pond’s Vanishing Cream, a category-defining term coined by the company, and followed this with Pond’s Cold Cream in 1905. A marketing campaign developed by the J. Walter Thompson advertising company in 1916, based on the idea that ‘Every skin needs two creams’, resulted in a threefold increase in sales and introduced the world to the first two-step skin care routine combining Pond’s Cold Cream with its Vanishing Cream. Pond's was also among the first companies to use celebrity endorsements in their advertising. Actresses like Constance Collier, Ruth Roland and Billie Burke were featured in Pond's ads, associating the brand with beauty and glamour as early as 1917.

Pond’s had already opened a London branch by 1878 but after the end of WWI and the success of its J. Walter Thompson campaign in the USA, rapidly moved into overseas markets, including the Far-East.

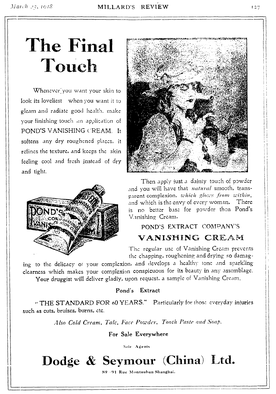

In early 1918 the American export firm Dodge & Seymour (怡昌洋行 ) in Shanghai was appointed sole agent for China.

That year, the first Chinese-language adverts for Pond’s in China’s largest newspaper, the Shenbao, were booked.

Also in March 1918, Pond’s first English-language advertisement appeared in Millard’ Review of the Far-East. This magazine was started by American newspaper pioneer Tom Millard just a year prior, after he sold his interest in the China Press, a newspaper he had founded in 1911.

At both publications Millard worked closely with a journalist and writer Carl Crow, a fellow Missourian.

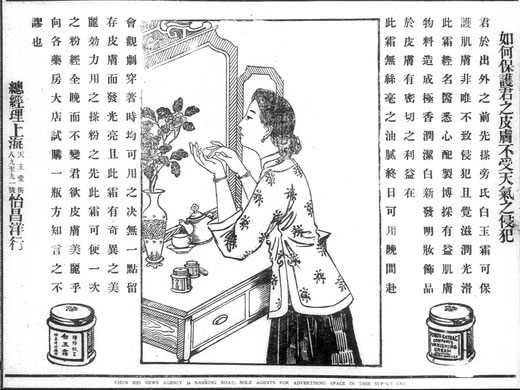

In the fall of 1918, the visionary Crow founded the Chun Mei News Agency, which was incubated in the premises of the Millard Publishing Company.

A closer look at some of Pond’s first Chinese advertisements reveal that they were in fact booked by Chun Mei.

After Crow had a fall-out with the other partners involved in Chun Mei, he took the advertisement accounts and went on to found his own ad agency, Carl Crow Inc, in 1920, with Pond’s most likely as its very first client. This partnership would soon become the most influential one in Chinese advertising and, some argue, of the early history of the country’s modern popular culture.

According to Paul French, who wrote the excellent biography of the legendary ad man, Crow was a master in self-promotion and claimed that with his early Pond’s campaigns he had personally revolutionized the female beauty market in China with his combination of sexy girl images and accompanying text. Historian Tani E. Barlow, goes as far as proposing that Crow’s early visuals for Pond’s heralded the entire modern girl image in Shanghai advertising, that was to become ubiquitous throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

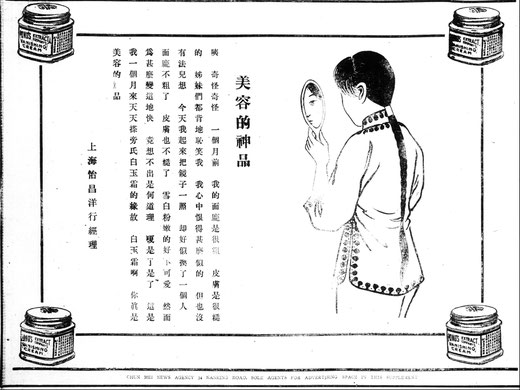

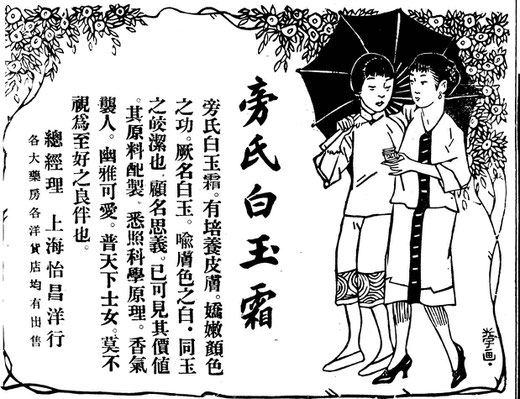

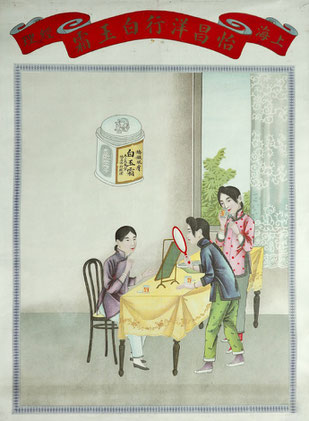

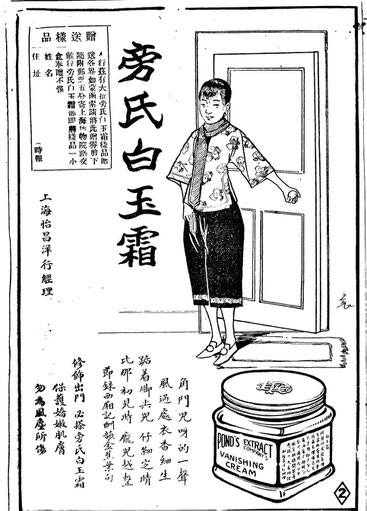

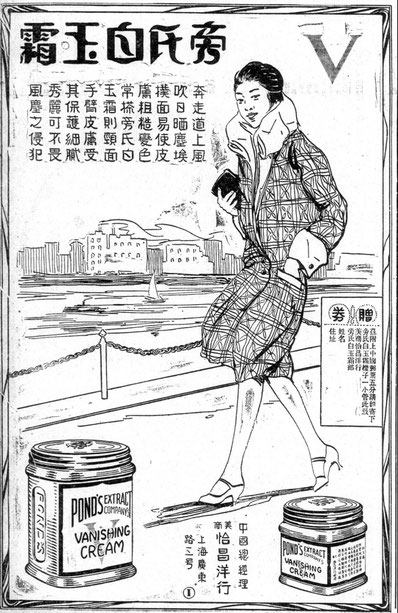

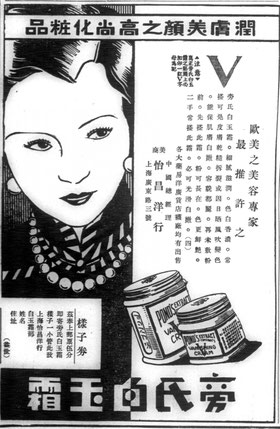

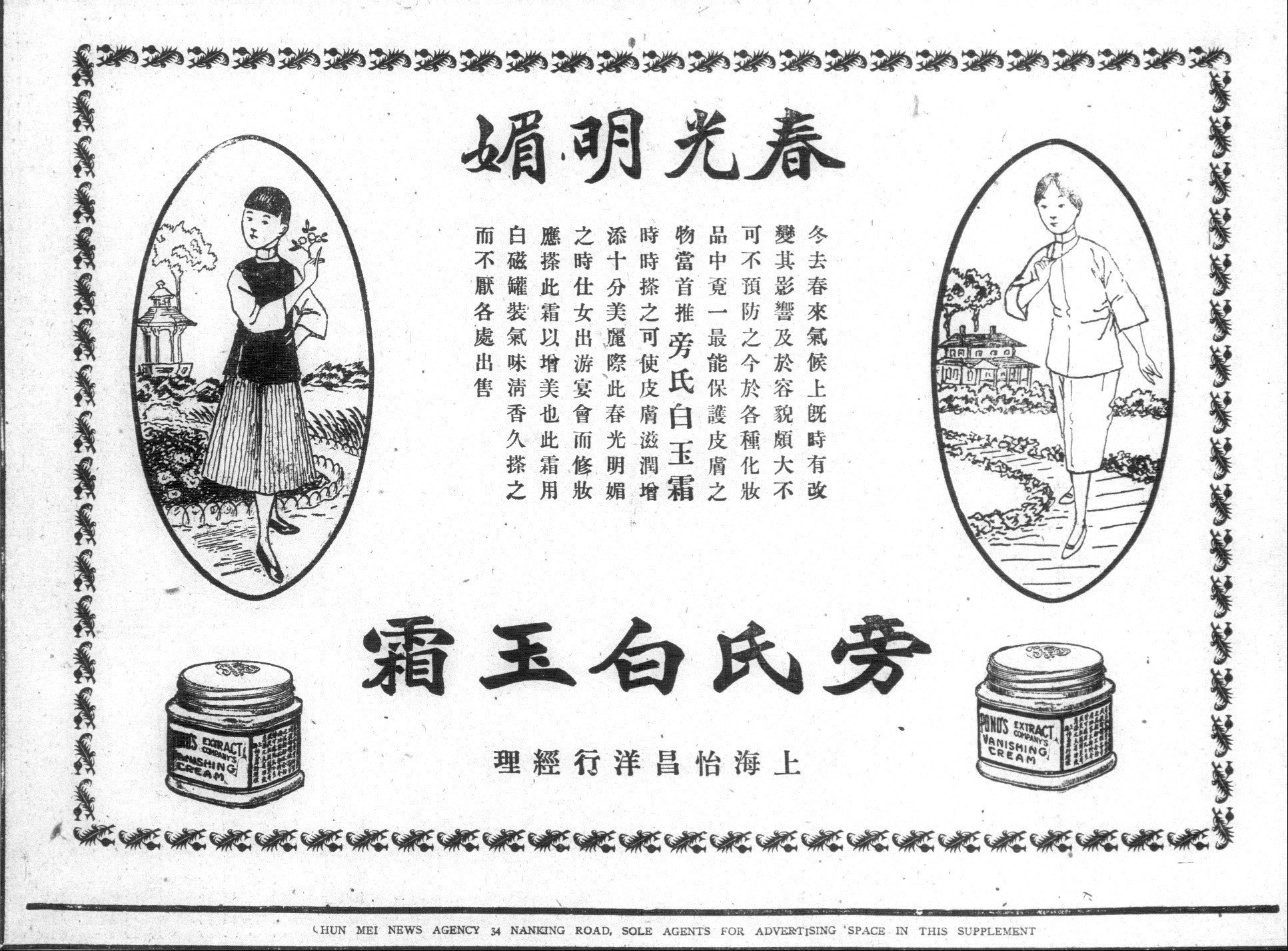

In 1919 and early 1920, Crow indeed took the iconography of Pond’s global lead agency, J. Walter Thompson, had the pictures redrawn to a more fitting Chinese style and experimented with various motifs such as a cosmopolitan modern girl, a traditional lady and a young mother who all unanimously favor Pond’s face cream out of their universal pursuit of perfect skin. The most successful ads, which were all published in China’s largest newspaper, the Shenbao, turned out to be the ones depicting the modern girl, staggeringly ahead of her time in her avant-garde dress, admiring her own reflection in the modernist dressing room mirror.

Another winning motif was the “curious girl”, dressed in traditional Chinese garb, who was introduced to Pond’s Vanishing Cream by a more sophisticated friend, whose modern orientation was indicated by her Western-type high heel shoes. The curios girl archetype was a progressive icon already familiar to Chinese women from illustrated story magazines, but according to Crow, he was not only the first to place vanishing cream advertising in Chinese papers, but also the first to combine the image with industrial commodities for the purpose of advertising.

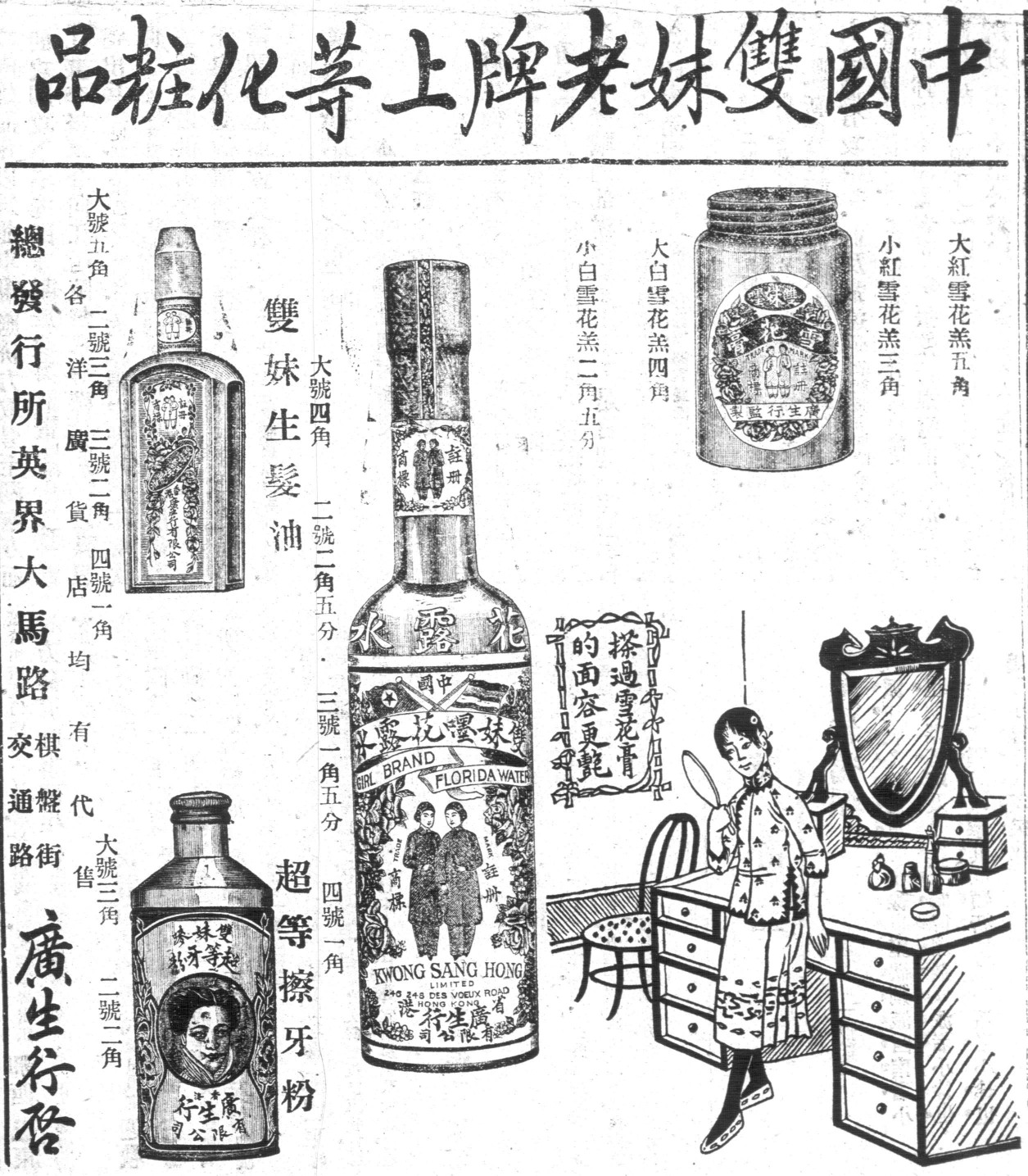

Our research shows that in reality, the pioneering cosmetics company Kwong Sang Hong from Hong Kong had already experimented with beautiful young girls depicted alongside their “Two Girls” vanishing cream (雪花膏) in ads since as early as 1916.

It was also them, who on December 31st 1917 published the first cosmetics advert with the curious girl motif, combining all the visual elements that Crow lifted for his Pond’s campaigns two years later.

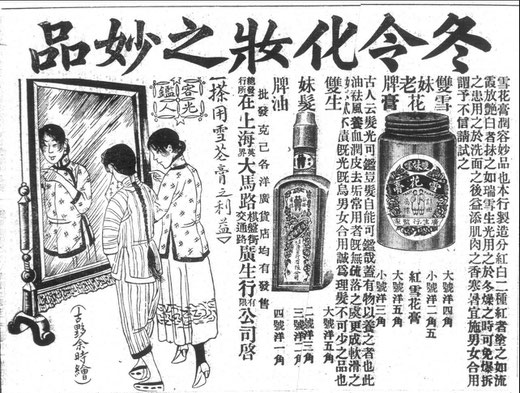

Encouraged by the positive response to his early 1919 ads, Crow continued to innovate and during the early 1920s developed major new iterations. Crow’s artists added narrative content, placing the girl in a modified bathroom, for instance, but without altering the key elements, the mirror or vanity mirror, the girl, and a commodity image. A crude advertisement poster from this early period proves that Crow also expanded into other mediums, bringing the scene from the newspapers to an even wider audience by having it plastered on walls across China.

To sell Pond’s, commodity adverts had to teach potential consumers the proper uses of the new cosmetic cream. Another winning tactic to achieve this, according to Tani Barlow, was that Crow decided to merge cosmetics with soap advertising and increased the number of soap ads in ‘‘all the leading newspapers and magazines’’ to create repetitive, instructional copy. It was Crow’s opinion that Chinese women of all but the poorest classes already used rouge and talcum powder, so his Pond’s cream copy chose to emphasize two modernist aspects of cosmetic use: hygienic preparation of the skin and social liberation.

In 1925 Crow dramatically increased the response to Pond’s marketing in China by including a call to action on the adverts: Chinese newspaper readers could send five to ten cents in stamps by mail, for which Crow then sent them samples of vanishing cream or cold cream. Each remittance of postage stamps had to be accompanied by a coupon clipped from the advertisement.

The combination of the modern girl image with modern advertising methods made Pond’s one of the most frequent advertisers in Chinese publications during the 1920s and soon dominated the market, leaving behind its competitors Kwong Sang Hong’s “Two Girls” vanishing cream, Burroughs & Wellcome’s Hazeline Snow cream, Chesebrough’s Vaseline or Allen & Hanbury’s Hazel Bloom Foam, all of which had entered the Chinese market several years prior to Pond’s.

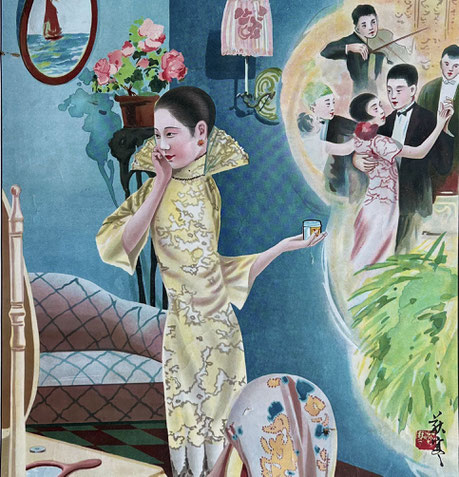

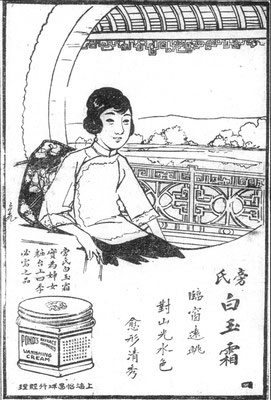

A final stroke of genius conceived by Carl Crow Inc., leads us to our 1929 advertising calendar poster, which represents the culmination of everything that made Pond’s so dominant during Republican China.

For quite some time Crow had been planning to issue a style book for Chinese women. The idea came to him from the fact that some of the small rural newspapers sometimes borrowed the printing blocks and published Crow’s Pond’s Vanishing Cream posters and newspaper adverts for free, because his artists always drew the girls wearing the latest Shanghai styles, and smart-up country ladies gave these pictures to their tailors to copy.

In his 1937 book “400 Million Customers” Crow recalls how, “…we sometimes introduced, on our own initiative, some novelty to the skirts and it was always great fun to check up and see how far our ideas were carried out.”.

The distinctive stand-up neck collar featured in our advertising poster could clearly have been one of such creative innuendos. For later iterations of the motif, he boasts how, “we always featured the slit skirt, sometimes introducing, on our own initiative, some novelty such as having the slit on one side a little higher than on the other”, and continues to write, “I am rather proud of the fact that we played our small part in revealing the most beautiful leg the world has ever seen.”, alluding to the iconic, tight-fitted and shorter Shanghai-style Qipao, or Cheongsam as it is also known, emerging in the 1930s.

Although our 1920s poster does not reveal the legs of the Modern Girl yet, it is revolutionary in another sense. The illustrations mise-en-scene is meticulously laid out, with the established elements of the sexy icon in her European-style bedroom, applying Pond’s cream, while gazing into the mirror of her dressing table. But unlike any other previous calendar advertisement, it not only depicts the usage of the cream, but builds on the aspirational character of the product, flaunting its ultimate benefit. In a dream bubble, the Modern Girl envisions herself in a gorgeous night dress, with in vogue bobbed hair, dancing in a colonial ballroom with her dapper admirer, dressed in a Western suit and his hair stylishly slicked back.

The artist responsible for this clever juxtaposition is revealed by his signature as Zhāng Díhán (张荻寒). Zang studied in the training school of the Commercial Press and worked as a freelancer for among others the Huacheng Tobacco Company and Carl Crow Inc.

The earliest known calendar poster advertisement for Pond’s is from 1925, but it only depicts the curious girl character in a classic dressing room scene. Another surviving example from 1927, which is also part of our collection, shows a young woman in an outdoor setting with a more traditional loose-fitted dress with silk capelet, though her short hair, the ostrich feather boa and the Western style kitten-heels do give a hint of the impeding social revolution which Pond’s and literally all other brand advertisers were soon about to set loose.

It is our 1929 edition however, which marks the turning point of the “Modern Girl” in her ethereal transcendence from the dressing room into the vibrant social life of late 1920s Shanghai. In Carl Crow’s own words, “The Chinese woman has broken out of the inner courtyards of the Chinese home and nothing will ever put her back again”.

As the country entered the 1930s, the Modern Girl in Pond’s advertising became more sexy, progressive and emancipated. Her skirts got shorter, her eyebrows thinner and she was now even depicted driving her own automobile.

Since the start of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the Western-controlled parts of Shanghai represented a last idealized bastion of cosmopolitan life, but when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and invaded the International Settlement it put a harsh end to the epitome of modern Chinese consumer culture. Pond’s activities in China came to a standstill, which even after the war, the brand would not recover from and it abandoned the country for over 40 years.

It was only after the market reforms of the late 1970s, that the Chinese “Modern Girl” was awakened from her beauty sleep and her strive for Western products reinvigorated. Unilever was among the first multinationals to enter the Chinese market after the opening up in the 1980s. In 1987, the company acquired Pond’s as part of its brand portfolio, uniting it under one roof with its old competitors Hazeline Snow and Chesebrough’s Vaseline.

Once again, the brand is sold in China, but today it is no longer confined to only modern girls. Even China’s most famous online influencer and “Lipstick King”, Austin Li has discovered Pond’s, expanding its messaging to an entirely new persona – that of the metrosexual “Modern Boy”. Carl Crow would have approved.

Write a comment