This German-language advertisement booklet from our collection is by itself a bit of a conundrum, but also reminds us of a puzzling episode that happened at the hotel during the Battle of Shanghai in 1937.

We have previously written about the marvelous Joint Savings Society building, designed by famous Shanghai architect László Hudec and housing the Park Hotel here.

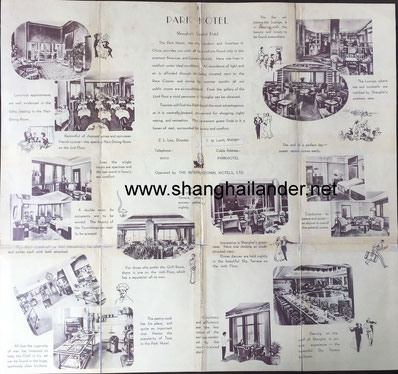

Today’s featured artifact however tells us more about the actual amenities of the hotel, albeit in rather poorly written German which was quite obviously translated from an English original text. Nonetheless, here are some of the key take-aways before we delve into the more intriguing part of the story: The Park Hotel was opened in 1934 on the intersection of Bubbling Well Rd. (now Nanjing West Rd.) and Park Rd. (Huanghe Rd.), and belonged to the International Hotel Ltd. – a purely Chinese owned consortium.

Conveniently located in the heart of Shanghai, just opposite the racecourse, the Park Hotel was the tallest building at 22-stories not only in Shanghai, but in all of East Asia. Our brochure highlights how this allowed a panoramic view over the entirety of Shanghai and how even the mountains of “Quinsan” (presumably Kunshan) and “Chasan” (Sheshan?) could be seen from the top.

The booklet furthermore reveals that an artesian well, located 700 feet below the hotel, provided water for the entire building. In terms of facilities, the hotel boasted a spacious dining room, the “Grill room”, a roof terrace, a lounge, the “American Bar” and over 200 rooms including single rooms, “Duppel Zimmer” (a spelling mistake for double rooms), lavish apartments and private salons. The discerning clientele could additionally avail themselves of two separate hair salons, tailored exclusively for ladies and gentlemen. The building featured three state-of-the-art automatic Otis elevators, whisking guests upwards at a remarkable speed of “600 feet per minute”, in addition to three additional freight elevators.

The interior design of the hotel was meticulously curated, with contributions from Arts & Crafts, Tai Chong, and the renowned Sincere Co. department store. The German brochure proudly highlights the use of exquisite “Austrian nutwood” in the enchanting Grill room, while the restaurant boasted a “complete set of Berndorf silver cutlery”, specially imported from Austria.

The restaurant operation alone employed a remarkable 180 waiters and from press reports of the hotel’s grand opening we know that in total it retained over 300 employees.

Our brochure also lists a floor plan and reveals that the 21st floor featured a viewing gallery while the 22nd floor was the observation deck of the Municipal Fire Brigade.

An interesting claim additionally made in the booklet was that, “although the Park Hotel is the poshest hotel of Shanghai, prices are – in relation to the luxury and comfort – very low.” Conveniently, our booklet also contains an inserted price list, allowing us to cross-reference and compare the actual costs with today's standards.

Although the brochure and price list do not explicitly mention the year of their creation, we can reasonably infer that it is most likely from 1935 based on the listed Chinese members of the board of directors and their respective titles. For instance, W.W. Yen (颜惠庆) was Ambassador to the U.S.S.R. from January 1933 to August 1936 and Z.L. Loo (卢寿联) only joined Reliance Motors in January 1935.

The prices listed are in Chinese Dollars, with one Chinese Dollar in 1935 being equivalent to 36 USD cents. A high-end double room, excluding breakfast, would have set you back for 22 CN$, which converted to USD and adjusted for inflation would be equivalent to 177 USD in today’s purchasing power. A dinner priced at 4 CN$ per person in 1935, today would be the equivalent of around 32 USD. Considering that the Park Hotel was the most prestigious and contemporary hotel of its time, these prices indeed appear quite reasonable, wouldn't you agree? That is of course only for the local Chinese and foreign elites as well as wealthy foreign tourists and business travelers.

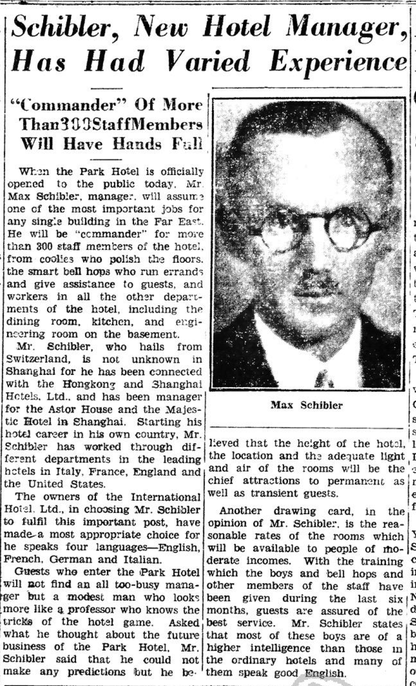

Lastly, the booklet introduces the hotels manager, Director Max Schibler, who would play a pivotal role in the enigmatic events that unfolded at the hotel two years later. Schibler, born in Walterswil, Canton of Solothurn, Switzerland, in 1899, received comprehensive training in hotel management at the esteemed Swiss Hotel Men's Association School in Lausanne, graduating with high honors. He amassed a wealth of experience working in prominent hotels across Italy, France, England, and even the illustrious Blackstone Hotel in Chicago.

In 1928, the Hongkong & Shanghai Hotels Ltd. brought him to the Orient as the assistant manager of the Hongkong Hotel. After a year, he was entrusted with the more significant role of assistant manager at the renowned Astor House in Shanghai. Schibler also held positions at the Majestic Hotel, eventually assuming the role of manager at the Astor House Hotel in 1930 before joining the Park Hotel in 1934. The press also lauded him as “a linguist, speaking English, German, French and Italian fluently”.

Herein lies the conundrum of our brochure: it was translated from English to rather sloppy German, with several grammar and spelling mistakes.

It is unclear whether "Professor" Schibler was involved in its creation and approval, or perhaps he became significantly preoccupied, contrary to what "The China Press" had portrayed during the hotel's opening. The newspaper had described how “guests who enter the Park Hotel will not find an all-too busy manager but a modest man who looks more like a professor who knows the tricks of the hotel game.” When asked about the future success of the new hotel, Schiblers prediction was that “the height of the hotel will be one of the chief attractions”.

This statement, though obvious, turned out to be an intriguing prophecy that would indeed be fulfilled, albeit in a manner far different from what the unfortunate Mr. Schibler had envisioned.

Soon after the commencement of the Battle of Shanghai on 13 August 1937, Schibler found himself not only amidst a war but also at the center of a diplomatic scandal and subject to a police investigation. Here is what happened.

By the mid-1930s the Shanghai International Settlement was governed by the Municipal Council in which the British and the Chinese each had five member seats, the Japanese two and the Americans and others two.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War erupted, Japanese troops only attacked the Chinese parts of Shanghai, which lay beyond the borders of the insulated International Settlement and the French Concession. Since Imperial Japan was not at war with the countries that administered these semi-colonial areas of the city, the foreign settlements maintained a stance of neutrality throughout the conflict.

In theory, the foreign concessions maintained their neutral status, only offering vital refuge for civilians seeking to escape the horrors of war. However, in practice, they inadvertently provided support to Chinese military intelligence, making the Park Hotel, as the tallest building in the city, an object of great interest.

Indeed, on the night of 24 August 1937 suspicious signaling lights were observed, emanating from what was believed to be the 15th floor of the famous edifice. The Shanghai Municipal Police conducted an investigation, and their Special Branch was dispatched to interrogate the hotel's manager, Max Schibler. He confirmed that the 15th floor had previously been occupied by Z.L. Loo, a director of the hotel, but since the outbreak of the war, it had remained unused.

In early October, additional questionable activities took place at the hotel, and on October 16th, the Japanese naval spokesman claimed to have definitive proof that Chinese officers were using the roof of the Park Hotel as observation posts. Once again, Schibler was compelled to issue a statement, vehemently denying these allegations. Instead, he specified that "the top of our building is occupied by the US Marine Corps as an observation post". Whether this statement reflected the truth or if the Swiss national Schibler had in fact stretched his neutrality by allowing Chinese military to utilize the vantage point, remains unknown.

What we do know is that Schibler now had the Japanese on his back, which was not something the feeble man could endure for too long before he cracked. In February 1938, he departed Shanghai with his wife Vellia, embarking on an “extended holiday to his home country”. They travelled via steamer, first to Japan, then Canada and the US before presumably reaching Europe. A journey he would never return from and in fact no trace of him was ever seen or heard again.

Although some newspaper advertisements still listed him as the manager as late as January 1939, he was eventually replaced by a new manager named T.M. Lamb, as seen in a later-modified brochure from the collection of our friend at Shanghailander. In retrospect, Schibler's decision to leave Shanghai was undoubtedly a wise one. In December 1941 Japanese troops stormed the International Settlement, soon interned residents of the Allied powers in camps, and ruthlessly pursued anyone who had collaborated with the Chinese nationalist government, regardless of their nationality or neutrality.

P.S. According to the autobiography of Lin Mianzhi (1907-1998) there were the following foreign managers of the Park Hotel after Schibel: Hertzel, Lamb and Vogel, none of whom stayed for a longer period of time. In June 1943 the long-time employee Lin Mianzhi himself took over the office and managed the hotel throughout the war years.

Thank you to Katya Knyazeva at https://avezink.livejournal.com/, who contributed to this article!

Write a comment