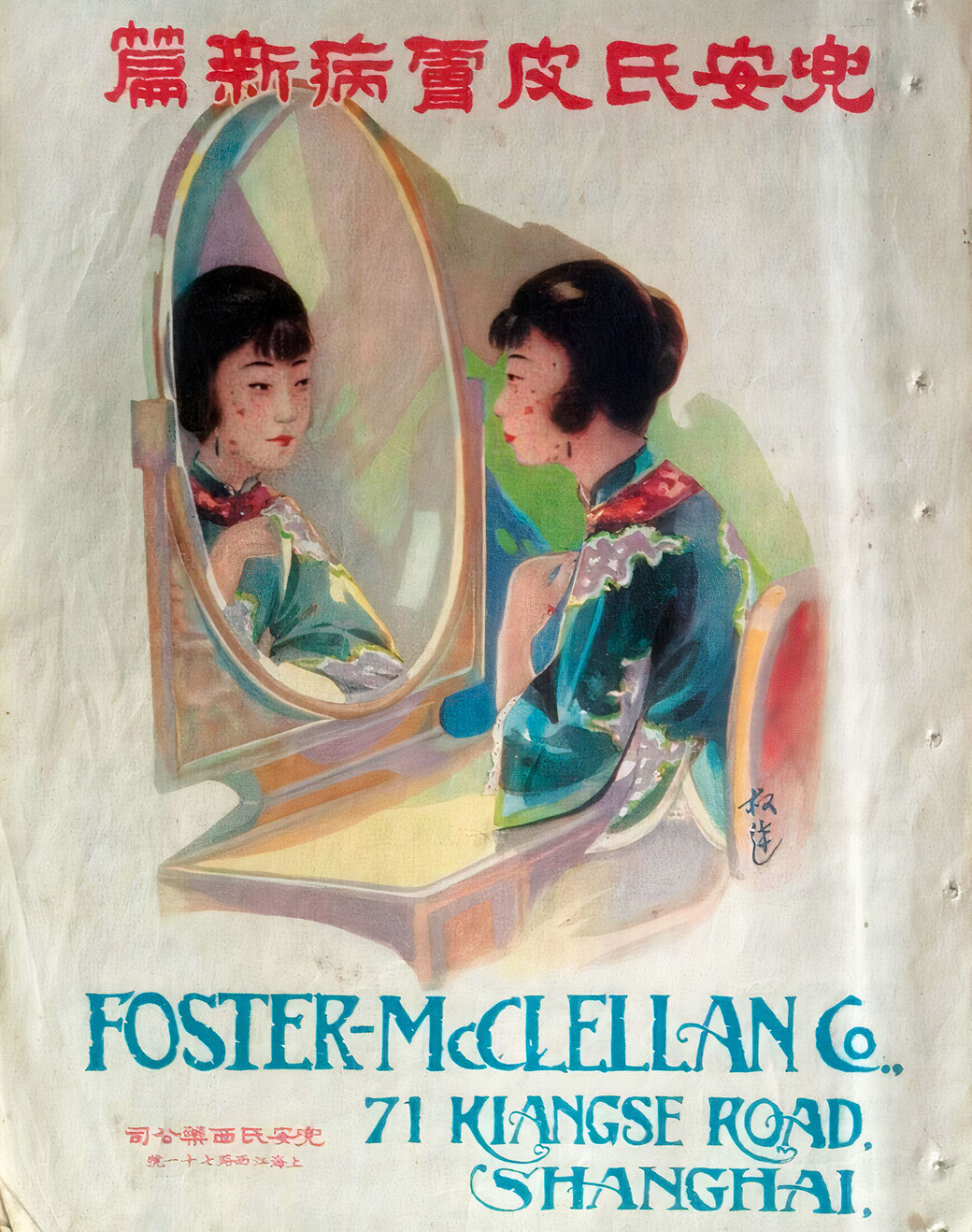

A lovely and innocent Chinese girl in 1920s fashion, advertising a skin medication by Foster-McClellan in Shanghai. A check in the historic “List of American firms at Shanghai” by the US consul identifies the company as “importers of patent medicines”. What dark secrets could this fair facade possibly mask?

Well, for starters, patent medicines are not, as the name would suggest, medicines that have been patented but rather they are commercial products secured by a trademark and containing ‘secret ingredients’ that were sold directly to the unsuspecting public to cure a variety of diseases, aches and pains. Most of these supposed panaceas in fact were dangerous remedies at inflated prices that would do more harm than good, even, in some instances, causing death to the patient. These types of quack remedies first emerged in the 17th century and peaked in the 19th century when patent medicines were one of the first major product categories that the advertising industry promoted. Patent medicine men pioneered many innovative advertising and sales techniques that were later used for other mass-market products. The term today is synonymously used with hucksters, charlatans or snake oil salesmen, evoking a mental image of travelling road shows with a bogus doctor in a top hat peddling his elixirs, tonics or liniments. During the emerging age of mass production by the turn of the 19th century however, a number of patent medicine men metamorphosed from rural peddlers into businessmen of considerable sophistication.

One of the prime examples of this evolution were Doan’s Kidney pills, invented by the Canadian pharmacologist James Doan (1846-1916) from Kingsville in Ontario, Canada.

He claimed to have been given the formula for the pills from the mysterious Quakeress “Aunty Rogers” as it is retold in an advert from 1900.

In 1894, Doan sold the rights to his medicine to Foster, Milburn & Co., a patent medicine manufacturer from Toronto and it would soon become their flagship product. The firm was started around 1860 and also had a branch for handling American sales established at Buffalo, New York in the 1870s.

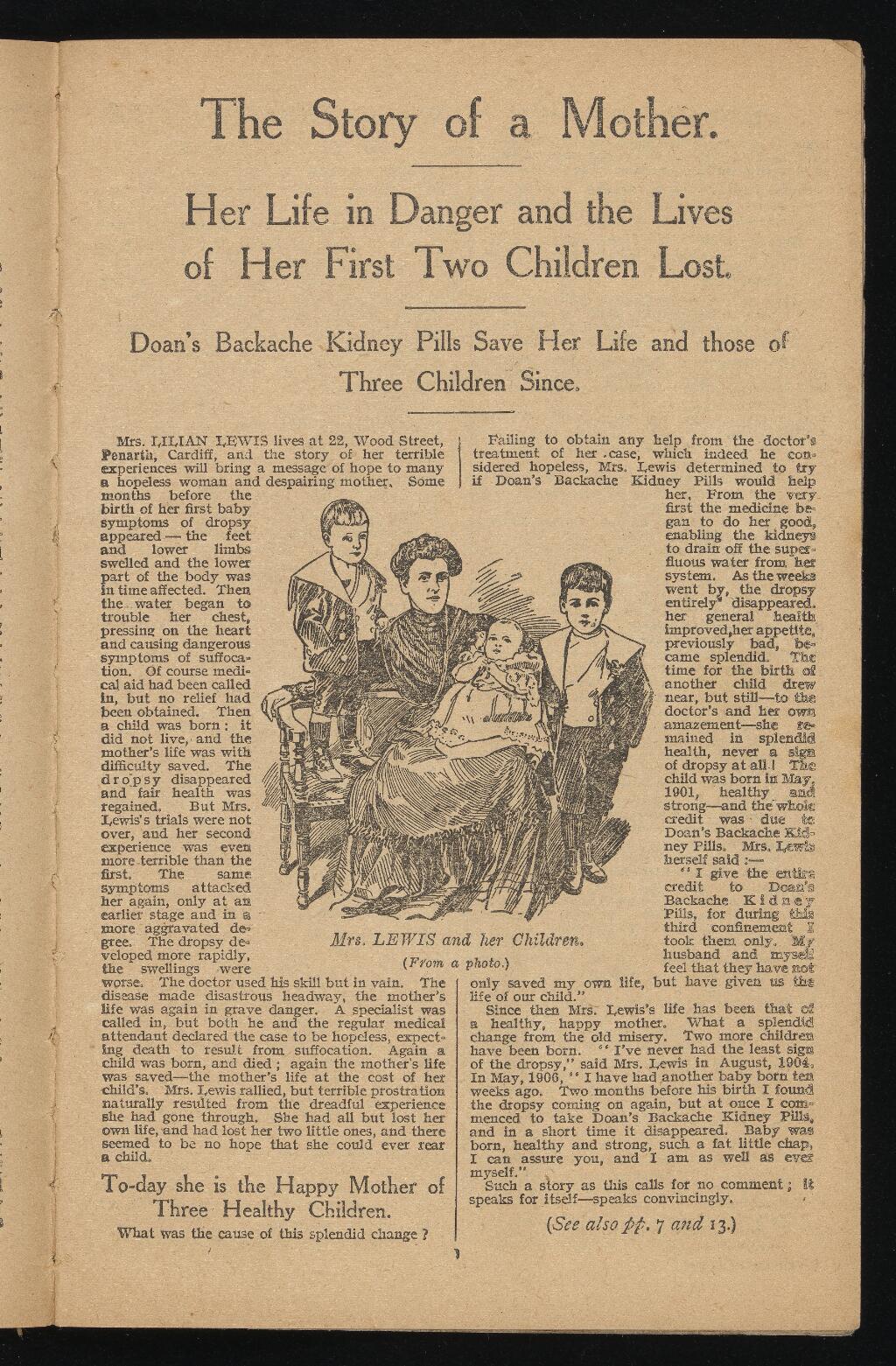

The primary means of marketing its dubious goods were adverts in the form of persuasive testimonials in country newspapers from local residents who had experienced some miracle recovery from an otherwise incurable ailment. The ads contained smart calls to action for free samples, which were followed up with direct marketing tactics such as sending guide books, directories and monthly customer magazines.

In 1898 Edwin McClellan started to work for the Foster Milburn Company of Buffalo. An ambitious young man, he soon went to London and opened a branch, Foster-McClellan Co., which prospered, selling its products throughout Europe. The group additionally established a sales office in Sydney, Australia.

In 1905 Collier’s magazine published an influential exposé of the patent medicine fraud, titled "Death's Laboratory". The growing public awareness of the fraudulent practices in patent medicine prompted the passing of The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt to ensure significant consumer protection.

It among others required that active ingredients be placed on the label of a drug's packaging and that drugs could not fall below purity levels established by the United States Pharmacopeia or the National Formulary. The act ultimately also led to the establishment of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Foster, Milburn & Co knew that their days in the Western world were numbered and set out for new shores: Led by McClellan from the London office in 1906, fabricated testimonials began appearing in English-language newspapers in China, with sensational headlines such as "GRATEFUL MOTHER: Tells how Doan's Backache Kidney Pills saved her Son's Life" and "OLD AND YOUNG ARE CURED OF DISEASE BY Doan's Backache Kidney Pills." All of these advertorials mentioned a London address where the miracle medicine could be purchased by mail-order and shipped internationally.

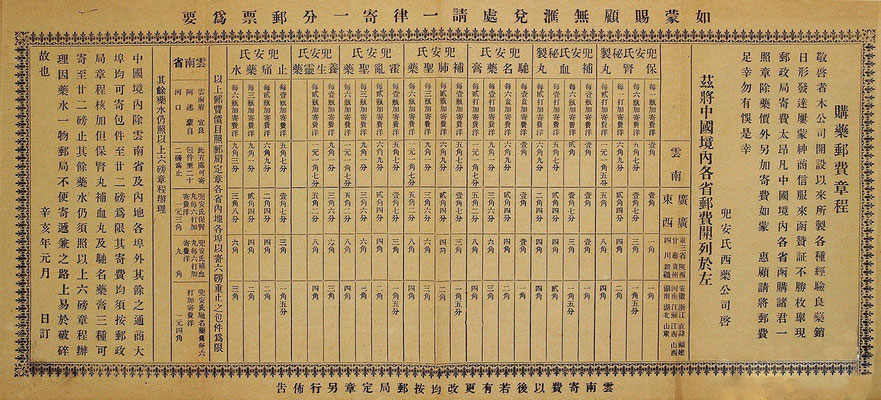

These initial tests with the foreign populations of the international settlements seemed to have been successful and in 1909 Foster-McClellan incorporated their own company (兜安氏西藥公司) in Shanghai on 9 Siking Road. From there on the adverts increased in volume and now mentioned the local address for mail-orders as well as the availability of products throughout dispensaries in China. In 1911 the company went all-in with adverts in Chinese language newspapers and magazines, calendar posters, billboard advertisements, activation events as well as direct mailings of coupons and their monthly customer magazine (from which the advertisement from our collection stems). The Doan’s mail order catalog for distance selling was particularly innovative and included a table of postal fees for delivery for across China.

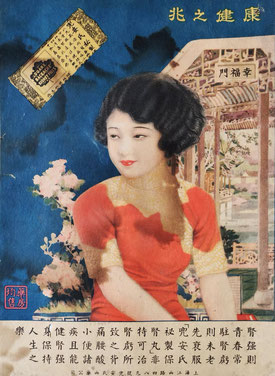

In the early 1920s Doan’s (兜安氏) had become one of the most active, if not the most active ‘pharmaceutical’ advertiser in all of China. Their adverts and promotion tactics were a master-class in persuasive consumer marketing filled with an exaggerated rhetoric of miracles and panacea (良藥 liangyao). They included carefully crafted keywords such as “secret formula” (秘製 mizhi), “heals rheumatism” (風濕 fengshi), “and bone and kidney ailments” (腎 shen), “strengthens the constitution (frame) and invigorates intelligence”, “alertness” (聰明 congming, 敏捷 minjie), “purifies the blood” (濾清血液 luqing xueye) and “gives a feeling of well-being and of inner comfort” (幸福 xingfu, 内 nei). On top of all of this Doan’s applied premium pricing to their near-worthless products and value-signaled to consumers with the catchy tagline “Good products are not cheap and cheap products are not good” (好貨不賤賤貨不好).

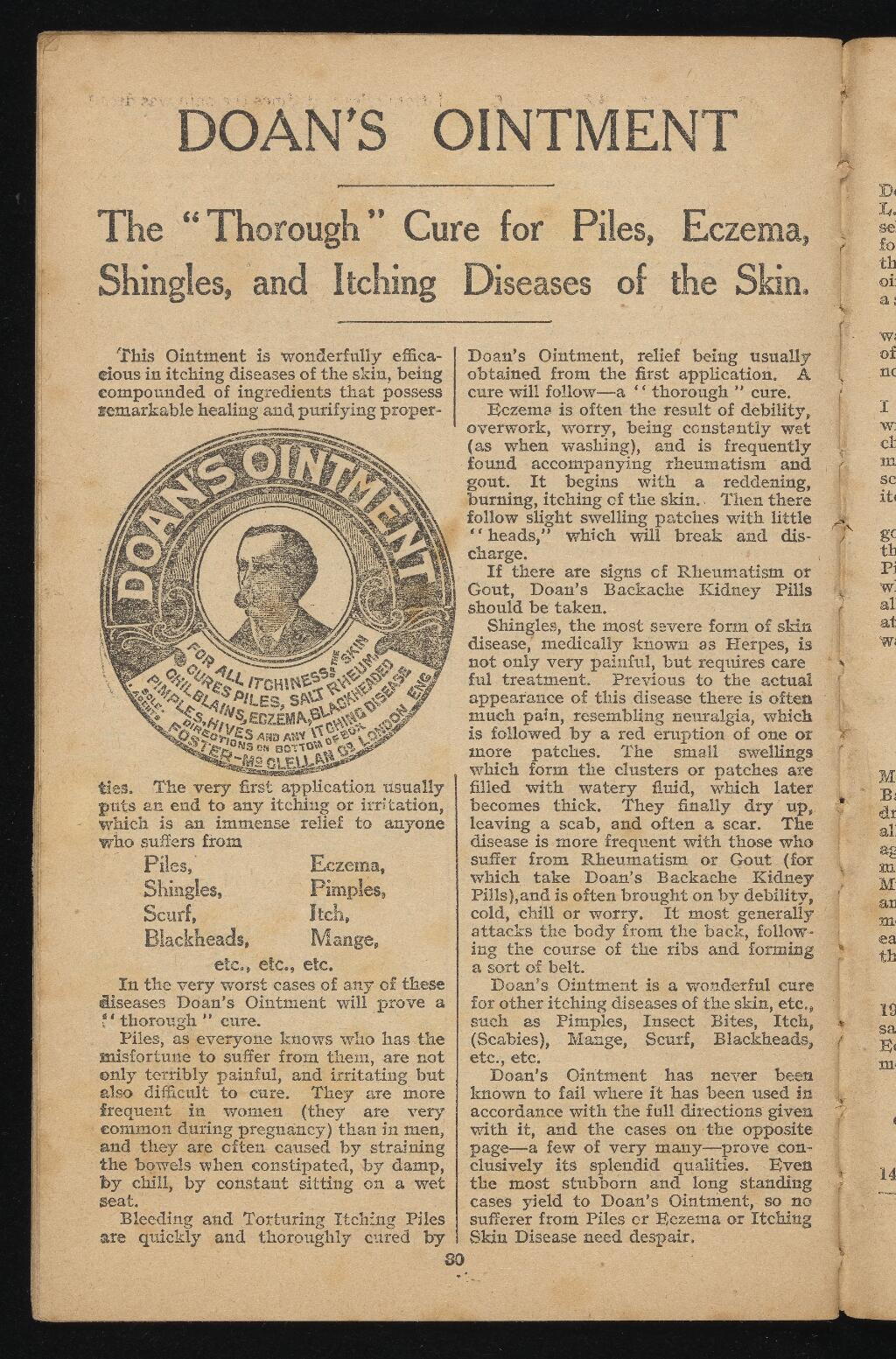

By 1921 modernity finally caught up with the old-timey patent medicine men Foster, Millburn & Co in the USA when Doan’s kidney pills were identified as “nostrum” – a potentially dangerous quack remedy, by the American Medical Association, and sales in the West started to decline. But in Republican China with its instable political administration, lagging legislation and the concept of extraterritoriality in the international settlements, nobody seemed to have noticed nor cared: the 1920s were in fact a golden period for Doan’s and their fellow patent medicine importers to China. The company was so successful, that it expanded its categories to “Doan’s Ointment” for treating skin disease (featured in our advertisement) as well as Doan’s Anti-Constipation Pills and Doan’s Lung Tonic.

It is unclear which advertising agency was responsible for creating and placing the numerous adverts for Doan's, but it is evident that their early entry into the market and the omnipresence of their ads made it challenging for new brands to gain a foothold. The famous ad man Carl Crow gives a hint in his seminal book “400 Million Customers”, that his agency was active in this category, while at the same time acknowledging the questionable nature of patent medicines by writing that “A large number of foreign manufacturers are selling their remedies here, some as 'ethical ' preparations which are prescribed by doctors, and others as household remedies which will make the employment of a doctor unnecessary”.

He goes on to say, “The pages of the Chinese newspapers are full of medical adverts. We handle the advertising for several of them. All have been selling here for a generation or more and have built up sound reputations and a profitable following. These remedies appear to satisfy the existing demand completely and so leave little room for the introduction of any new competing nostrums.

The present generation wants the pill that cured grandfather's backache and will take no other. That is all very fine for the brand which cured grandfather, but discouraging for the man who is trying to put a new pill on the market.”

Towards the end of the Roaring ‘20s, a gradual decrease in the frequency of ads for Doan's in Chinese newspapers can be observed.

This decline is likely due to a combination of factors such as the establishment of the first Ministry of Health under the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek in 1928, resulting in tighter regulations; increased competition by legitimate OTC brands with superior efficacy, the rise of barbiturates and the height of morphine abuse in the 1930s, primarily instigated by the Japanese to undermine the Chinese people.

The Second Sino-Japanese War eventually put Doan’s business in China to a complete halt and even though it briefly restarted during the period between the end of the Pacific War and the Communist Revolution, sales never recovered to their 1920s peaks. Sometimes after 1949 Foster & Milburn’s trademark rights were taken over by an even bigger fish in old-school patent medicine: G. T. Fulford & Company. Like Foster & Milburn, Fulford was a Canadian enterprise but its founder George Taylor Fulford made it all the way up to the Canadian Senate, giving him distinct influence. His company had also aggressively marketed their quack products in China, most notoriously “Dr. Williams' Pink Pills for Pale People”.

It would be reasonable to assume that none of these phony brands still exist in 2023, but one should never underestimate the power of advertising for it can truly transcend time and endure the ages: over a century after it was introduced to the Middle Kingdom, Doan’s Ointment is in fact still sold in China. It is manufactured and marketed by a subsidiary of Hutchinson Group, Medipharma Ltd. in Hong Kong “under license from G.T. Fulford Ltd”.

Even the infamous Doan's Backache Kidney Pills have proven to be indestructible. The brand rights first ended up with Novartis, one of the largest pharma businesses in the world. In 1996 the FTC charged the company for violating federal law with its unsubstantiated claim that “the product is superior in providing back pain relief”. In 1999 it was ordered to run corrective ads and modify the packaging. Several years after the brand had been taken off the market, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories acquired the trademark rights in 2017. To this day the multi-billion USD Indian pharma company continues to sell medication for back pain under the controversial, yet time-tested Doan’s brand name.

Write a comment