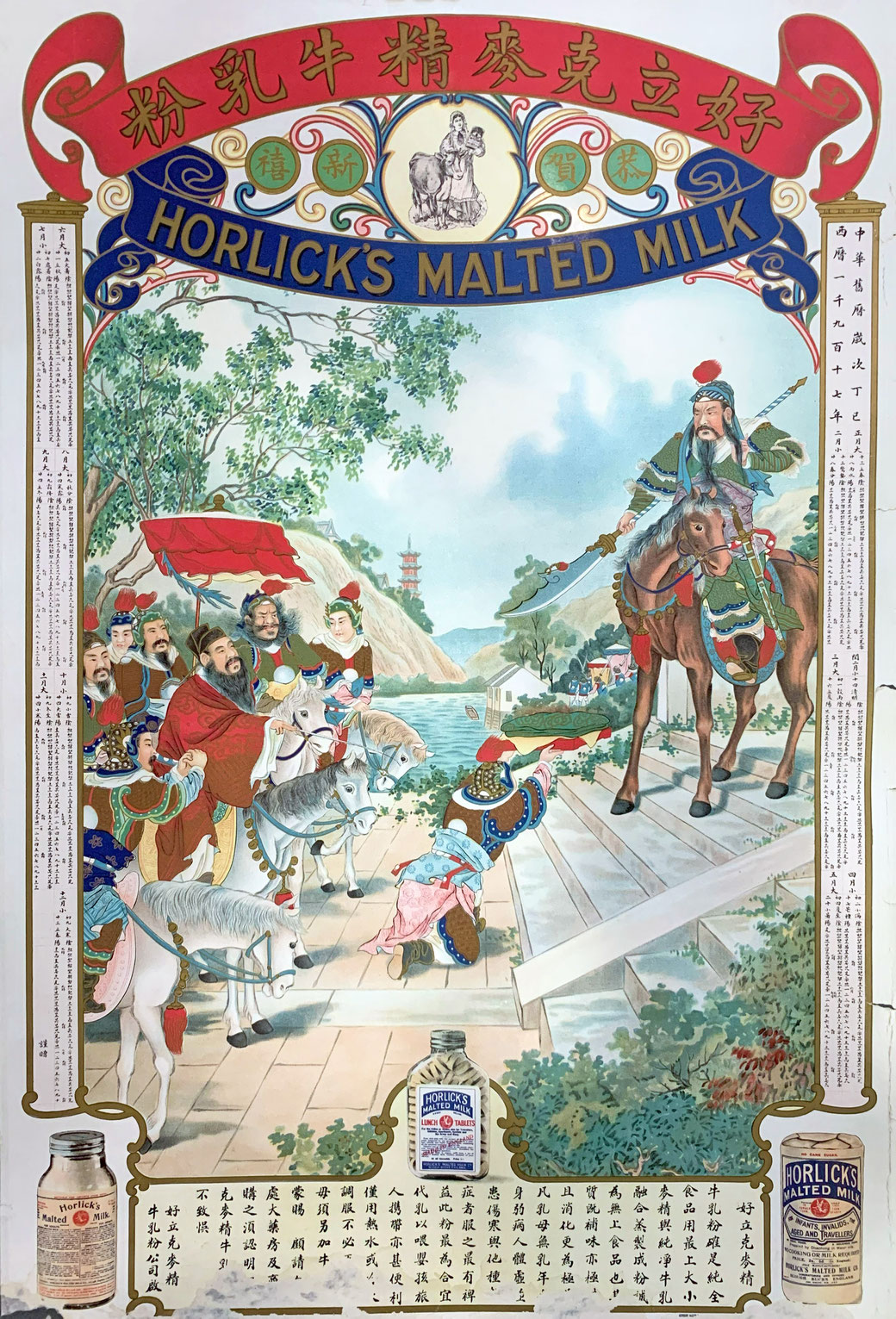

This unique 1917 Horlick’s calendar advertisement from our collection depicts a martial scene that actually takes us all the way back to the Three Kingdoms period of Chinese history. Get ready for an immortal story about the mightiest of men, war, loyalty and... warm milk.

Sweet, Sweet Milk for Infants and Invalids

When you hear “malt”, you probably would think of it in the context of brewing beer or distilling whiskey. Depending on where you are from, you also know it as a hot drink for children or as a treat consumed in a traditional café or tea restaurant.

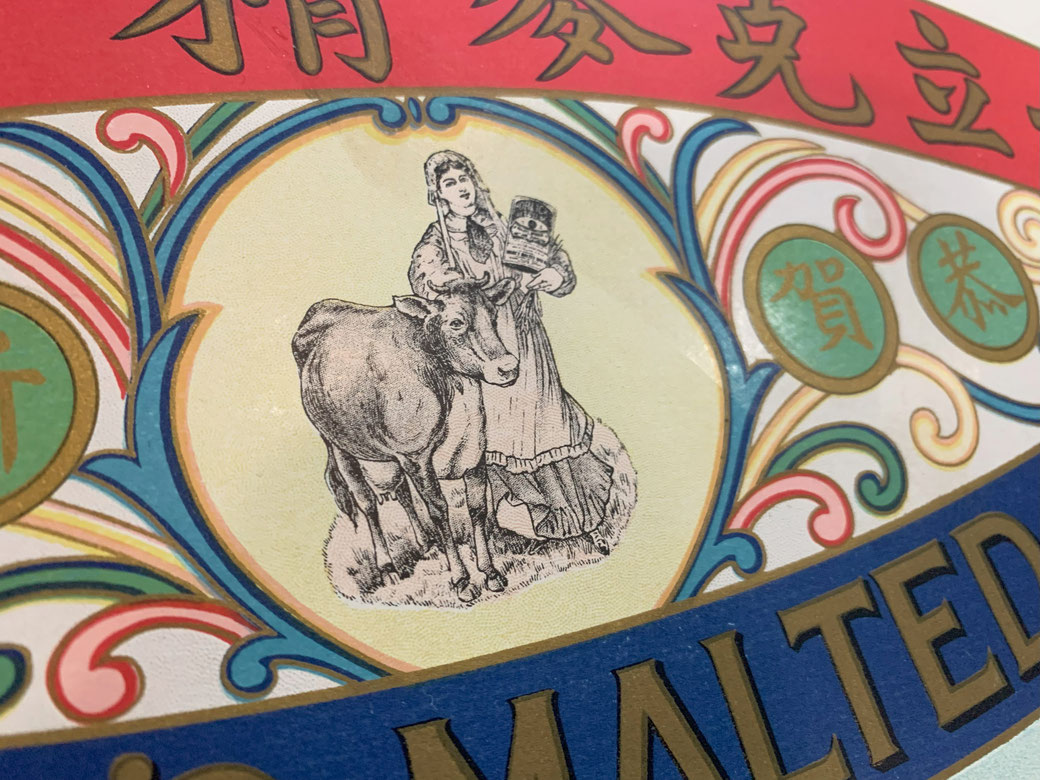

Horlick’s, developed by the eponymous brothers James and William Horlick, is the brand mostly closely associated with this sweet type of malted milk beverage. Originally from England, the brothers emigrated to Chicago, USA, and in 1873 started marketing their creation "For The Infants, Invalids". Trumpeting the medicinal properties of one’s beverage product was a big thing at the time. They soon added the “aged and travelers” as afflicted groups that could significantly benefit from ingesting warm milk. In the early 20th century, it was sold as a powdered meal replacement drink mix in the US, UK, and many parts of the British Empire.

Horlick's in China and The Great War

In Mainland China we first hear of Horlicks in January 1897, when the North-China Daily News reports, that they have received “from Messrs. Bennett & Co, a bottle of Horlick’s Malted Milk, which has a pleasant taste and is specially recommended as food for infants, invalids, and the aged”. Ah, the golden days when newspapers still reprinted press releases word for word — which never happens today. (Still, we have to say, the good-faith tone of the North-China Daily News report is pretty disarming… )

In around 1904, distribution was first handled by Dunning & Co, then in 1909, the newly formed Dutch trading firm F.A. Van der Loo & Co (文达罗洋行) took over as general agents. From that year on until the beginning of World War I, we can consistently find a heavy advertisement campaign in Chinese newspapers for Horlicks under the Chinese name Hǎolìkè (好立克), the very same term the brand still uses to this day.

The Great War temporarily stopped exports to China but saw extensive use of Horlick’s in The West and, specifically, at the front, boosting its awareness around the world. Already in 1916, the company restarted its advertising and sales efforts in China, and it appears that for the first time, they also utilized calendar poster advertisements.

Nothing Sinister Happening Here: Horlick’s Calendar Advertisements

A short article from 27 February 1916 in the China Press, mentions that the newspaper has received the new calendar of the Horlick company — big news indeed — intended for Chinese circulation. According to the report, the calendar featured a scene of “two Chinese youths with axes in their hands going up to the side of a mountain to call on two maidens”. As you do. The news report continues to state that, much to the purported relief of their readers, we’re guessing, “The axes can’t be for any sinister purpose because of both the young ladies are smiling.” Scandal averted. It’s an entirely consensual axe-wielding, malt milk-drinking session.

It is unclear (at least to us…) which scene from Chinese history or mythology this 1916 calendar may have depicted, but we are delighted to offer a more precise interpretation of our 1917 edition.

The key visual shows the warlord Cao Cao saying his goodbyes to general Guan Yu at Baling bridge during the time of the Three Kingdoms in China and there’s a bit to unpack here with the backstory.

Guan Yu was the sworn brother to Cao Cao’s archenemy Liu Bei, but when the latter’s wives were captured by Cao Cao, Guan Yu surrendered to him under the condition of safety for Liu Bei’s family. A second condition for the surrender was, that once Liu Bei had re-organized his forces, Guan Yu could return to him. Cao Cao accepted these terms and treated Guan Yu respectfully. Guan Yu served under Cao Cao, who tried to coax him to his side permanently with gold, titles, and prized horses. A weaker man would have easily given in, but Guan Yu took the first chance to return to Liu Bei and fight alongside him, proving his loyalty. …For the ages, as it turned out.

God of War and Loyalty, and Noted Imbiber of a Nice Mug of Hot Milk?

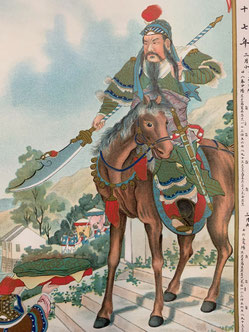

In Chinese art, Guan Yu traditionally wears a green robe and is portrayed as a red-faced warrior with a long, lush beard and trusty, double-edged Halberd-style blade in his hands.

You can see him located on the right side of our poster.

Behind him we can also spot the carriage carrying Liu Bei's wives on their escape.

Cao Cao on the other hand, is typically depicted with a red overcoat and a Han Dynasty-style authoritative hat granted by the Emperor. We can find him on the left side of the image, surrounded by his retinue who are seen paying their respect to Guan Yu.

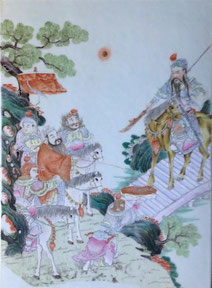

In the center we see one of Cao Cao’s soldiers gifting a silken coat to Guan Yu to commemorate the bond the two men shared.

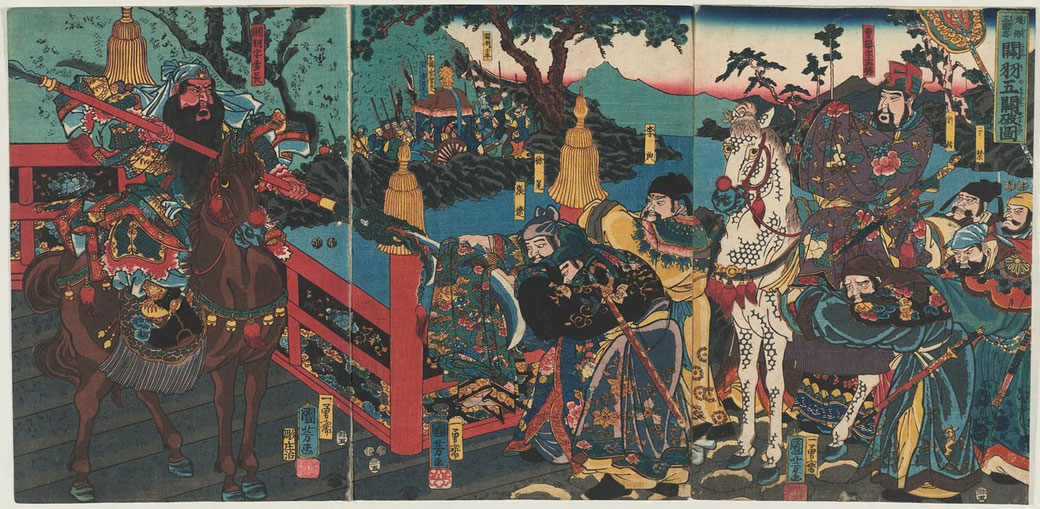

This classic scene was interpreted by many artists over the years, most famously in a Japanese woodblock print from 1853, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi titled “The Records of the Three Kingdoms: Guan Yu Defeats Five Barrier Points”.

The illustration on our poster, however, more closely resembles the composition of a late Qing-Dynasty or early Republican porcelain plaque of the scene.

After his death Guan Yu was romanticized in popular lore, in drama, and especially in the Ming dynasty novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms”. Ultimately, he was canonized as God of War and Loyalty —protector of China and of all its citizens.

The mighty Guan Yu was reported to celebrate the deaths of his enemies with warm wine. It is however quite unlikely, that the man’s legendary strength, moral fortitude, and military acumen stemmed from mugs of American hot malted milk…

…but history doesn’t specifically weigh in on it, so we’re going with a hard maybe not.

How to Get Ahead Selling Milk to a Lactose-Intolerant Nation

In fact, milk was uncommon in China historically, with a large part of the population being genetically lactose-intolerant. Likewise, malt was unknown for its usage in drinks, except for the aforementioned production of beer. It is thus no surprise that in the early 20th Century, both Horlick and its competitor Ovaltine struggled to introduce their product to Chinese consumers, who much preferred traditional soy milk. The same was the case for Quaker Oats or Cadbury’s Bournville cocoa, who’s misadventures in China we both previously covered.

Today still, China has one of the lowest levels of per capita milk consumption in the world — a fact that even Guan Yu, the great holy deity of war, supporter of peace, and promoter of morality and righteousness, could not overcome.

Nonetheless, out of these famous four cautionary case studies of milk-based drinks or cereals, Horlick’s was the most successful and continued to advertise heavily throughout the 1910s and 1920s, despite its overall disappointing sales.

The company also kept issuing colorful poster advertisements annually and in 1925 the English-language press in China blessed us with yet another hilarious art review of the latest Horlick’s calendar – but you can read that for yourself.

Horlick's Malt Milk: The Magic Cure for “Night Starvation” (What?)

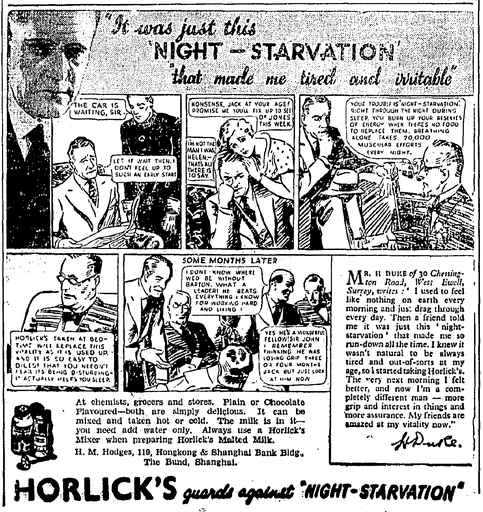

Despite the ramp-up in advertising activities in the previous decade, it was not until 1931, however, that Horlick’s discovered the happy coincidence that their product was, in fact, a cure from something called, “night starvation”.

This fortuitous development came in the tenure of their new general agents, Hodges, H. M. & Co (霍傑士洋行), who had taken over in 1927.

A mysterious ailment, “night starvation”, could be treated, luckily enough, with a nice hot mug of malted milk right before bedtime. The new marketing strategy was soon introduced to China and local advertisements became more professional and diversified, targeting groups beyond “infants” and “invalids”, night starvation, being a somewhat universal condition.

They began seeking the patronage of white-collar workers, fragile and young single women seeking suitors, busy housewives, overworked husbands, mothers concerned with their child’s development — anyone with stress in their lives. Which is, of course, everyone.

Everyone has night starvation, as it turns out. Luckily there is a cure!

Starting in 1935 the company rolled out a new print advertising format with short comic strips, addressing these different target audiences. Besides its strengthening qualities, Horlicks was now specifically advertised as a sleeping aid when consumed as a hot drink at night, following the global success of their “night-starvation” campaign. It was furthermore promoted as a remedy against colds and even as a coffee alternative — coming full circle there.

Horlick's the Everything Aid and Another War Comes Around

It is unclear which advertising agency Horlicks used in China at the time, but in 1935, the brand participated in the Shanghai Better Homes Exhibition, organized by the British agency Millington Inc, which may have also had Horlicks as an account for other marketing activities.

Either way, the brand continued to advertise throughout the ‘30s with sales continuing to rise.

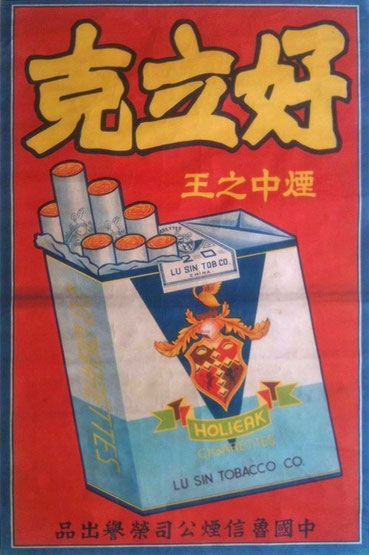

The outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, alas, stopped sales for Horlick in China entirely. Not only that but shortly after the Japanese occupation of all of Shanghai, including the International Settlement, a copycat cigarette brand by the English name of “Holieak” emerged on the market; also a cure-all sort of product depending on your perspective… one way or another, of course. To add insult to injury, they used the identical Chinese characters as Horlick to market the product.

After the war in 1945, the original malt drink brand did make a short comeback, now advertised as a “lǎo pái“, a famous “old brand”, but never returned to its pre-war levels until in 1949, when it left the Chinese mainland market indefinitely. Horlick’s popularity gradually declined in the US and the UK in the 1960s, but it remained a widespread nutritional supplement in developing economies, where people struggled with sufficient calorie intake, ironically making it far more popular in countries like India than the brand ever was in its countries of origin.

The Famous Old Brand Today

Today, Horlick is produced by the Anglo-Dutch company Unilever, and while it is no longer officially sold in Mainland China, it remains a popular beverage in Hong Kong as a historical curiosity. In tea restaurants and diners of the former British colony, Horlick continues to be cherished as a café drink, that can be served hot or cold and is usually sweetened with sugar. Call it a coincidence, but also Guan Yu, still features prominently in the city’s popular culture, from the famous Young and Dangerous film series to video games and TV dramas. Shrines to him are commonly found in restaurants and shops.

The spirit of Guan Yu, however, is symbolic of victory against the odds, winning unwinnable battles, and never giving up. Maybe this is something Unilever might consider if they ever plan to introduce their heritage beverage to the Mainland again.

Write a comment