Tiger Balm is one of the most recognized Chinese brands in the world, yet few know of its international origin story, its eccentric founders & that at one point it was even banned in China. Let's take this 1930s ad from our collection to explore the famous ointments history.

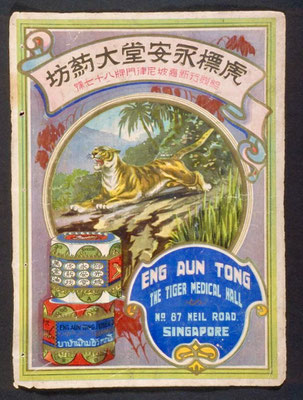

The origins of Tiger Balm trace back to the 1870s in Rangoon (now Yangon), Burma, where Aw Chu Kin (胡子钦), a Chinese herbalist from Fujian Province's Yongding County, established his apothecary. Chu Kin had emigrated from China in the 1860s to help his uncle's herbal shop, eventually founding his own business called Eng Aun Tong (永安堂), meaning "Hall of Everlasting Peace".

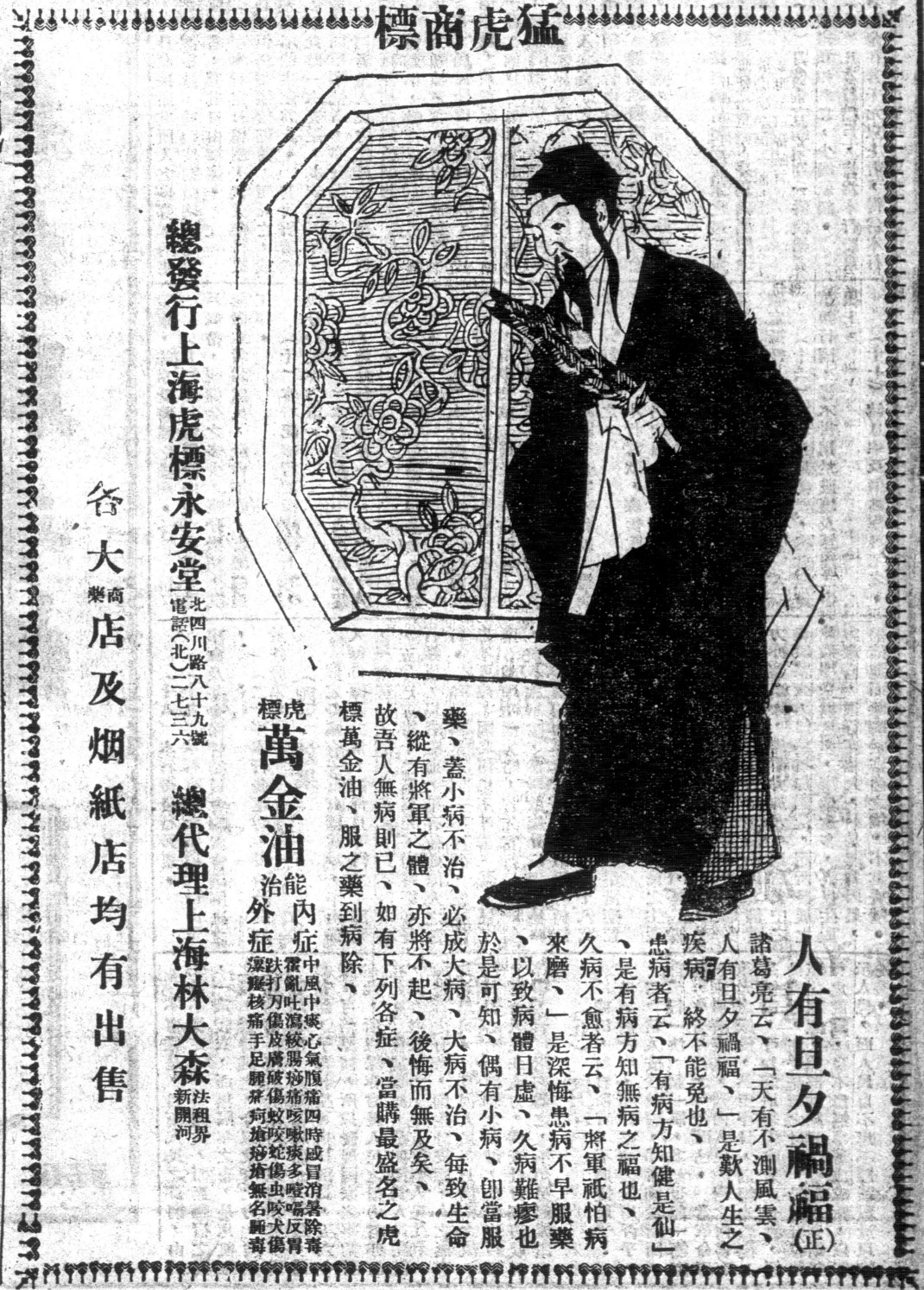

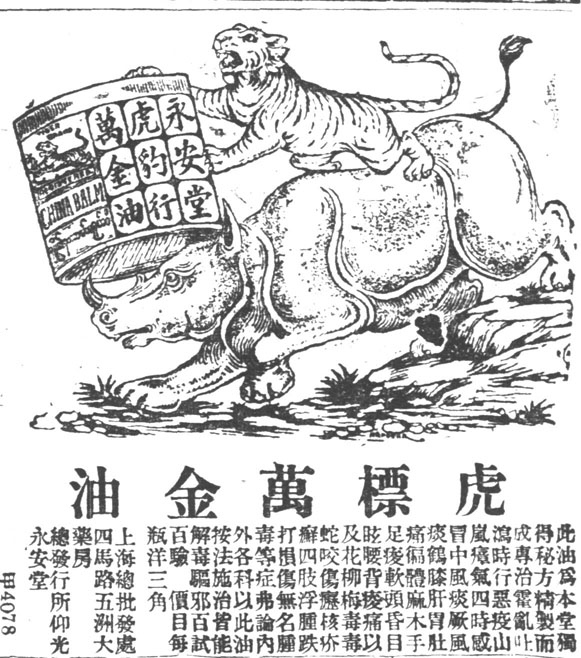

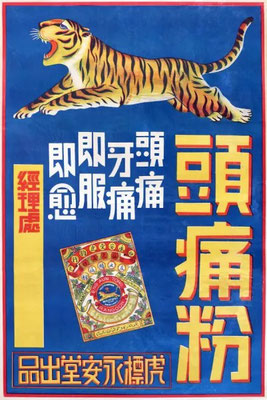

The precursor to Tiger Balm was originally called Ban Kin Yu (萬金油), literally "Ten Thousand Golden Oil," which Aw Chu Kin developed using traditional Chinese medicinal formulas.

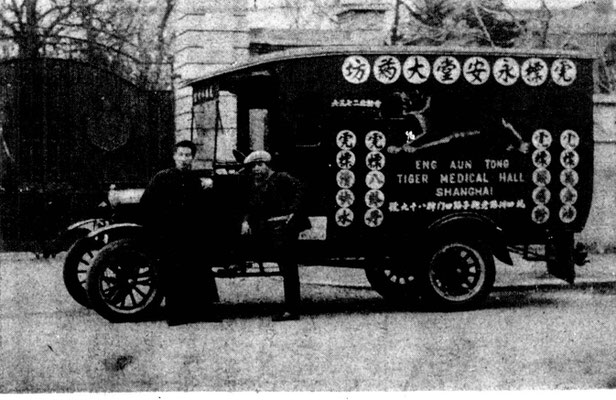

From ads in newspaper archives it seems that already in the late 1800s Eng Aun Tong had set up a small subsidiary in Guangzhou China and in 1896 a pharmacy shop in Shanghai.

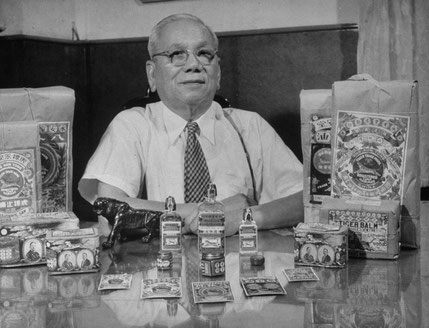

When Aw Chu Kin died in 1908, he left his business to his two sons: Aw Boon Haw (胡文虎, meaning "gentle tiger") and Aw Boon Par (胡文豹, meaning "gentle leopard").

The brothers, who had different educational backgrounds - Boon Haw educated in traditional Chinese medicine in China, and Boon Par in Western medicine in British Burma - combined their knowledge to perfect their father's formula.

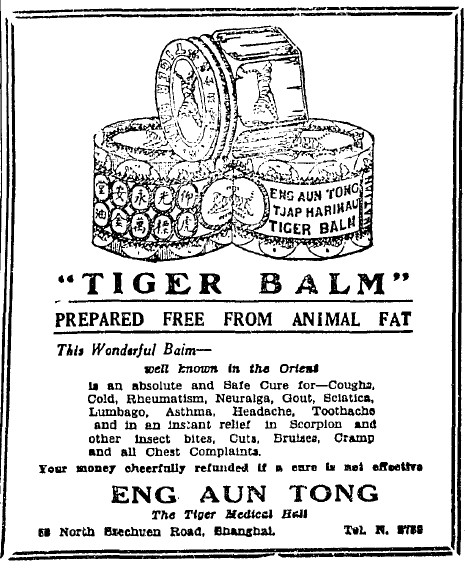

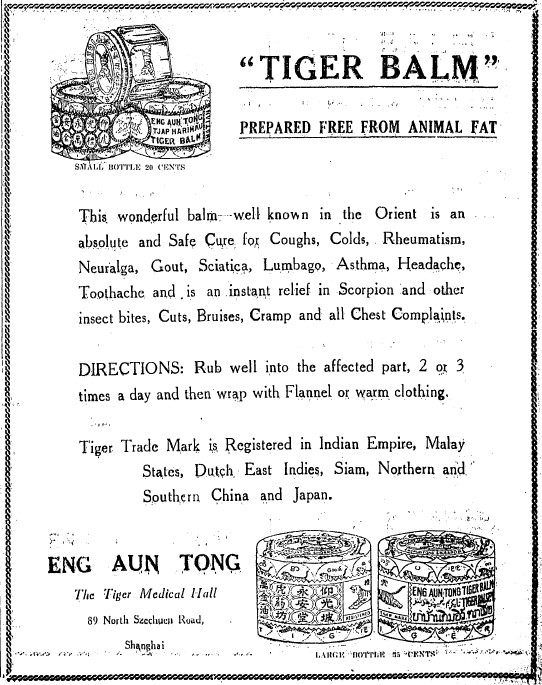

By 1918 when the brothers had become some of the wealthiest business people in Rangoon, they refined the product and renamed it "Tiger Balm" after the elder brother Boon Haw, whose name contained the Chinese character for tiger. The tiger also served as a powerful marketing symbol, representing strength and vitality in Chinese culture.

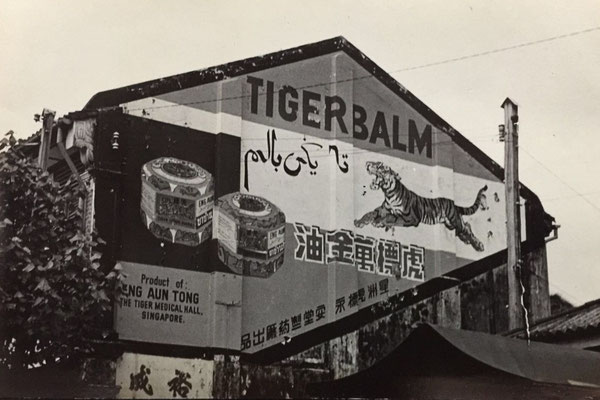

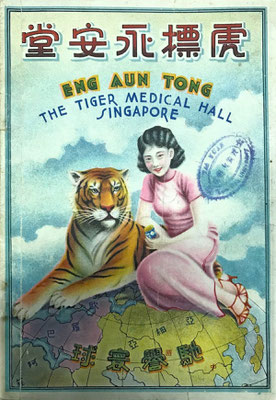

In the 1920s, the Aw brothers moved their operations from Burma to Singapore, establishing a larger factory with production capacity ten times greater than their Rangoon facility. From Singapore, they built an extensive distribution network across Southeast Asia, with Tiger Balm quickly expanding its popularity in Burma, China, Japan, and throughout the region. The product gained significant popularity in Mainland China, initially mostly in the southern coastal regions, but by the early 1930s Eng Aun Tong branches were established in all major Chinese cities.

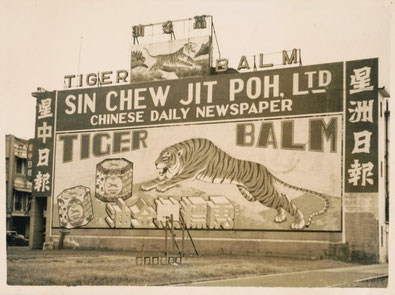

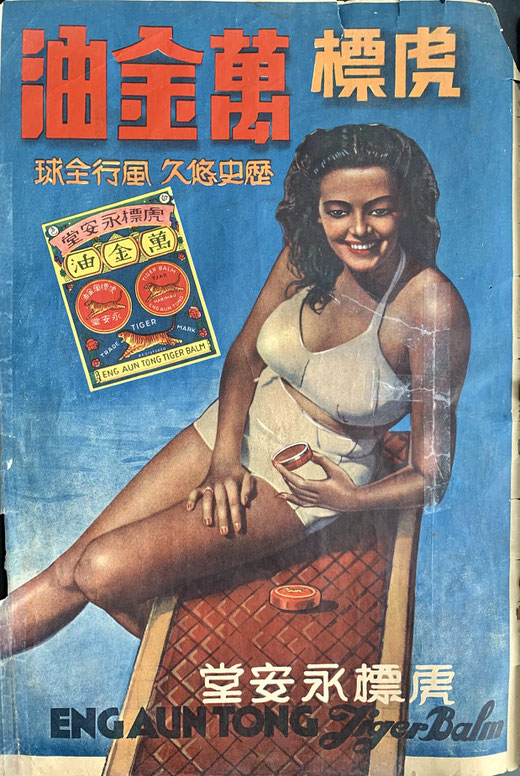

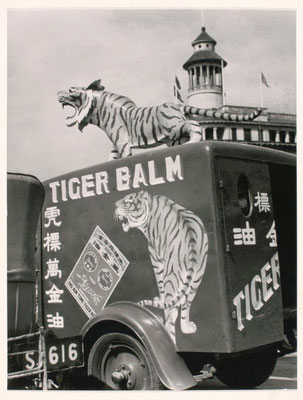

It is during this time period that massive advertisement campaigns were rolled out across the country incl. billboards, flyers, vehicle advertisements and of course print adverts. Over 22,500 ads for Eng Aun Tong can be found in Chinese newspaper archives from the 1920s to 1940s.

Soon Aw Boon Haw, who was the more dominant of the two brothers, realized that he spent so much money on advertising that "he thought it would be cheaper to just open a few newspapers”. Within the next 30 years, he indeed built a vast media empire to support Eng Aun Tong’s marketing efforts. Between 1929 and 1951, Aw Boon Haw established 17 newspapers across Asia, including several in China Mainland such as the “Xinghua Daily” (星华日报) in Shantou, the “Daily Star” (星光日报) in Xiamen, and plans for the “Xinyue Daily” (星粤日报) in Guangzhou.

After establishing his own newspapers to promote Tiger Balm, Boon Haw came up with even more creative marketing ideas that were almost unheard of in his time. One such tactic was converting his stable of cars into „Tiger Cars“, which attracted plenty of attention wherever he went, and typified his flair in promoting his business. Each car was painted with tiger stripes, a tiger head with whiskers and fangs covering the radiator, red bulbs for the tiger’s eyes, and even the sound of the horn resembled a tiger’s roar.

Besides his cars Boon Haw’s eccentric personality and immense wealth was exemplified by his four wives and countless concubines, as well as by his ostentatious 18-karat gold spectacles - not worn due to vision problems but to project an image of being more educated and cultured.

All the bling aside, Aw Boon Haw and his brother were also generous philanthropists, donating significant portions of their company’s revenue to various causes, including schools, leprosaria, and disaster relief.

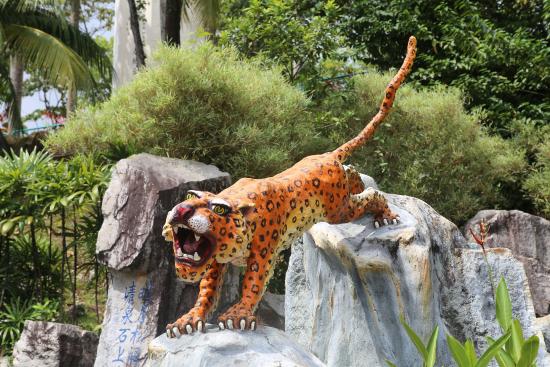

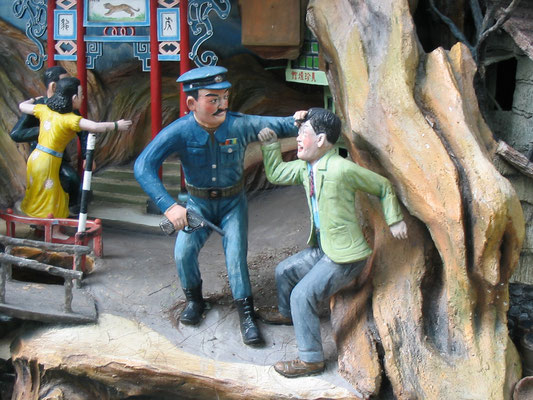

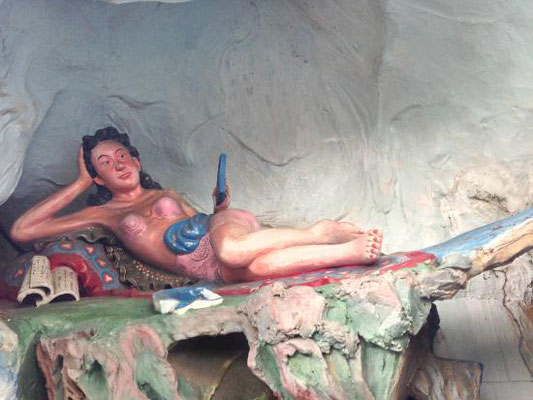

In a next stroke of genius, Boon Haw created the Tiger Balm Gardens theme parks (later known as Haw Par Villas) in Hong Kong (1935), Singapore (1937), and Fujian Province, China (1946), which served as somewhat bizarre cultural and promotional landmarks blending Chinese mythology with product advertising.

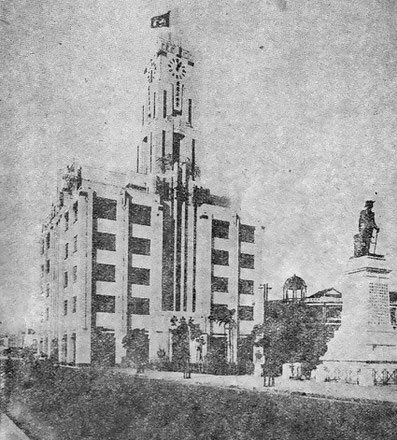

The pinnacle of Tiger Balm's presence in Mainland China however, was the construction of the Canton Eng Aun Tong factory in 1937.

Located on the Pearl River promenade in Guangzhou, this impressive building became the main production and distribution center for Tiger Balm products in China.

When completed, the Guangzhou "Hall of Everlasting Peace" was the second-tallest building in the city, surpassed only by the Art Deco Oi Kwan Hotel.

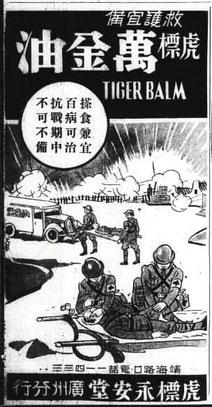

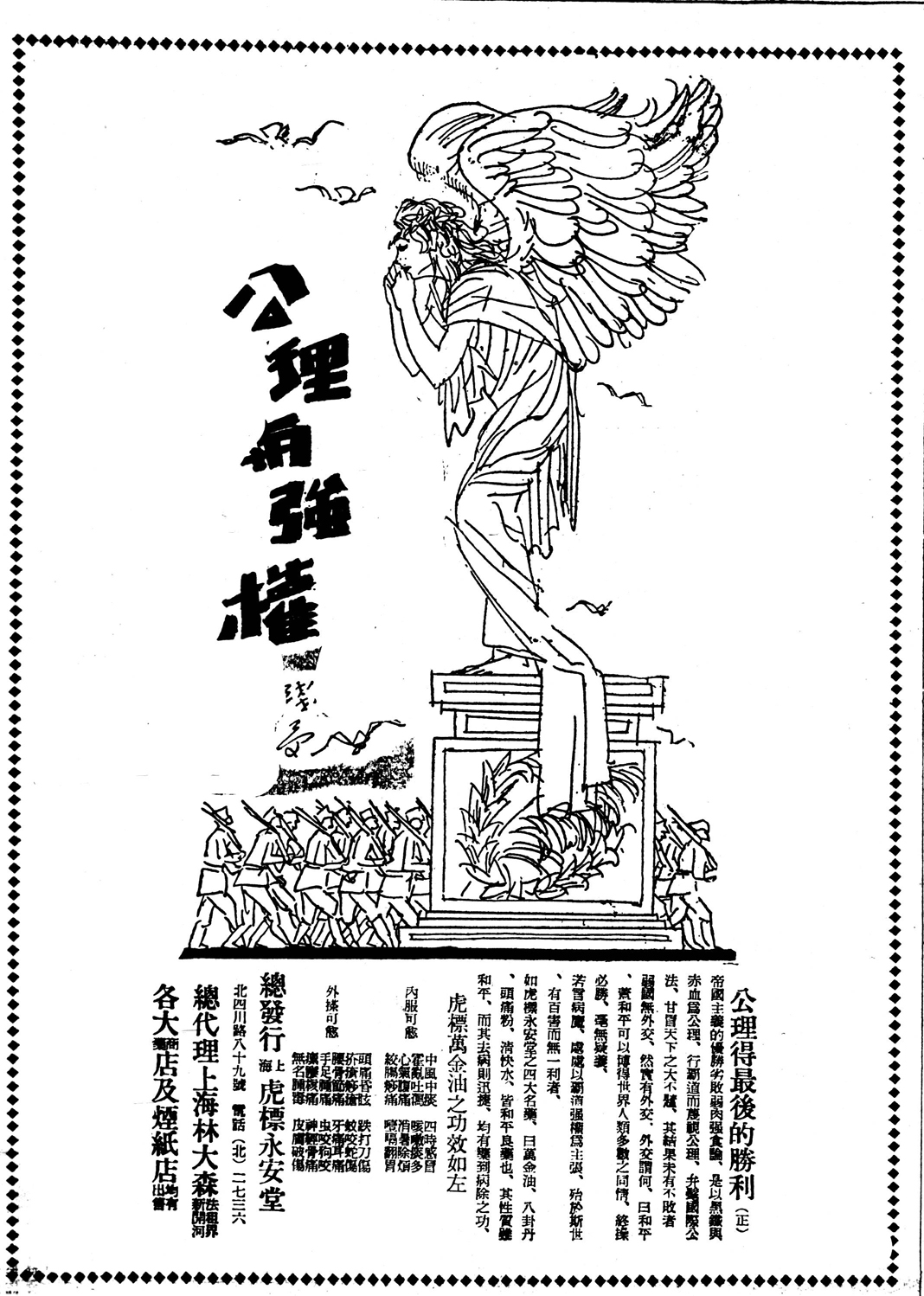

After the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese war later in the same year, a wave of boycotts against Japanese goods swept across the country.

Eng Aun Tong rallied its employees in China for anti-Japanese propaganda efforts and changed its advertisement in all of Asia.

The nationalistic branding of Tiger Balm initially led to massive success, finally beating its largest competitor, the Japanese pharmaceutical brand Jintan, which we wrote about here.

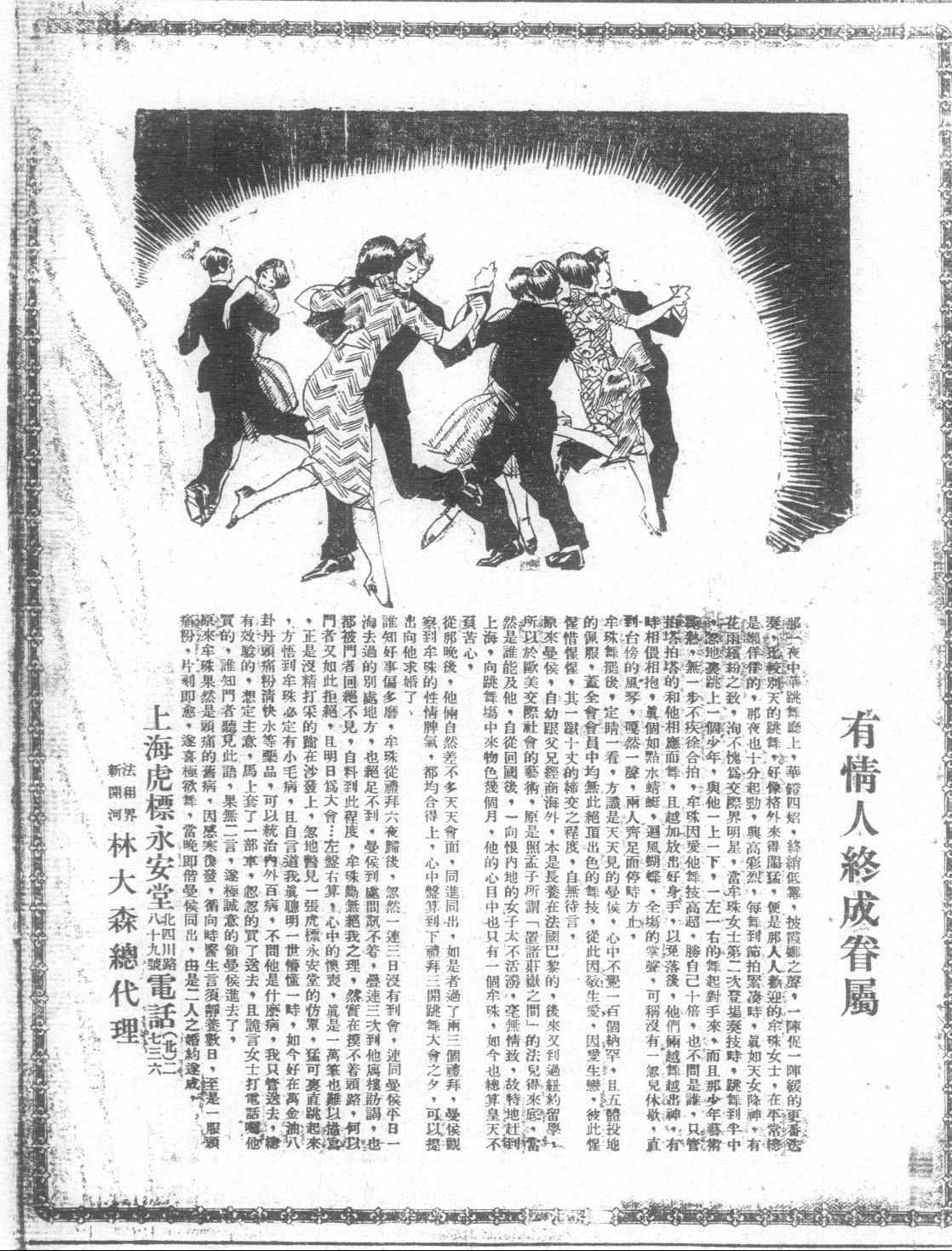

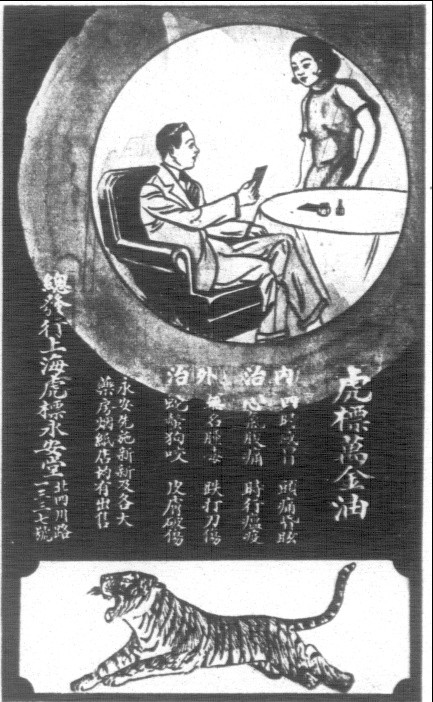

The advertisement flyer from our collection, stems from around that time. It was issued by the Eng Aun Tong Shanghai branch in the International Settlement (which was still outside of the control of the Japanese at that time) and features famous movie star Liang Caishan (梁賽珊). She and her sisters were heavily involved in propaganda efforts against the Japanese and eventually had to flee Shanghai to Singapore, where they went into hiding. A tragic story we wrote about here.

When the full-scale Pacific war broke out in late 1941, Eng Aun Tong was forced to cease its operations in China and most of Asia. Boon Haw fled to Hong Kong and managed the business from there, while his brother stayed in Singapore until he closed down the factory there and relocated back to Rangoon, where he died soon after in 1944.

After the war Eng Aun Tong recovered quickly and Boon Haw did everything in his power to restart and further expand operations, including lobbying with Chiang Kai-Shek in Taiwan.

The establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, however marked the beginning of the end for Tiger Balm's operations in mainland China. Initially, Aw Boon Haw attempted to continue the business but the industrialist was eventually labeled a traitor and the Guangzhou factory was classified as "enemy property" and confiscated, becoming the headquarters of the Guangdong Provincial Trade Union. From July 1950 onwards, Tiger Balm products and all publications from Aw's newspaper empire were banned from sales in the Mainland. For the first time since the 1870s, Tiger Balm completely disappeared from the Chinese market, marking the end of an era that had lasted over seven decades. Aw Boon Haw died in 1954 at age 70 following a major operation in Honolulu while on a trip to Hong Kong from Boston.

The story of the Aw family’s legacy in China took a remarkable turn in 1994 when the Guangdong Provincial Government decided to return the Guangzhou building to Aw Boon Haw's daughter, Hu Xian.

She initially considered using the building as offices for media investments in mainland China, but upon learning that private media remained strictly prohibited, she decided to donate the building to the Guangzhou municipal government for public welfare purposes.

While the original Eng Aun Tong facilities in China never returned to pharmaceutical production, Tiger Balm as a brand gradually re-entered the Chinese market during the Reform and Opening period of the 1980s and beyond. This return was managed by the Singapore-based Haw Par Corporation, which had acquired the Tiger Balm business from the Aw family in 1972 and has operated it since.

Write a comment