A kerosene lamp branded by Lockwood Bros, Pampa, Sheffield and Shanghai Rex & Co (公发英行 - "Kung-Fah" ). From the MOFBA collection.

A beaten-up old kerosene lamp – like most exhibits in our collection, it is of little material value. But the history it encapsulates in its rusty innards only becomes more valuable as the years pass. It feels as if, on our countless expeditions through the historic buildings, flea markets, and antique shops of China, it is not us who discover these artefacts but rather them that find us, whispering their plea and begging for someone to retrieve them and release the genie of their former masters' stories. Cautionary old Chinese business tales of fortunes won and lost, greed, betrayal, and early death in a faraway land. This is one of them. This is the story of Kung-Fah.

The details as in the coroner's inquest were not in dispute. It was around two o’clock in the morning when A-Mow, the houseboy, was awoken by the scream of the laodah: “Man overboard!”. The engineer heard a splash, as if a man had fallen into the water and immediately stopped the engines of the steam launch. When he jumped out of the engine room, he saw a mass of white clothes on the left side of the boat in the water and immediately alerted the laodah, the skipper of the boat. By now, the entire Chinese crew was on deck and looked at each other in bewilderment; none of them was missing.

A-Mow rushed to the cabin at the bow of the boat, where his master and mistress slept. He found their door wide open, as it was a warm night. But the mistress was alone in her bed, still sound asleep. “Master have got?” he shouted, waking the missus. Torn from sleep and still dazed, she in turn yelled at A-Mow, "Where's my husband? How is he not here!", and it was only at this point that the poor boy realized what had happened.

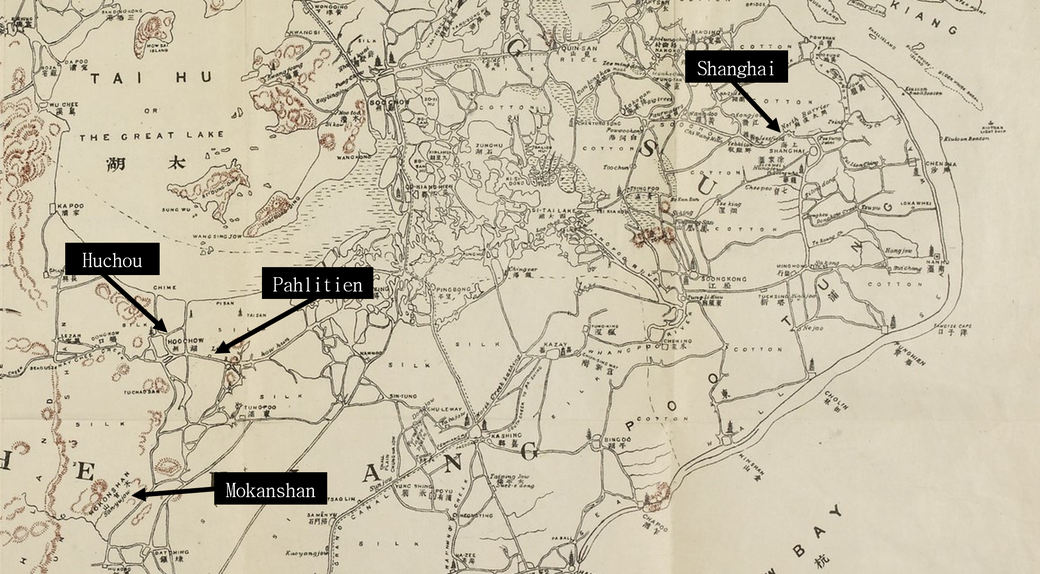

Even though the engines were stopped, the launch still went on through a bridge some 60 or 70 feet. They turned the boat around, lighted the oil lamps, and used bamboo poles to search the water, calling and shouting till daylight. When they could not find a trace, they went on to Huchou, where the mistress knew a missionary, Mr Hearn.

They returned to the bridge at the village of Pahlitien mid-morning, together with two missionaries and six Mandarin boats with fishing nets. The men asked for 14 dollars to retrieve the corpse, and after it was granted, the body was brought up and drawn to the shores in less than one minute. The frantic wife and the missionary Dr. Eubank made attempts to resuscitate the man, but to no avail: the body had been in the water for over seven hours at this point, and Mr. Alfred Beilby Rex was declared dead at 10 a.m. It was Wednesday, the 31st of May, 1905 and Alfred was only 51 years old.

Alfred and Mary Jane Rex had only left Shanghai the previous day at eight o’clock in the river launch borrowed from Alfred’s friend Archibald J. Little to go up to Mokanshan. The day after the tragic death, an inquest was launched when Mrs. Rex, Minister Alexander Hearn, Ng A-Mow, the houseboy, and Zi Ah-Si, the fireman on duty in the engine room, gave their accounts of the dreadful night. The splash was heard between the laodah’s room, which was in the middle of the boat, and the engine room, which was at the back . The cabin was located at the bow, and there was a walk past the engines to get to the stern. “Anyone passing along this would be behind the man at the wheel and would have had to sneak very quietly not to get noticed,” Zi Ah-si explained. Mrs Rex recalled that her husband always maintained he could swim, although he was not an expert swimmer. She was sure it must have been an accident and knew of absolutely no reason her husband would take his own life. “No one had a keener hold on life,” she sobbed.

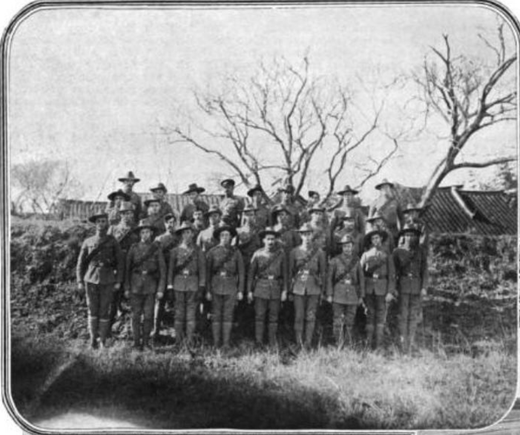

At the conclusion of the inquest, the verdict returned, stating it was a death by accidental drowning. Oddly, not a single obituary was published in the local newspapers, even though Alfred had been an esteemed taipan of the Shanghai business community for close to 30 years, captain of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, president of the Shooting Committee, treasurer of the Temperance Union, and president of the Mokanshan Summer Resort Association.

Was the innocent Victorian-age Mrs. Rex not fully aware of her husband’s business dealings in the colonial outports of Cathay? And might there have been more to his sudden passing? Let’s explore commercial history and shed more light on the circumstances of Alfred’s business undertakings in early 20th-century China …

Alfred B. Rex was born in 1854 to a Baptist pastor in the suburbs of Wimbledon, London. He landed in Shanghai from Marseilles via a steamer sometime in 1877, where he secured work with the British merchant firm Iveson & Co. Shortly after his arrival, he joined the Shanghai Volunteer Corps in the rank of corporal to offer his skills as a part-time military man. He would soon win the acclaimed Municipal Challenge Cup in 1879. The up-and-coming business executive Alfred married Mary Jane Namways in Shanghai in 1885 and fathered four children, only two of whom survived their early years – Alfred Maurice and Phyllis Marjorie.

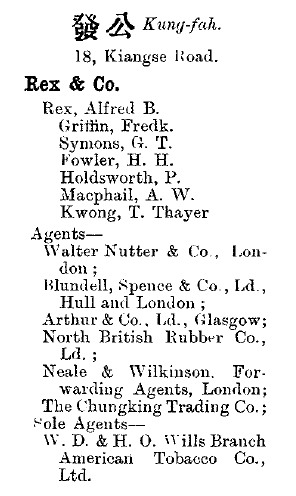

After close to ten years of supporting British brands in the recently opened Chinese market with Iveson, and encouraged by the boom of the post Arrow War and Taiping Rebellion Imperial China, he finally decided to launch his own Shanghai trading firm, Rex & Co., in 1888. As his Chinese “Hong” name, he chose Kung-Fah (公发英行) – whose English equivalent would be the “Common Prosperity British Trading Firm” – reflecting his approach to business rested in his Baptist ideals in the colonies.

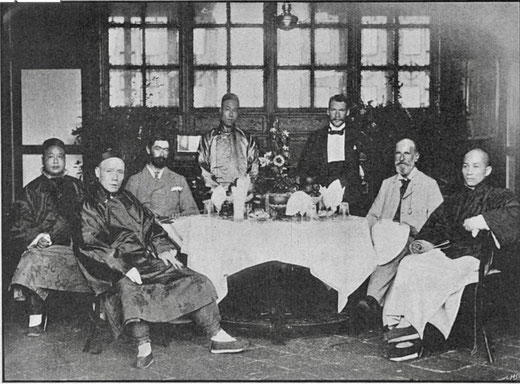

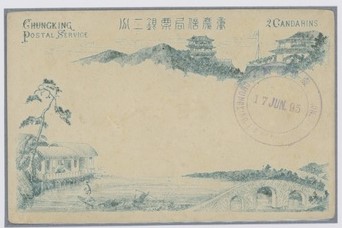

His newly incorporated firm’s main collaborator in China was fellow Brit, Archibald J. Little, the founder of the renowned Chungking Local Post and subsequent Chungking Transport Co. The two hands met and bonded in the Corps. After Archibald served on the Shanghai Municipal Council in 1880, he founded his shipping enterprise in 1882, opening up Western China to foreign commerce when he first ascended the Yang-Tse rapids in a small steamer to Szechuan. While Archibald had a “facile pen and a robust constitution”, he generally encompassed all the “requisites of a traveller and pioneer rather than those of a merchant.” On the other hand, Alfred complemented the Kung-Fah endeavour with his day-to-day trading experience and stable “Christian character that made him a favourite with the missionaries,” as stated in the commemoration by the Mokanshan Summer Resort Association honouring the late Mr Rex.

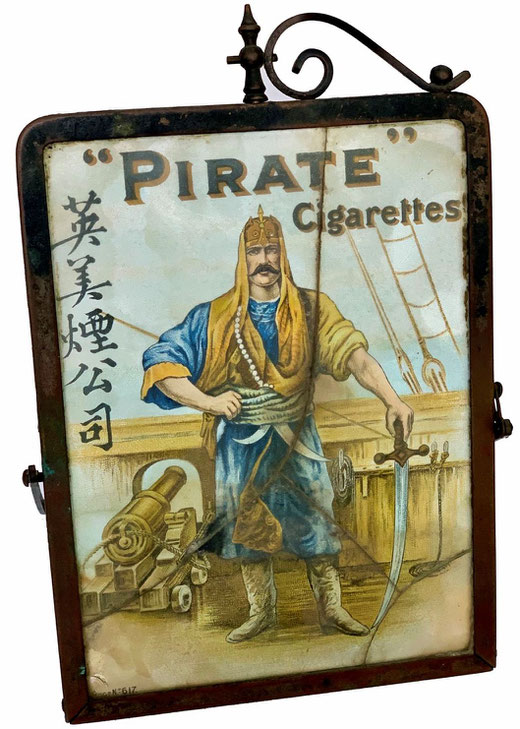

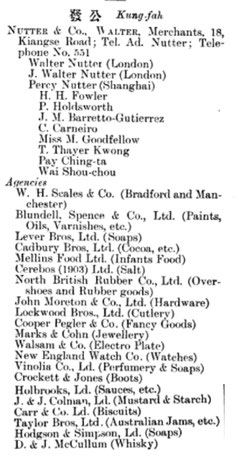

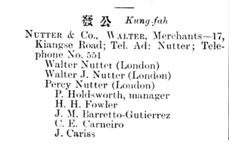

The first and most valued partner that Rex & Co. associated themselves with in the Empire’s homeland was Walter Nutter & Co., who offered representations for renowned British firms such as Blundell, Spence, Arthur & Co., North British Rubber, Neale & Wilkinson, and Cadbury Bros. The biggest account of them, though, was the tobacco brand W.D. & H.O. Wills – early mass producers of machine-made cigarettes and owner of Pirate and Ruby Queen cigarettes – two of the most famous foreign cigarette brands in China up to the 1990s! Rex & Co had won the exclusive distribution rights in 1891.

Lockwood Brothers from Sheffield, manufacturers of cutlery, knives, files, and other tools, was another early brand account represented by Rex & Co. via Walter Nutter. They were, in fact, the advertiser of our branded kerosene lamp promotional merchandise, which bears both their name in English as well as Rex & Co's Chinese name “Kung-Fah” on the inside. Was this artefact one of the kerosene lamps Alfred had brought on board, for what would be his final journey? And did it and its companions fail to illuminate the river bright enough to rescue their master from drowning? After all our lamp found us at an old Chinese antiques dealer in Chungking – Archibald Little's home base of many years and to where he might have taken his river launch again after the terrible accident in Chêkiang. Then again, Archibald returned to England in 1907, where he died one year later in 1908, and the lamp might have stayed with Rex & Co in Shanghai. Let’s dive back to Kung-Fah’s development in the early years of the new century and investigate further.

While Alfred Rex moved up to the ranks of captain at the Corps and his China import business was flourishing, the tides turned for corporate interests in the 400-million Chinese consumer market for cigarettes.

In 1902, British American Tobacco (BAT) Ltd. was formed when Britain’s Imperial Tobacco Company and the United States’ American Tobacco Company (ATC) agreed to form a joint venture. Rex & Co. had distributed Wills' high-class products directly to retailers in Shanghai but had also successfully utilized a group of Cantonese tobacco merchants named Wing Tai Vo to distribute the company’s cheaper brands, much to the Bristol firm’s satisfaction.

In terms of distribution arrangements though, not only Rex & Co. but also American Mustard & Co. initially acted as sales agents, with both maintaining their existing responsibilities for American and British cigarette imports, respectively. This dual arrangement was clearly considered unnecessary in the longer term; however, it was quickly revised in favour of the ATC’s former agency.

In 1903, BAT Ltd. bought the controlling interest in Mustard & Co. Soon after, it was decided to completely dispense with the services of Rex & Co. Significantly, Alfred was required by the agreement to terminate his use of influence with the Wing Tai Vo Company, inducing them to obtain their tobacco products from Mustard & Co. Following Rex’s withdrawal, the agency for the British brands was turned over to Mustard & Co., who thus became BAT Ltd.'s sole distributors within Shanghai and for a distance of 100 miles around the city. Alfred agreed to comply with BAT’s wish to discontinue his firm’s agency, in return for an immediate payment of £750, followed by further annual remittances of £500 over a five-year period. For its part, Rex & Co. covenanted not to undertake operations in the tobacco business in China for a period of fifteen years and bitterly agreed to the concession , which was barely worth the initial compensation and five-year earn-out plan, considering the long-term opportunity costs in the Chinese market for Alfred.

Although he had not directly experienced the impact of the Taiping Revolution between 1850 and 1864 on foreign trade, he heard enough from his friends adventure tales: Archibald barely escaped with his life multiple times during these tumultuous times. Alfred himself though did still live through the years of the Boxer Rebellion – an uprising against foreigners that occurred in China from 1899, which was begun by peasants but eventually supported by the government and ended in 1901 – and how it had influenced Chinese consumers’ appetite for foreign products down to straight boycotts.

In fact, on 5th September 1900, Alfred had written an agitated letter to the editors of the North China Daily News to raise awareness and calling for more British government support in the waging battle across China to suppress anti-Western rebels. “You think that these beastly cruelties practiced by the Chinese savages ought to be published. Why is it that no account has been written about the murder of 14 British in Chüchou, Chêkiang Province?” he asked in it. Even Baptist ideals had their limits it showed...

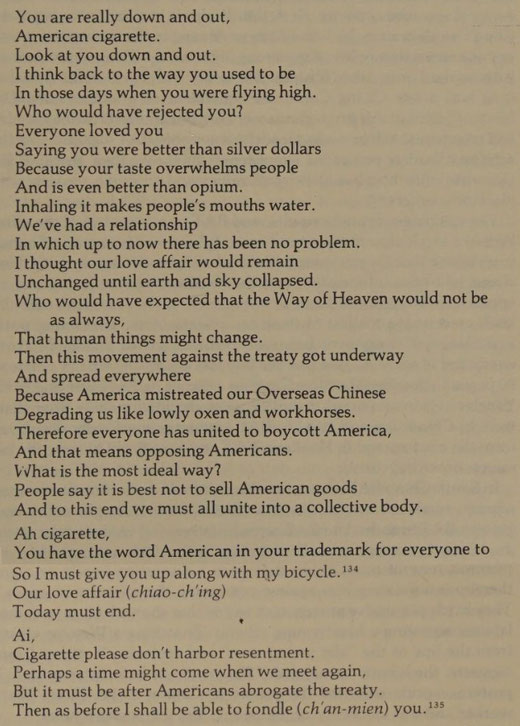

Then, just two weeks before Alfred’s untimely death on May 10th 1905, the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce had published a proclamation of a boycott on American goods, triggered by the Chinese overseas in the United States protesting against anti-Chinese violence there. The conditions were not met, and that spring, a boycott spread to ports up and down the Chinese coast. For months, Chinese consumers refused to buy, merchants refused to sell, and dockworkers refused to handle exports from the United States. An immediate impact felt on Alfred’s earn-out, now dependent on BAT’s success: within a week after the boycott began, BAT’s management in Shanghai complained that the company’s posters had been damaged, that Chinese clients had been intimidated, and that business was suffering. There was also a viable threat of spill over effects on other Anglo-Saxon enterprises, including Rex & Co's other British brand representations.

Ironically or circumstantially, Alfred was no stranger to drowning accidents in this lifetime. He had been called for jury duty twice during his stay in Shanghai. The first time was in July 1880, when an inquest was launched on the circumstances surrounding the death of Heinrich Stander, a seaman belonging to the British barque Highmoor, whose body was found in the Whangpoo river. Then again, in November 1902, Alfred was listed as a juror in the inquest regarding the death of James Jones, the stoker of H.M.S. Alacrity, who had fallen overboard and drowned. “The deceased must have sunk almost at once and not risen again, even though he was able to swim,” reported the North China Herald and Supreme Court & Consular Gazette.

Knowing all of this, did Alfred really accidentally fall over board that night? Or were the loss of the W.D. & H.O. Wills account, taken by the Americans and the recent threat of new anti-Western boycotts too much for him to bear? Was there maybe even a Chinese curse laid upon the name of Kung-Fah after Alfred's hateful diatribe against the Chinese in the North-China Daily News?

After the death of Alfred, his widow Mary Jane sold Rex & Co. to its former British partner, the export firm Walter Nutter & Co. Devastated and disillusioned, she left Shanghai with her two children in 1907 and passed away in Highgate Middlesex in 1927.

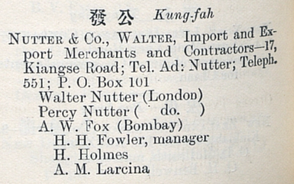

Nutter & Co. was founded in 1881 by Mr Walter Nutter, Sen., and listed among others were Lever Bros. Ltd., Cadbury Bros., Spence & Co. Ltd., and J. McCallum (distillers of “Perfection Whiskey") as its clients. While the eldest son Walter Nutter Jr. managed the business with his father back in England, the younger son Percy John Nutter was sent to Shanghai to take over and integrate the remains of Rex & Co in 1906. The Shanghai firm’s English title was renamed to Nutter & Co., but it’s fateful Chinese trade name “Kung-Fah” was retained, building on its well-established reputation among Chinese merchants and trade partners.

Most of Rex & Co's former employees left the firm after the take-over, but two men decided to stay on board with the new owners: Percy Holdsworth and Herbert Henry (H.H.) Fowler. Both were Shanghailanders, born & raised in the city, and saw their chance to eventually advance to head of Nutter & Co's Shanghai branch once Percy Nutter moved back to London again.

But not only did Percy Holdsworth share the same first name with the young Nutter, he was also 10 years H.H.'s senior. And so, as to be expected, in 1909 Holdsworth was promoted to manager of Kung-Fah Shanghai while Percy Nutter returned to Britain.

The decision did not sit well with H.H. Fowler, an ambitious and athletic young man of only 26 years. He looked down on Percy Holdsworth, who he considered a weakling and a boozer who "just got lucky". His drinking had in fact gotten even worse since his mother died on Christmas Day from heart trouble.

While H.H. recently had gotten married, Holdsworth still lived in the bachelor apartments of the Kalee Hotel, conveniently located on "The Line" of Kiangse Road where both the Kung-Fah office and Gracie Gales infamous bordello were located a few foot steps apart. Once Percy Nutter left China, rumour had it, Holdsworth spent more time in the latter establishment than in the office during the early summer of 1910.

On July 29th, just like every day at 7 a.m., the room-boy of the Kalee went to room No. 112 to wake master Holdsworth, but to his horror found him lying dead in his bed. A post mortem examination of the body showed no signs of violence and the coroners inquest concluded that death had occurred due to "the diseased condition of the heart". The North-China Herald issued the notice of Percy Holdsworth death at age 36 on August 5th 1910.

Two of the Shanghai evening newspapers though reported a different story. One of them speculated that the deceased had committed suicide by taking poison and the second one alleged that Holdsworth had "threatened to jump into the river at Woosung some days ago". Another tragic coincidence, another lost soul taking his own life or the curse of Kung-Fah striking once more? What would happen with the Shanghai firm now that a second of its managers passed so unexpectedly and who would dare to take over the leadership from here?

H.H. Fowler could not have cared less about purported Chinese curses nor the death of his rival Holdsworth: as the second-in-line, his time had come to be promoted to manager of Kung-Fah and lead all of Nutter & Co's China import business. Unheard of, even among the "Shanghai 400" foreign elites, for a man only in his mid-twenties to achieve such a position.

One year later the Xinhai Revolution toppled the hated Manchu-led Qing Dynasty and with that collapsed the thousands year old Chinese monarchy. Both H.H. and his company Kung-fah survived the turbulences unscathed and a bright future lay ahead in the new Republic of China established on January 1st 1912. Had luck finally turned for Kung-Fah and its leaders?

You might not believe us, when we report on what happened next. But rest assured, that not a word of this story has been fictionalized - all sources are available in public records and news archives.

Just a few days after the Republic had been proclaimed in China, young Walter Nutter Jr., who had by now taken over his family business, died in London at the mere age of 38.

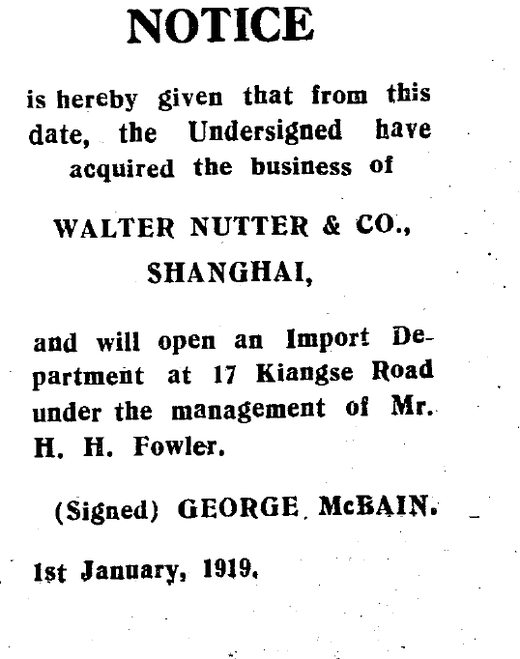

Eight years later in 1920, Walter Nutter Sr. passed away in Essex. With the Great War’s end, his brothers’ premature death, and the father’s failing health, the only remaining son, Percy, already felt he had no choice but to sell the Chinese operations of Nutter & Co in 1918. And so, it was announced on 1st January 1919 in the North China Daily Herald that the famous British conglomerate in China, George McBain, (麥邊洋行) had acquired Walter Nutter & Co., and with that formed its own import department under the management of Mr. H.H. Fowler, former Rex & Co's only remaining employee. The old trade name "Kung-Fah" was irrevocably discarded as the operations were absorbed into McBain ("Mai-bien" in Chinese), marking the end of its 30 years long existence in the Middle Kingdom.

With the discontinuation of "Kung-Fah", also its dreaded curse seemed to have finally been lifted: Herbert Henry Fowler successfully continued his career at George McBain, before he joined Brunner, Mond & Co China in 1926 as sales manager and ultimately even became one of its Managing Directors in 1929. He died in 1968, in the town of Battle, Sussex, England, at the age of 84.

Sadly (or fortunately?), little remains of Alfred B. Rex’s and Kung-Fah's legacy in China apart from the one rusty kerosene lamp in our collection - the genie and its curse locked safe inside.

Write a comment