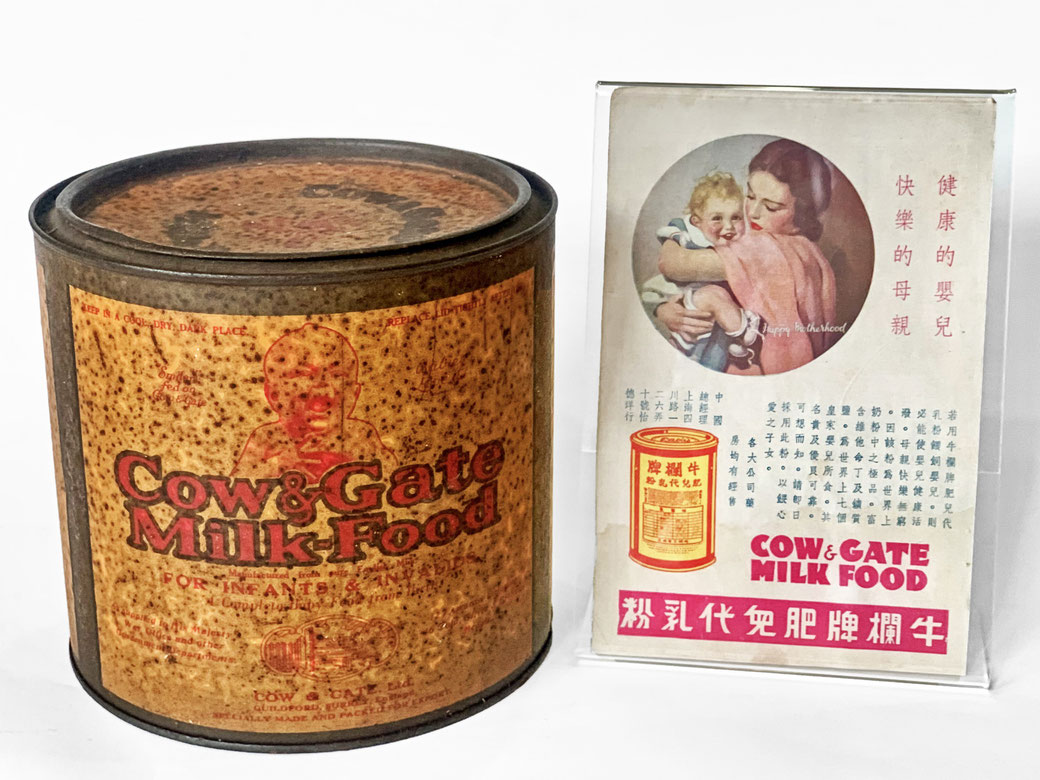

These artefacts from our collection tell the history of an infant formula brand, that by itself would not be particularly noteworthy in China. A 1936 law suit in Shanghai involving Cow & Gate, however reveals the impressive stunts and dirty tricks its ad agency and distributors pulled off…

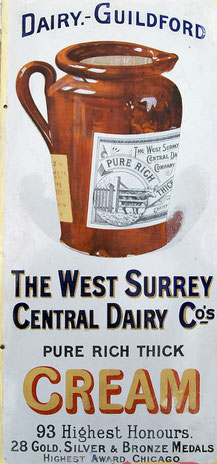

In all fairness, the brand does have a rather funny origin story: In the 1880s the brothers Charles and Leonard Gates ran a liquor store in Guildford. However, in 1885, they were persuaded to join the temperance movement, and hence poured their entire stock into the gutters of Guildford High Street.

Left with no livelihood, they converted their now empty shop into a dairy called West Surrey Dairy, which would expand to baby foods and eventually be named the Cow & Gate company in 1929.

The early logo, created through what the milk jug makers had put on the outside of the company’s distinctive light-brown milk jugs, was described as: "A cow looking uncomfortably through a somewhat untypical four-barred gate, rather as if its neck had got stuck between the bars".

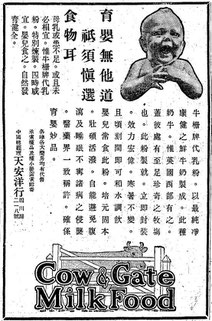

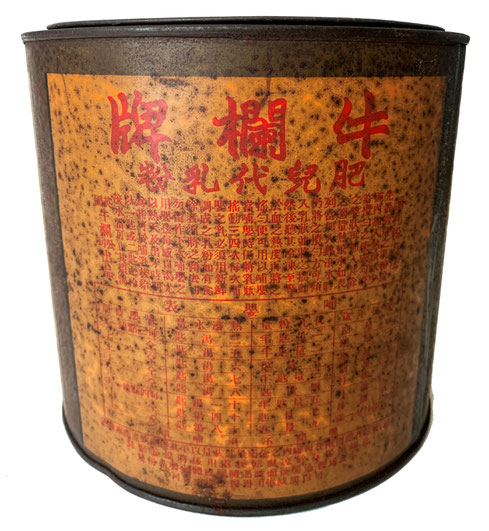

The business however was anything but stuck and already in 1930 made its first foray into China. In that year we can find adverts in China’s largest newspaper at the time, the Shenbao. Import and local sales were handled by Browne, Hill & Company (天安洋行) and they chose Niú zhà pái (牛栅牌) as Chinese brand term, a literal translation of Cow & Gate brand.

Unfortunately, the brand's initial sales were modest at best, and it eventually gave up on further pursuing the market.

The gate to China though opened once again five years later, when the brand attempted another market entry. 1935 was a pivotal year for Chinas economy, when after a period of stagnation and decline, prosperity began to return with a rising GDP.

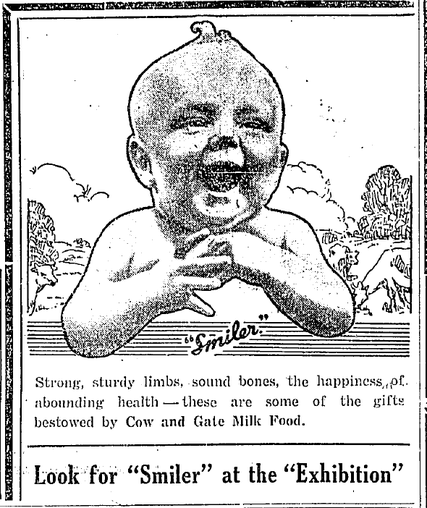

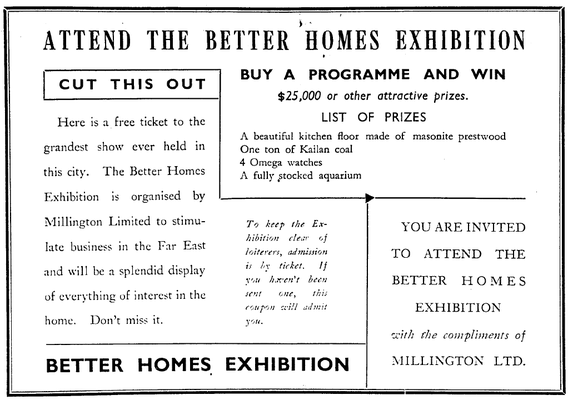

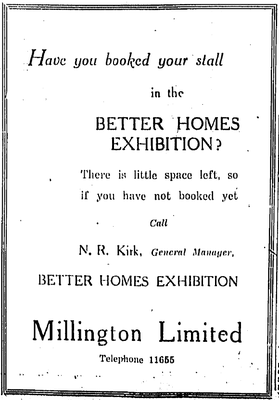

It was during this time that the advertising agency Millington Ltd. pulled off its biggest marketing stunt to date: The Better Homes Exhibition which ran from November 15th to 26th 1935. Located in the former premises of Hall & Holtz on 31 Nanking Rd, it covered 21,000 square feet with 78 stands and created tremendous buzz among both the Chinese and foreign residents of Shanghai alike. Initially planned for 20,000 visitors the show ended up being attended by 70,000 people. On the Sunday of the opening weekend alone over 10,000 visitors stormed the exhibition with hundreds turned away.

The participating companies and brands could not have hoped for a better outcome. One of them was Cow & Gate. Millington, being a British agency, seemed to have lured Cow & Gate at the last minute to attend and also helped organize a new Chinese distributor by the name of Frost, Bland & Company (德康洋行).

However, this second attempt to enter the market was hastily executed, as evidenced by the fact that only 21-year-old E.O.S. Christensen was put in charge of the account. The partnership with Frost, Bland & Company lasted only a few months, and in February 1936, a Cow & Gate sales representative from the UK arrived in Shanghai and terminated the contract.

Instead, yet another firm, H.C. Dixon & Co (怡德洋行) was appointed as new sole agency. They slightly modified the Chinese brand name to Niú lán pái (牛栏牌), which sounds smoother and translates to cow & fence, rather than gate.

This is where things got interesting and led to the aforementioned lawsuit because Dixon & Co.'s first order of business was to poach the young Christensen from Frost & Bland. He willingly agreed and terminated his employment with the firm to continue to work with Cow & Gate at his new job. When the previous employer got wind of what had happened, they refused to pay the one-month outstanding salary for Christensen, which led him to file the claim at court. In the heat of the hearing Christensen among others spilled the beans that his former employer received a 15$ “commission” aka kick-back from the advertising agency (presumably Millington Ltd.) for a billboard advertisement on Bubbling Well Road (today’s Nanjing West Road). It may come as no surprise that in the advertising industry, poaching competitors’employees and receiving kick-backs from agencies or publishers were just as common practices then as they are today, almost 100 years later.

Cow & Gate's story in China came to an end in the late 1930s, as did most other Western brands. The Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 put a halt to trade outside of the international settlements. And when the Pacific War broke out in 1941, Cow & Gate was forced to withdraw completely from China.

Today, however the country has become the largest market of infant formula in the world and Cow & Gate has once again returned to the fray. Its iconic Chinese Niú lán pái brand, presumably first conceived by Dixon & Co almost a century ago, still resonates with consumers today. The trademark is now owned by Danone and represents one of their top 3 brands in China.

Write a comment