The crumb trail of Bakerite leads us back to the American James David Sullivan, who after serving in the Spanish American War, came to China at the turn of the century and established the Denniston & Sullivan photo supplies store on Broadway (today’s Daming Rd.) in the Shanghai International Settlement. In June 1906 Sullivan sold the business to former employees Messrs. L.L. Hopkins and J.J. Gilmore who continued to operate it but moved it to Nanking Rd. (todays Nanjing East Rd.)

J.D. Sullivan left China for the USA to get married in December 1906. After his return to Shanghai in 1908, he used the proceeds from the sale of his previous business to start a new large scale and state of the art photography studio next to the Astor House Hotel on Broadway, called Burr Photo Co.. The workshop was a busy place and to entertain its customers Sullivan and his wife Josephine in the same year opened Sullivan’s Candy Store right next door. Over the years this confectionery shop and bakery became immensely popular, not only among the foreign residents of Shanghai, but also the Chinese. Especially its cookies hit a nerve: to this day “So-li-ven” is used as a synonym for fruit biscuits in the local Shanghainese dialect.

The business of the candy store thrived and in around 1914 Sullivan’s moved across Suzhou Creek to No. 11 on Shanghai’s biggest shopping street, Nanking Rd., and eventually expanded to a full-fledged restaurant with adjacent bakery and confectionery store.

The new English name was Sullivan's Fine Candies and the previous formal Chinese business title Měi lì fēng (美利丰) was changed to Shālìwén (沙利文), reflecting how the locals had already referred to the store for close to a decade. Legend has it, that Sullivan’s self-baked bread, which was complimentary with lunch sets at his restaurant, single-handedly popularized the staple food, previously unknown to the Chinese. From 1917 onwards J.D. Sullivan no longer worked at Burr Photo Studio and instead focused on personally managing the booming candy store. Already in 1920 Sullivan’s grew further and moved to an even bigger location on No. 36 Nanking Road, eventually with a total of 230 seats for the restaurant.

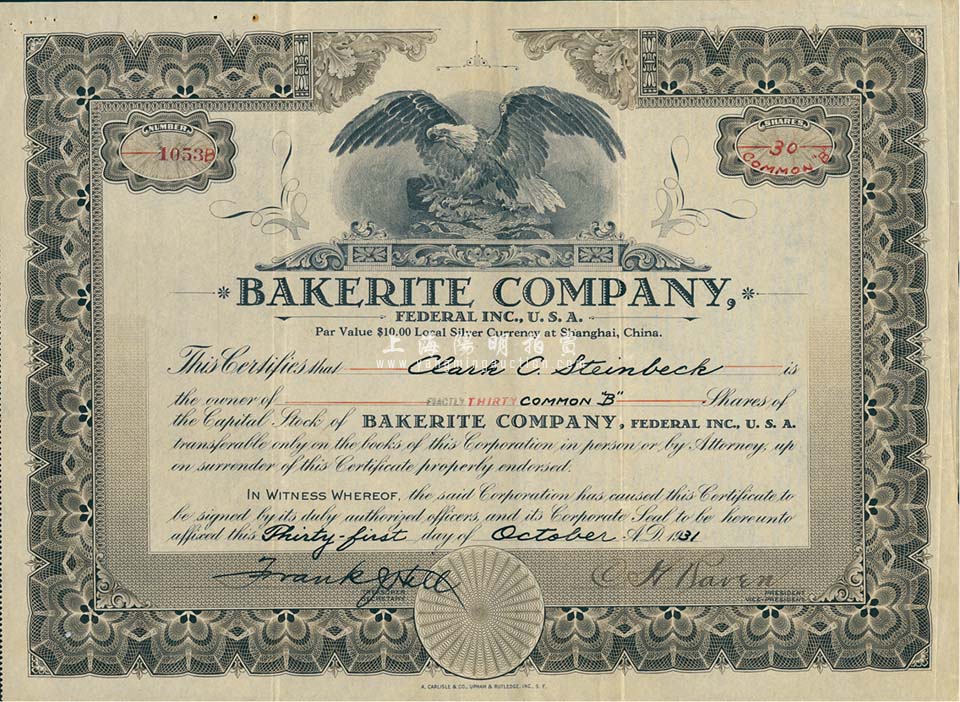

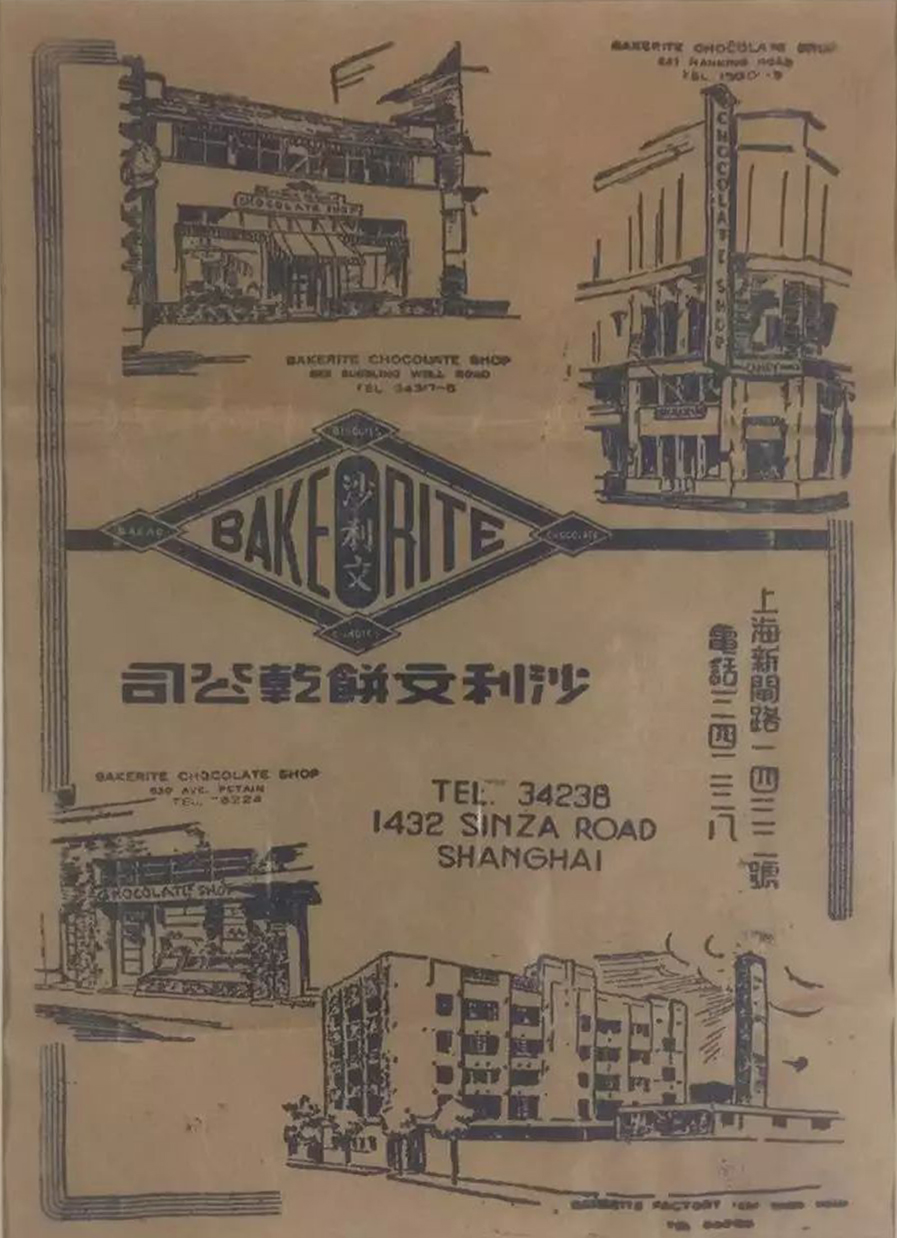

By 1921 institutional investors got wind of the booming Shanghai pastry and bakery market and Bakerite Co. Federal Inc. USA was formed. The company bought an old textile mill that had gone out of business and turned it into a factory to manufacture food, candies, cookies, ice cream, and “all the good stuff”. In the same year Bakerite acquired Sullivan’s Fine Candies, renamed the restaurant to the iconic “The Chocolate Shop” and the attached bakeshop to the “Bake-Rite Bakery”. But the tasty tale of this over a century old Chinese brand did not end here: Even though James D. Sullivan exited the business and went on to invest his money in the import and trade of motorcars, the new owners kept the by now already legendary Chinese name Shaliwen for both the company (沙利文面包饼干糖果公司) and the restaurant.

The new manager of the Chocolate Shop and president of Bakerite was the American Charles “C.H.” Raven, but its key shareholder was the Raven Trust Company – the holding company of Charles brother, the notorious Shanghai finance and real estate mogul Frank J. Raven.

Raven was a Californian-born engineer and, just like Sullivan, a Spanish American War veteran. He arrived in China in 1904 to re-invent himself from a tea-totaling church goer to a self-made founder of a financial powerhouse based in Shanghai with an empire spanning banking, real estate, commodities, and insurance. Raven’s economic clout can even be credited with the spawning of today’s American Insurance Group, better known as A.I.G., with his friendship and financial support to that company’s credited founder Cornelius Vander Starr in Shanghai in 1919.

Just like with his other Shanghai endeavors Raven continued to bake up success with Bakerite and in 1925 a second location called “The Little Chocolate Shop” was opened on 565 Avenue Joffre (todays Huaihai Middle Rd.) in the French Concession. F.J. Raven also cleverly installed strategic advisors and shareholders in the business: Allegedly the renowned American “Shanghai Lawyer” Norwood Allman as well as H.P. Henningsen, the owner of the Henningsen Produce Co. (manufacturers of the famous Hazelwood ice cream), became silent directors or equity holders in the Bakerite company.

What is definitely confirmed, is that in 1926 the young advertising professional C.P. Ling was appointed as a director to the company and Bakerite became the first client for his newly formed China Commercial Advertising Agency (C.C.A.A.).

A report by the US Commercial Attaché, several years later noted that “The Bakerite Company spends a great deal of money on advertising in both the English-language and Chinese-language newspapers as well as over the radio. The advertisements, displays, pamphlets etc. are especially noticeable at this time of the year (December), when the company is looking forward to the very profitable holiday season.”

The support of C.P. Lings patron F.J. Raven, undoubtedly was a key driver that catapulted C.C.A.A. to become the largest of the “big 4” Shanghai ad agencies by the 1930s, second only to Millington Inc. and ahead of Carl Crow Inc. and Consolidated National Advertising Co.

In 1926 also the trademark “Bake-Rite” was formally registered, laying the foundation for the wholesale trade of packaged consumer goods such as cookies, biscuits, candies as well as old Sullivan’s famous bread.

In the same year the business re-started distance selling via mail order across China or abroad, "sent to steamers or mailed to Outports". A sales channel Sullivan's had already pioneered and advertised in the mid-1910s.

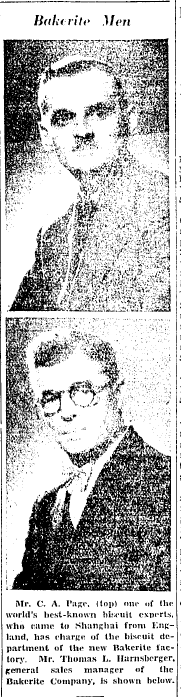

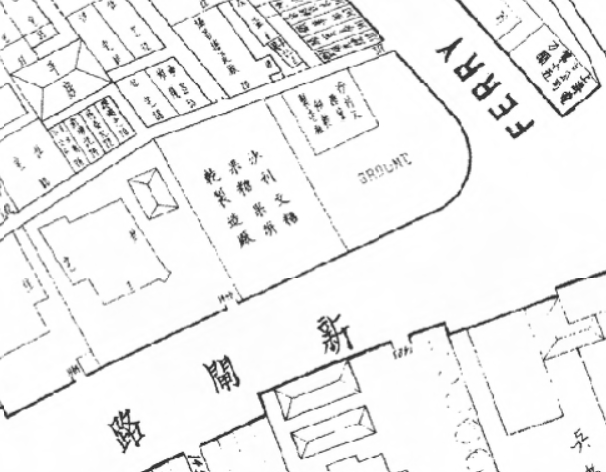

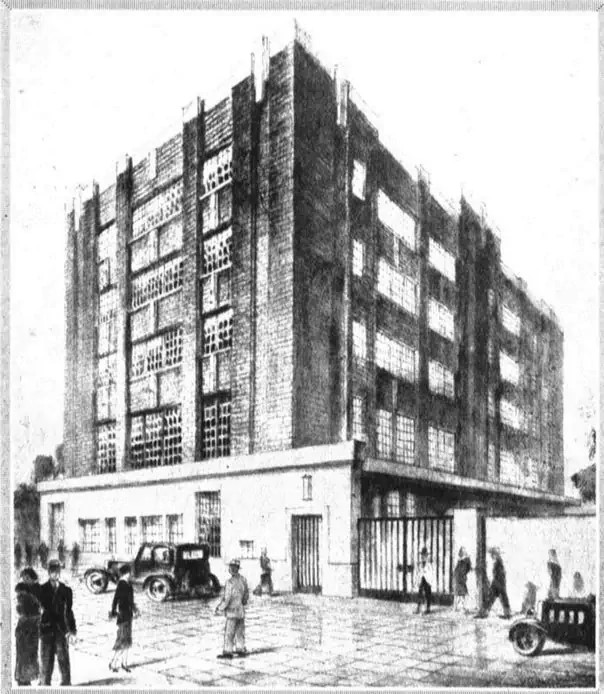

In 1931 Bakerite issued public shares and used the capital to construct a modern new 5 storey factory in the Western district of the International Settlement. It was opened in January 1933 on the corner of Sinza and Ferry Road (todays Xinzha and Xikang Road). The China-Press referred to it as “China’s first scientific bakery” with a capacity of “6,000 lbs. of biscuits per day, 30,000 lbs. of bread and baking products, 4,000 lbs. of candy and 1,000 lbs. of chocolate”. All the heavy machinery for the factory came from England or Germany with the main supplying company being the British firm Baker-Perkins.

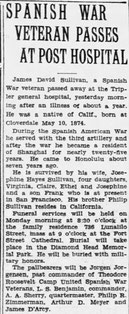

Sadly, the former "Candy King" of Shanghai, James David Sullivan, did not live to see the new Bakerite factory start production. He passed away on April 9th 1932 at only age 58 in Honolulu, where he had resided since 1925.

No news of his death was published in the Shanghai press and it seems the foreign population and business community had already long moved on and forgotten about the photography, bakery and restaurant pioneer. Only thanks to the loyal Chinese consumers who turned his name into a category-defining and generic trademark for biscuits, was his legacy preserved.

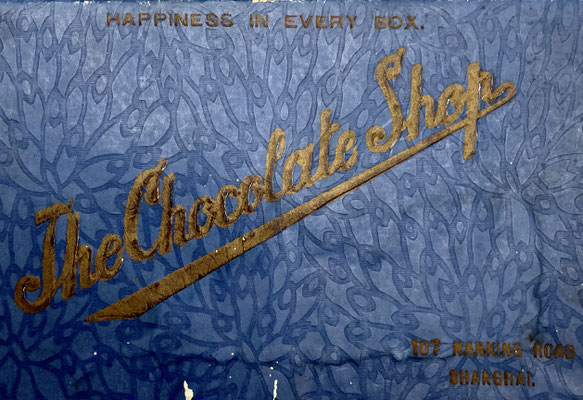

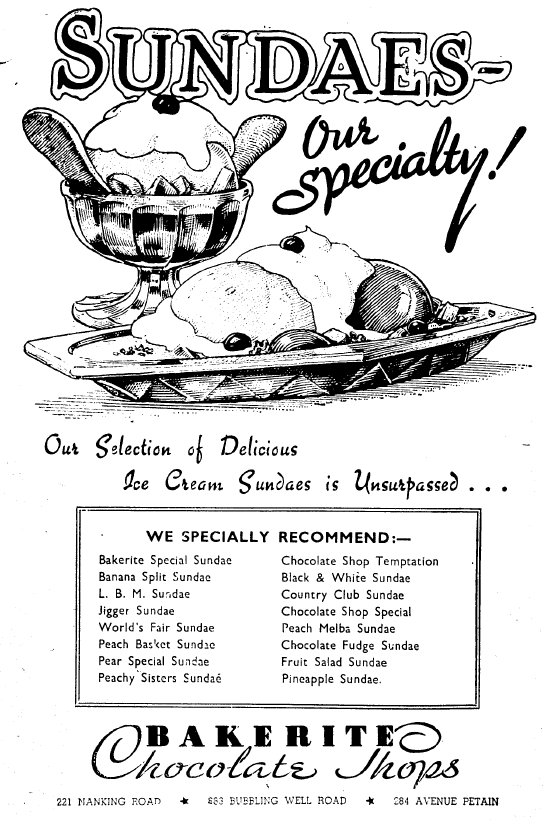

In 1933, the Chocolate Shop expanded to a third location on 883 Bubbling Well Road (todays Nanjing West Rd.) with its new "Western Branch" restaurant that had a capacity of an additional 100 seats. By that time its original “Eastern Branch” on No. 36 Nanking Road (later renumbered to 107, then 221), had become the go-to restaurant and confectionery for Anglo-Americans in Shanghai and was immortalized in countless memoirs of old China. J. G. Ballard for example — the British author of the novel “Empire of the Sun” based on his Shanghai childhood — fondly recalled “Saturday ice cream sundaes at the Chocolate Shop”.

But not only children were attracted to its sweet temptations, the Chocolate Shop also became the meeting point for an illustrious group of young American professionals, journalists and authors. Over salads and milk shakes, radicals like Harold Isaacs, Agnes Smedley and Edgar Snow (he met his wife in the Chocolate Shop) debated China’s future. J.B. Powell, the crusading editor of the China Weekly Review, “Judge” Allman, who presided over the Mixed Courts and American businessmen like advertising pioneer Carl Crow, joined with American missionaries, chorus girls and the odd conman to enjoy the best ice-cream sodas in the city. In 1935 the infamous writer Emily Hahn caused a sensation when she walked into the Chocolate Shop with her pet gibbon Mr. Mills draped across her shoulders.

An original box from the The Chocolate Shop in Shanghai. From the MOFBA collection.

It was all a great success story of an American businessman abroad, who at one point even was the president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China. But in 1935 F.J. Raven’s empire came crumbling down like a dry old cookie, in what Time Magazine reported as, “the most severe blow to American business prestige in China since the founding of the Shanghai International Settlement in 1843”. In short, Raven’s four flagship Shanghai firms – the American-Oriental Banking Corporation, the American-Oriental Finance Corporation, the Raven Trust Company, and the Asia Realty Company – closed their doors unexpectedly in late May 1935 to cries of economic ruin and, later, accusations of fraud and embezzlement. The result of the closure tarnished a name that took decades in Shanghai to build, bankrupted thousands of foreigners and Chinese alike, and ultimately landed Raven, a longtime American imperial elite, in a United States prison.

When the liquidations of his flagship companies were complete in 1937 only the Asia Realty Company and Bakerite were spared closure and got restructured. As the new manager of Bakerite, Mr. J.L. Holbrook, was installed. At that time the business employed approx. 500 staff and sold its products in its self-operated shops and restaurants as well as through wholesale distribution agreements across the Lower Yangtsze Valley to cities such as Nanjing, Suzhou and Hangzhou. Bakerite products were stocked by practically all Shanghai restaurants, bars, grocery stores and provision sections of department stores.

They also became increasingly popular with the Chinese population who were “gradually developing a liking for certain Western style food”. A trend that the new management immediately capitalized on and which resulted in tremendous growth for the company during the late 1930s: In 1935 Bakerite generated approx. 827,000 Yuan, in 1937 1,250,000 Yuan and by 1938 it reached 3 million Yuan in annual revenues. Besides the three Chocolate Shop restaurants Bakerite also catered for the U.S. Marines Club and two local cabarets. A considerable amount of private catering was also handled.

In the late 1930s a third Chocolate Shop branch was briefly opened on No. 530 Avenue Pétain (today's Hengshan Rd.) in the French Concession. It soon was moved to No. 284 and in 1939 the “Grimmy Apartments” building was erected next door on No. 288. The Chocolate Shop downstairs of the art deco apartment block became so popular that in the 1940s it was renamed to "Sullivan Apartments" (沙利文公寓) - a name the building still holds to this day.

At its peak, and despite the disgraceful conduct of its prior owner, Bakerite had become the most influential and powerful food production company in Shanghai. It's offering spanned across the categories of confectionery, chocolates, candies, cookies, biscuits and bread with illustrious English consumer brand names such as "E-Z Bite", "Jersey Milk", "Aristocrat", "4th Ave" and "Bake-Rite". Meanwhile the Chinese consumers mostly just continued to call them "Shaliwen".

After the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, alas, the Bakerite factory and the Chocolate Shop restaurants were taken over by the Japanese army. In 1946 business under American ownership briefly resumed but in 1949 the Western branch of the Chocolate Shop was closed and the Eastern branch was taken over by its Chinese employees.

In 1952 also the Eastern branch was closed and in 1954 the former Bakerite factory was merged into the Shanghai Yimin Food No. 4 Factory (上海益民食品四厂), which today has become part of “Guangming” Bright Food Group (光明食品集团), the second largest food producer in all of China.

Even though this marked the end of Bakerite and the Chocolate Shop, its Chinese name, and with that the name of its original creator, J.D. Sullivan, persists to this day and has become a beloved part of Shanghai's culinary heritage: The old “Shaliwen” trademark until today is owned by a Guangming daughter company, you can still take a bite into the past and taste the nostalgia thanks to the Shanghai Shaliwen Food Co. Ltd., which continues to produce the eponymous biscuits, and hidden deep inside the remains of the old Bakerite factory on No. 1432 Xinzha Rd. even a small “Shaliwen” store stubbornly defies time.

Thanks to https://avezink.livejournal.com/ for additional pictures of the Bakerite factory

Write a comment

Alice Raven (Wednesday, 01 January 2025 11:59)

Thank you so much for much more information than I previously had about The Chocolate Shop! C.H. Raven was my great-grandfather.. If anyone would like to exchange information, I can be reached at raviac@yahoo.com.