Do Chinese people eat cornflakes for breakfast? It turns out, it is as difficult to chew on this question today, as it was in the 1920s. Discover the century-long struggle of Kellogg's in cracking the Chinese market and where the company and its former partners stand today.

The famous flaked cereal was created in 1894 by John Harvey Kellogg and his brother Will Keith Kellogg in Battle Creek, Michigan.

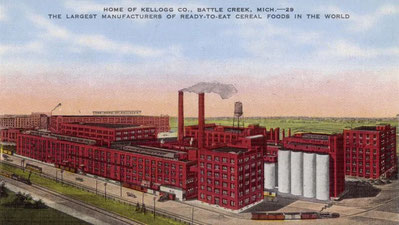

Through innovative advertising techniques and improvements in the quality of the cereals, the company started to prosper at the turn of the century. W.K. Kellogg eventually bought out his brother in 1906 and in 1909 the enterprise was renamed the Kellogg Toasted Corn Flake Company.

By then Kellogg’s cornflakes had become hugely successful and 120,000 cases were already produced per day. In 1914 the company expanded to Canada and Kellogg’s first overseas plant was established in 1924 in Sydney, Australia. The sales representative Joel S. Mitchell, was sent Down Under in August 1925 to launch the brands marketing program there.

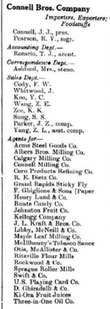

The ambitious young man was likely also the catalyst behind the introduction of the popular breakfast cereal in the Far East: In the very same year, the American food distribution company Connell Brothers, which maintained branches in China, Hong Kong, Japan and the Philippines was appointed sales agent for Kellogg’s.

Two brothers, Morris and John Connell had founded the business in 1895 and setup an office in Shanghai as early as 1898 under the Chinese moniker “Gōnglì” (公利洋行) or “Public Interest” foreign trade firm. Among others it distributed well-known American brands in East Asia such as Carnation Condensed Milk or Royal Baking Powder.

The initial sales strategy of Connell Bros. for Kellogg’s was focused on supplying Western-style grocery retailers in Shanghai, which was considered the most cosmopolitan city in China at the time. In 1926 we can find a first print ad by Van Shing & Co. (万兴食品号), promoting Kellogg’s cornflakes to the foreign population of the Shanghai International Settlement and the French Concession.

This earliest point of sales for Kellogg’s in China was opened in 1920 on the corner of Avenue Joffre and Avenue du Roi Albert, todays Huaihai Lu and Shaanxi Nan Lu. For years it was the largest food store of Old Shanghai.

Starting in 1929, Connell Bros rolled out consumer-focused brand awareness campaigns by placing ads for Kellogg’s in English language newspapers and magazines. Marketed as a “cheery beginning for a busy day” the crisp, crunchy flakes were advertised as a nourishing breakfast dish mixed with cold milk, for children and adults alike.

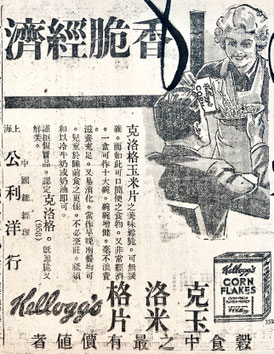

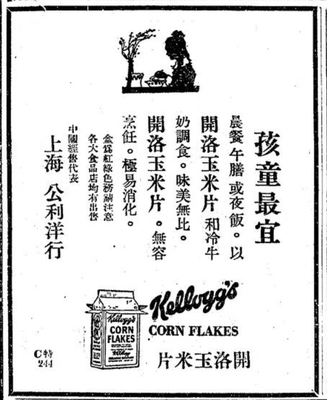

In the 1920s and 30s, as Republican China underwent a period of rapid modernization and westernization, many foreign brands mistakenly assumed that Chinese consumers would quickly also adopt Western food habits. Kellogg's followed suit and launched Chinese-language ads in 1931, using the same positioning and marketing messaging that had worked for them in other parts of the world and for foreign residents in the Chinese outports.

To transliterate the English brand name, Kellogg's initially chose "Kāi luò" (开洛玉米片), which sounded somewhat similar but had no actual meaning.

Alas, by 1934, barely any Chinese were buying the popular Western breakfast cereal, leading Kellogg's and Connell Brothers to assume that maybe the Chinese name was the problem. They changed the brand term to "Kè luò gé" (克洛格), but sales still did not pick up.

It was only by 1936 that Kellogg's and its distributor realized what the actual issue was.

Firstly, Chinese culture is heavily influenced by Traditional Chinese Medicine, which stresses the importance of starting the day with warming foods for good health. Consequently, hot dishes are the norm for breakfast. Secondly, Chinese people historically consumed very little dairy, as the majority of Asian populations are lactose-intolerant. In place of milk, warm soy milk is a popular breakfast beverage.

It is rather perplexing that Kellogg's and its partner Cornell Bros. took so long to grasp this simple fact, when even the famous American advertising guru Carl Crow, had remarked how he “does not believe that any amount of advertising will ever lead to any change in the Chinese diet”, and how “the only foreign food for which there is a steady demand in China is porridge, but that is so much like the native congee, or rice gruel” (which is typically salty and served hot).

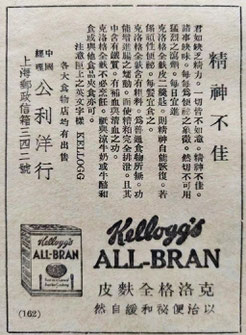

In a last-ditch effort, Kellogg’s performed a rather radical pivot of its China strategy: Instead of Corn Flakes, the company’s All-Bran brand was to be pushed with a strong focus on “health-appeal” in its messaging.

Adverts placed in 1936, touted the high-fiber, wheat cereal as a panacea for “poor spirit and lack of energy”, “containing iron which enriches and purifies the blood” and when “taken with every meal” acts as perfect “remedy for constipation”.

Unfortunately, we shall never know if this flaky scheme to position Kellogg’s as laxative supplement would have ever been accepted by Chinese consumers, as the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 abruptly forced the company to stop all further advertising. Fate proved even less kind when the Communist Party came to power in 1949, slamming the door on foreign enterprises in China for nearly three decades.

Although this did not stop Kellogg’s, from playing on Asian stereotypes in its US advertising such as for the 1950s TV spot, in which the Chinese model “Yum Yum” eats a bowl of cornflakes with her chopsticks. In 2018 a very similar video commercial from Dolce & Gabana, where a Chinese woman clumsily attempts to eat Pizza with chopsticks, provoked wide public outrage in China for perpetuating stereotypes about Chinese culture. A glaring example of the steadfast ignorance of some Western brands, who continue to flounder despite nearly two centuries of collective experience in advertising consumer goods in the Middle Kingdom.

After China began to open up and reform its economy in 1978, it took Kellogg’s over a decade to launch another attempt at the market. The company's first Chinese plant opened in 1995 at Guangzhou. The press release for its launch contained a quote by Arnold G. Langbo, Chairman and CEO, steeped in stereotypical China business jargon: “Reaching a market segment of just 10 percent of the Chinese population, which now exceeds 1.2 billion, would generate a major opportunity for long-term growth.”

It came as no shock to anyone, except Kellogg’s of course, that the notion of a chilled bowl of cereal drowned in milk remained just as foreign to Chinese tastes in the nineties as it had for ages prior. That despite the fact that the company had chosen yet another, admittingly better, Chinese name, now calling itself Jiā lè shì (家乐氏). The Guangzhou factory was eventually shut down and instead, in another attempt, Kellogg’s acquired Zhenghang Food Company Ltd, aka Navigable Foods in 2008. Once more things did not go as planned and the business unit was off-loaded only a few years later.

In 2012 Kellogg’s announced its re-entry to China with its Corn Flakes and Pringles branded snacks under a joint venture with Yihai Kerry Investments Co., Ltd., a subsidiary of Wilmar International of Singapore.

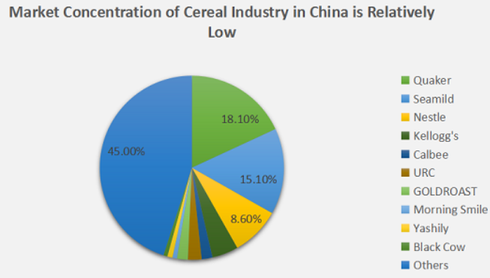

Yet, a decade later, Kellogg's today is still struggling to capture the hearts and stomachs of Chinese consumers, holding only a meager 4.4% share of the breakfast cereal market in China, according to Euromonitor International. To add insult to injury, the entire Chinese breakfast cereal market in fact remains considerably smaller than that of the USA: for 2023 it is projected at US$6.50bn, while in the US it is expected to reach a sizeable US$21.32bn.

Is Kellogg’s ignorance of Chinese culture to blame or was the company simply ill-advised by its partners already from the 1920s onwards? How did those early distributors and retailers fare in China, compared to the Battle Creek manufacturer? In the case of Connell Brothers, rather well: The company was one of the first to resume operations in Asia-Pacific after World War II. Today it is a wholly owned subsidiary of Wilbur-Ellis, a leading U.S. international distribution business with sales over U$3 billion.

For its first old Shanghai retailer, though things did take a different turn: The Van Shing building continued to operate as a grocery store in the Communist era, but was renamed No. 2 Provision Store (上海第二食品商店), and finally demolished in the 2000s. In its place now stands the IAPM luxury mall, which coincidentally houses the well-known C!ty'super import grocery store. Among thousands of foreign products, it also carries a significant range of Kellogg’s-owned brands, such as cornflakes, granola or Pringles potato chips. The symbolic glimmer of hope at this historic location shows, that despite its tainted history, the company may still find success in China through persistence, category expansion and, most importantly, careful localization to domestic customs and tastes.

Write a comment