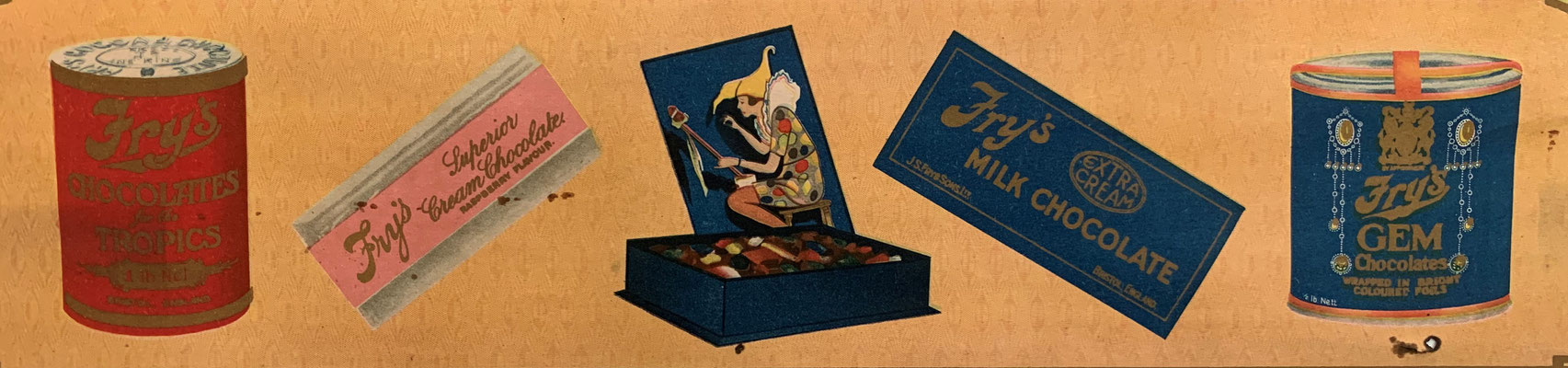

A sophisticated Old Shanghai lady relaxing with a bite of Fry’s chocolate at her country home. Her bamboo flute (or is it maybe an opium pipe?) close beside her. What in 1927 may have sounded like an intriguing value proposition for J.S. Fry & Son’s in the Middle Kingdom, turned out to be nothing but a pipe dream….

Joseph Fry from Bristol, England started making chocolate around 1759. After several changes of name and ownership, the business became J. S. Fry & Sons in 1822. In 1847, Fry's produced the world’s first solid chocolate bar and also created the first filled chocolate sweet in 1853. In 1919 it merged with Cadbury's chocolate and the joint company was named "British Cocoa and Chocolate Company".

Cadbury's had been trying with little success to sell chocolate and cocoa to Chinese consumers since the end of the 20th century. In 1919 British trading firm George McBain inherited the account from Walter Nutter & Co. aka “Kung-Fah” and in 1924 another attempt was taken to popularize the sweet delights among the Chinese: Shanghai adman Carl Crow was hired who conceived a new strategy for the business: Fry’s (translated as 富来氏父子有限公司) range of hard chocolates was to be positioned as a luxury treat for the upper classes, while the Cadbury brand was to be abandoned altogether and instead its Bournville cocoa brand marketed to the masses. For the latter Crow’s approach was to emphasize its health appeal, specifically for curing insomnia and constipation. And so large-scale and expensive marketing campaigns were rolled out during 1924 and 1925 incl. baking contests, educational brochures, print adverts, outdoor billboards and calendar poster advertisements.

Unfortunately, after one year of an intense advertisement push still barely any Chinese were buying Bournville cocoa, let alone Fry’s chocolates. The British Cocoa and Chocolate Company back in England was furious. Not only didn’t the promised sales materialize, but the firm also strongly disagreed with Crow’s strategy to position their products as tinctures for chronic indigestion or insomnia. Even the typically boastful Carl Crow admitted his failure, retelling the episode in his book “400 Million Customers”:

"We were rather proud of ourselves when we wrote to the British manufacturer telling him what we had done. Unfortunately for us, the manufacturer did not share our enthusiasm. He did not approve of anything we had done. Though he wrote to us with some Quakerish restraint, his words were biting enough as they were, and much could be read between the lines. The reputation of his old and respectable firm had been dragged in the mire by our blatant and unethical advertising. He took no more chances with us but turned the advertising over to another agency who could be trusted to maintain the respectability of the firm no matter how much that high estate might cost in the loss of sales opportunities."

Even with the new agency Bournville continued to struggle throughout the 30s & 40s and the Fry’s brand was discontinued altogether already in the late 1920s: unsurprisingly, shipping British-made chocolates all the way to China from England and then distributing them in the Chinese summer heat turned out not to be feasible business. After the Communist Revolution Cadbury’s abandoned the Chinese market and did not return until in the 1980s. Fry’s however to this day has not been re-introduced, making our calendar poster the very last artefact of the brands aspirations in China.

Write a comment