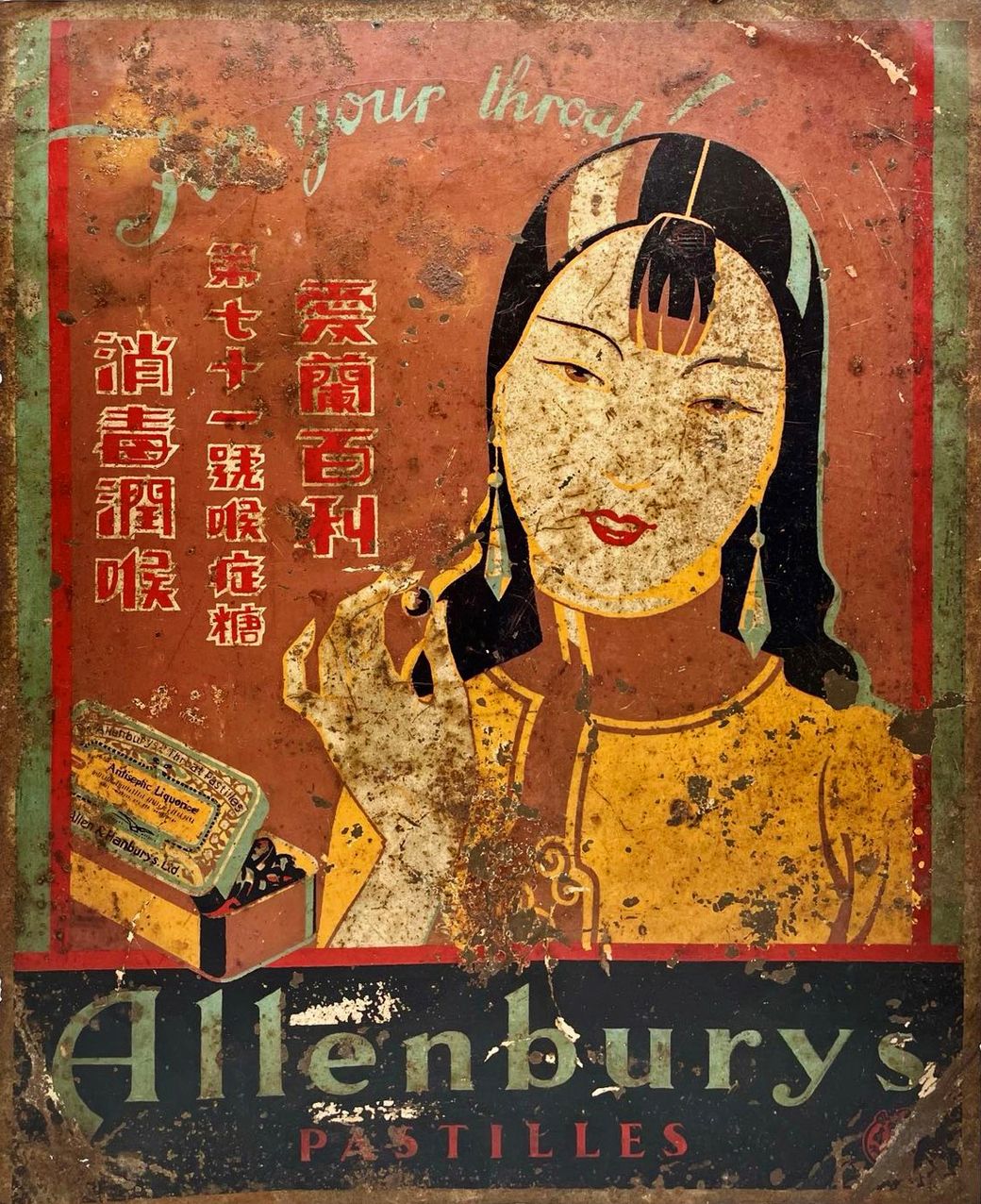

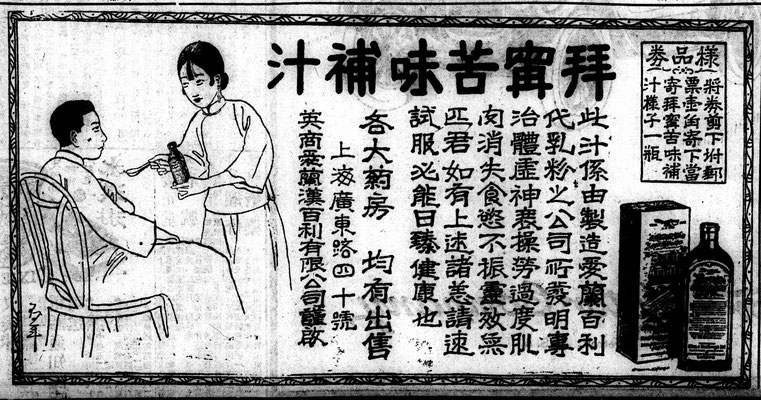

This beautiful mid-1920s Art Deco style advertisement sign for Allenburys tells the astonishing story of the once wealthiest foreign family of Old Shanghai. They were highly esteemed, with numerous schools, two streets, an office building, and even a coffee house named after them. Yet, their name has almost been forgotten, if it weren’t for the rare artefacts that sometimes still show up in the antique markets and the few remnants of their legacy strewn across the vanishing old city.

To unravel their history in China from the exhibit in our collection, we must journey back to London in 1715, when Silvanus Bevan, an apothecary and Quaker, founded a pharmacy in Old Plough Court, Lombard Street. William Allen, also a Quaker, joined the firm in 1792 and rose quickly to become the dominant personality. His wife came from the Hanbury family, who had produced several leading scientists.

Daniel Bell Hanbury joined the pharmacy in 1808 at only age 14 and was made partner in 1824, after which the company was renamed to Allen & Hanburys Ltd. On Allen's death in 1843, the Hanbury family assumed full control of the company. Daniel Bell’s eldest son Daniel Hanbury (1825 – 1875) started work at his father's firm in 1841, in 1857 completed his training in pharmaceutical chemistry and botany and soon took over the leadership of the company. He would turn it into one of Britain’s largest pharmaceutical manufacturers of the time.

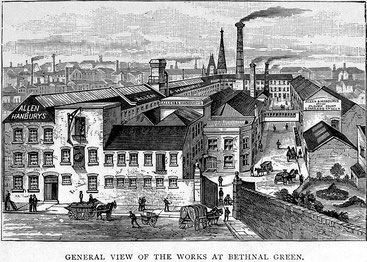

Its factories at Bethnal Green and Ware produced infants' foods, dietetic products, cod liver oil, soap, malt preparations as well as galenical preparations.

Allenburys claimed to be pioneers in the production of pastilles, producing Allenburys Glycerine and Black Currant Pastilles, amongst another 80 different kinds of medicated and crystallized pastilles.

Unlike Daniel, his younger brother Sir Thomas Hanbury (1832 – 1907) did not follow in the footsteps of their father at Allen & Hanburys, but instead sought adventure in the Far East. In 1853 he ventured to Shanghai, which had only opened to foreign commerce a decade prior. In his letters back home, young Thomas remarked that he was “favorably impressed with Shanghai on the whole, though, to speak the truth, it is but a swamp.” With the financial backing of his father and uncle Cornelius, he started Hanbury & Co, merchants in silk and tea. The partnership dissolved in 1857, was briefly restarted as Crampton, Hanbury & Co and then became Bower, Hanbury & Co., which diversified into currency trading and cotton broking. Its Chinese “Hong” name was “Kung-Ping” (公平洋行), which translates to “fair” or “impartial” foreign trading firm. The iconic Chinese name was inherited from another trading firm, G.C. Schwabe & Co, which was absorbed into Hanbury’s company in 1859*.

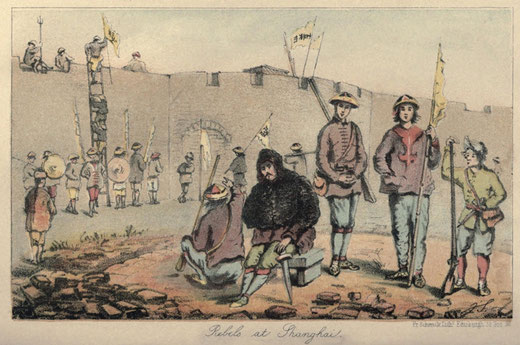

Hanbury arrived in China at a time of widespread civil unrest. In 1854 there were five separate rebellions within the country: the Nien Rebellion, the Red Turban Rebellion (1854–1856), the Miao Rebellion, the Small Swords Uprising and the vast Taiping Rebellion (1850–64), which has been described as the "most gigantic man-made disaster" of the nineteenth century. The Small Swords occupied the Chinese parts of Shanghai and many surrounding villages from 1854 to February 1855. Meanwhile foreign residents of Shanghai lived in self-governing settlements or concessions outside the city walls, in physical and social isolation from the local population.

However, Thomas Hanbury stood out from his fellow British residents in his willingness to immerse himself in the local culture. Hanbury took the unusual step of learning Mandarin Chinese. Moreover, with few single western women in the settlement, and, despite his religious scruples, Thomas would ‘acquire’ a Chinese ‘wife’, dubbed at the time ‘a sleeping dictionary’. Although he maintained the relationship lasted only a matter of months, it was sufficient to produce a son, Ahsu.

Thomas Hanbury (Chinese name 汉璧礼), equipped with his training as botanist and his newly acquired language skills, travelled extensively within China, and soon earned the trust and respect of the local people. He was an essential partner to his brother Daniel, for whose company Allen & Hanburys he helped establish a network of plant acquisition and interchange. Together they mobilized numerous collectors and organized the network to collect specimens, drug samples, and various forms of information and send them to London. The scientific knowledge acquired through this network was instrumental to Allen & Hanburys success as a pharmaceutical company.

Meanwhile, the Taiping Rebellion, led by a religious fanatic, continued to rage on and ultimately caused the death of over 20 million Chinese. However, it also gave Thomas, his next and most important commercial opportunity. With property prices in the international concessions at the lowest point and many thousands fleeing from the rebels and taking refuge in the settlements, he bought and rented out property to the rapidly-expanding Chinese community. As a result and long before the Kadoories, McBains, Sassoons or Hardoons, Hanbury had become the largest private landowner of the Shanghai foreign settlements and extremely wealthy.

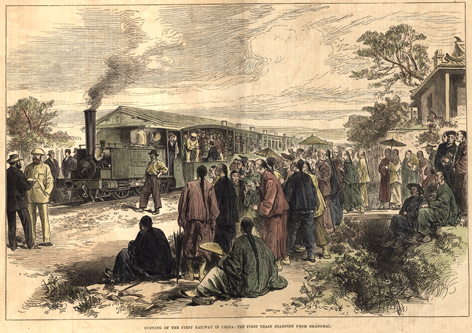

In addition to his work with Kung-Ping and the support for his brother’s company Allen & Hanburys, Sir Thomas was also a pioneer in several other fields: He was a member of the Anglo-American Municipal Council of Shanghai and after the establishment of the International Settlement in 1863, served on the Shanghai Municipal Council. From 1865 to 1866 he was Member of the Commission Provisoire of the French Concession. Furthermore, he was a director of the first railway line to be built in China, the short-lived Woosung Railway and the first telegraph message from Shanghai to Hong Kong was sent from his office.

It was during that time, both Hanbury Road (todays Hanyang Lu) and Kungping Road, located in the Shanghai Hongkew district (today called Hongkou), were named in honor of Thomas Hanbury and his trading firm, respectively.

In 1868 Sir Thomas married Katherine Aldam Pease and they had 4 children.

Besides his business accomplishments, Thomas Hanbury was also a philanthropist, making generous donations to various hospitals, the Shanghai Museum, the Royal Asiatic Society and presented trees from his private property to fill the Public Gardens on the Bund and Bubbling Well Cemetery. Most notably he financed the Children’s Home for Chinese (Thomas Hanbury Home) and the Eurasia School. The five-storey building, was once the highest in Shanghai, commanding ‘one of the most comprehensive views in the Settlement’ and ‘magnificent’ vistas from the attic. The school later moved further north in Hongkou and was divided into separate campuses for girls and boys and renamed to Thomas Hanbury Schools for Boys and Girls.

When Thomas Hanbury finally left Shanghai in September 1871, his Chinese acquaintances and friends brought him so many parting gifts that he had to beg them to stop. He retired a very rich man to Liguria on the coast of north-western Italy, where he built the much-admired Hanbury Gardens at La Mortola. After his departure Bower, Hanbury & Co. was renamed to Iveson & Co. The Hanbury name though remained closely connected to Shanghai. For example, in 1904 the “Thomas Hanbury Coffee House” was opened on Broadway with 50 beds, offering refreshment & lodging for sailors.

Thomas oldest son Sir Cecil Hanbury was born in 1871 in Shanghai and when he returned to the city, the trading firm his father had established once more changed names to Ward, Hanbury & Co. In 1907 it became Ward, Probst & Co and after that in 1911 Probst, Hanbury & Co, although the company always maintained its famous and well-respected Chinese name “Kung-Ping”. As one of the oldest foreign trading firms, it had become a legend in its own right and many influential personalities of Old Shanghai, such as Alfred B. Rex, who was featured in one of our previous stories, or famous architect C.H. Gonda launched their careers there.

Thomas second son Horace eventually also moved to Shanghai and became a partner in the firm. Together with his brother the Hanbury’s lived at the family residence “The Haven” on 65 Sinza Road (now Xinzha Lu).

Meanwhile Allen & Hanburys, the company of Thomas’ brother Daniel prospered and expanded internationally with overseas branches in Lindsay, Ontario, Durban, India, Australia and Buenos Aires. Supported by Thomas Hanbury it had also made first forays into China, where since the 1860s the company supplied imported medicines to local hospitals. In 1912 Allen & Hanburys formally entered the market and established its own subsidiary in Shanghai (爱兰汉百利有限公司), although it primarily still sold to Western consumers and local institutions. Only after the First World War and during the boom of the 1920s did the firm start advertising and selling to Chinese consumers on a broader scale. We can find a myriad of print ads in Chinese newspapers emerging and also the Allenburys metal advertising sign from our collection dates back to that era.

The Hanbury’s trading business Probst, Hanbury & Co likewise continued to grow in China and in 1921 erected its headquarters, called the Kung-Ping Building, on 21 Jinkee Road (later re-numberd to 81 and famously the location of advertising man Carl Crows last office).

Only 9 years later though, in July 1930, the business was wound up**. Interestingly, the reason for the dissolution was not due to financial issues, but rather because the partners had retired. This indicates that Thomas Hanbury's heirs did not depend on the company for their livelihood, but rather chose to keep it as a passion project and a symbol of tradition.

Allen & Hanburys still sold Allenburys in China until the Communist Revolution in 1949. In 1958 the global business was absorbed by Glaxo Laboratories. Its successor company, GlaxoSmithKline, used the Allen & Hanburys name for the specialist respiratory division until phasing it out in 2013. In 2021, the name was trademarked in the United States as part of the formation of Allen & Hanburys Inc., an American pharmaceutical and consumer products company focused on Pediatrics, Dermatology and Respiratory Care. Even the Allenburys brand name was revived in recent years for soaps manufactured by Boyd Pharmaceuticals from Canada.

You might wonder what happened to the delicious Allenburys pastilles. It turns out even they do live on, but under another name: In the early 1930s, the Basel-based company Doetsch Grether AG secured the distribution rights and firmly established the traditional product on the Swiss market. After completely taking over the Allenburys Pastilles brand and transferring production to Switzerland, the brand was renamed Grether’s Pastilles in 1974, which also led to the logo and the tin being modified.

Although Probst, Hanbury & Co was discontinued in the 1930s, it did not mark the end of its Chinese name and legacy in Shanghai: Kungping Road (now called Gongping Lu) still exists to this day and so does the old Kungping building on Dianchi Lu (the former Jinkee Road).

Even the campus of the Thomas Hanbury School for Girls still exists and is now the location of the Shanghai Shixi High School.

* The firm was originally founded in Shanghai in November 1843 as Boustead, Schwabe & Co., which in 1850 became Sykes, Schwabe & Co.

** The Hong name Kung-Ping did in fact not end with Probst, Hanbury & Co but was passed on to its successor company White & Co, Ltd. W.A. (founded by W.A. White, the former Managing Director of Probst, Hanbury & Co) which, except for during Japanese occupation, continued to be in operations until at least 1947. This made the name Kung-Ping in use for more than 100 years and one of the very first and longest standing foreign trading house names before the Communist Revolution.

Write a comment