The Eagle Brand can be traced to 1856, when Gail Borden introduced condensed milk as the flagship product of his newly formed dairy company. In Asia the brand was licensed by the Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company and, in 1874, became the first registered trademark in the then-British colony of Hong Kong. On the mainland the "Fēiyīng" (飞鹰) brand was protected by a “proclamation issued by the Taotai in the ninth moon of the thirtieths year of Kuang Hsü”, meaning the trademark system of the late Qing Dynasty in Beijing in 1904. A Nestlé sales office was opened in Shanghai in 1908 and, by the 1920s, The China Weekly Review had written "there aren’t many places in China where one cannot find Eagle Condensed Milk today” – an amazing achievement in the eyes of the Western powers and absolute market dominance secured for the Anglo-Swiss manufacturer in the Middle Kingdom.

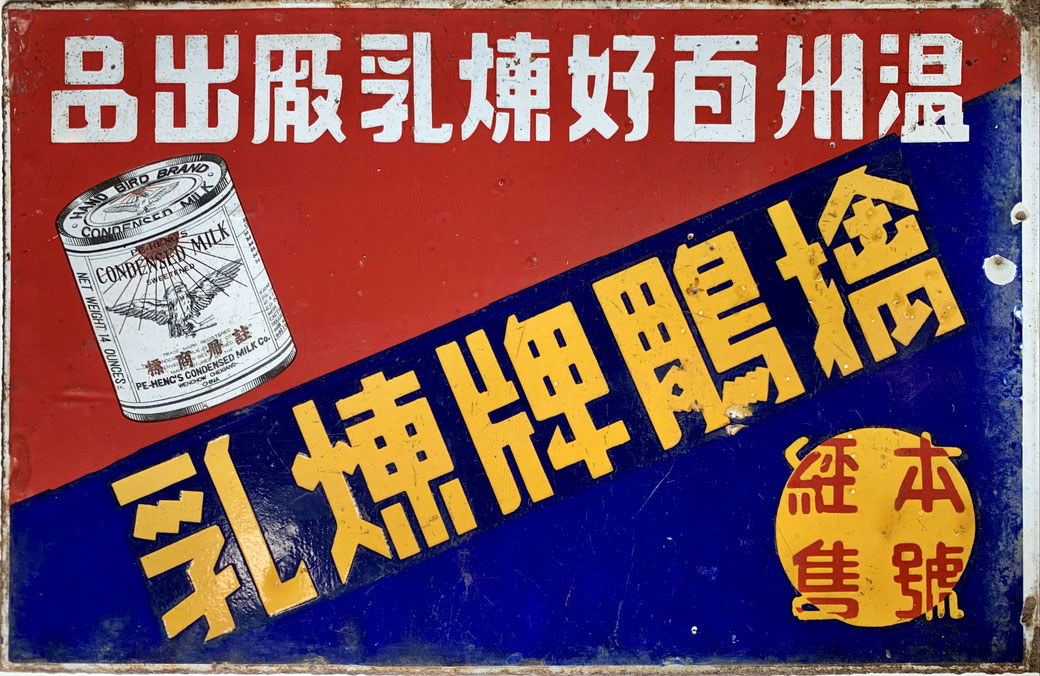

At first glance the enamel sign from our collection, it could very well be mistaken for an advertisement of Gail Borden’s Eagle brand. The resemblance of the overall tin can design tobthe eagle logo it prominently features is uncanny. Only upon closer inspection and decipherment the Chinese brand name, do we realize it is actually for Pei-Heng’s “Hand Bird” brand or "Qíndiāo" (擒雕牌), which translates to captured eagle or vulture in Chinese.

Lacking the historical context, Pei-Heng’s brand would, especially from a Western perspective, immediately be dismissed as a blatant counterfeit, a misleading forgery or a copy-cat brand at best. While it is certainly true that China has created many an unabashed knock-off brand throughout the close to 200 years of direct trade relationships with the West, the backstory of the "Captured Eagle" is far more nuanced. And, rather than a story of a frivolous business decision for quick profit, it is a story that shows some of the events and motivations that justly defined Chinese entrepreneurs in their relationship with the West .

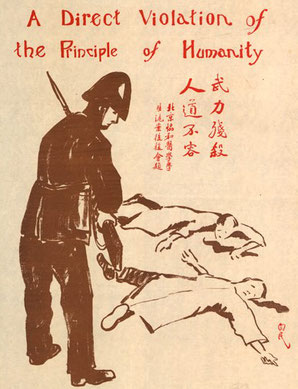

Inspector Edward Everson pulled out his pistol and pointed it at different people in the front ranks of the crowd. Close to 2,000 protesters were estimated to have gathered in front of the Louza Police Station that day, May 30th, 1925. “Ding, veh ding-ts-meh iau tang-sah”! he shouted in Shanghainese, then once more in English: “Stop! If you do not stop, I will shoot!”. A few moments later his bare-bones staff of only two dozen officers opened fire and left nine protesters dead on the ground. Fourteen more were hospitalized with many others left wounded.

The protest had arisen when a Japanese foreman shot and killed a Chinese worker in a Japanese cotton mill, subsequently escalating to an uprising against foreign enterprises across Shanghai. The bloody incident which became known as the “May 30th Tragedy”, shocked and galvanized China. The strikes and boycotts, coupled with further violent demonstrations and riots - labelled the "530" Movement - quickly spread across the country, bringing foreign economic interests to a near standstill. Only by November, when Chiang Kai-shek secured his power after Sun Yat-sen’s death, did the strikes and protests begin to fizzle out. To this day, the massacre is regarded by Chinese scholars as one of the most important events in modern Chinese history and, like the May Fourth Movement in 1919, constitutes a crucial turning point in Chinas attitudes towards the Western world.

Not only did the May 30th Movement trigger nationwide boycotts of Western products, it also encouraged thousands of entrepreneurs across China to develop domestic brands, thus filling gaps in supply and developing national industries after over 80 years of humiliation since the unfair treaties imposed as result of the Opium Wars.

One of them was Wú Bǎihēng (吴百亨), a native of Wenzhou in Zhejiang province who started his dairy factory Ruì'ān Bǎihǎo (瑞安市百好乳业有限公司) in late 1925 as an immediate response to the May 30th Tragedy.

Its hero product, the Captured Eagle brand, was a direct attack on the Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company, with a clear message to domestic consumers: the foreign eagle shall no longer fly freely in the Chinese market.

After the establishment of the Nanjing National Government, a circular was issued in the name of the National Trademark Registration Office at the end of 1927, requiring all foreign businesses to reregister their trademarks that had previously been filed with the Beijing government, before May 1, 1928. Evidently, Nestlé and its lawyers either overlooked this change in policies or missed the deadline, allowing Wu Baiheng to secure his “Captured Eagle” trademark together with the emblematic logo on March 2, 1928, when it was published in Volume 956 of the “Trademark Gazette”.

Over several years and into the mid-1930s Nestlé fought in the courts to appeal the decision but was rejected each time. As a last resort the Anglo-Swiss company proposed to purchase the Captured Eagle brand for "100,000 silver dollars”, knowing well that a bird in one hand is worth more than two competing in the bushes, but the proud Chinese Wu Baiheng rejected the offer outright. The two brands were forced to coexist and battled fiercely over market share until the escalation of the Sino-Japanese War in 1941, when both ceased operations in China.

After the 1949 revolution the Baihao factory resumed work in 1950, and its Captured Eagle brand became an iconic product for many Chinese born in postwar China and up to the 1980s, when foreign condensed milk brands started to enter the reformed market again. In fact, the Captured Eagle brand, or “Qindiao” exists to this day and is sold across China through a joint venture of Baihao and the stock listed Shandong Panda Dairy Co., Ltd. Likewise, the original Eagle brand by Borden, including its licensed version by Nestlé, continues to be sold in China and across the world and it remains the uncontested leader in the global condensed milk category.

Write a comment