The Astor House Hotel was once the oldest and most reputable establishment in Shanghai, but in 1910 an unthinkable crime occurred at one of the most famous hotels of the world, that almost tarnished its reputation forever. Items acquired by us in the USA help solve the century-old mystery...

On 29 August 1842 the Treaty of Nanjing named Shanghai as one of five open treaty ports in China, and soon after in 1843 the British concession was established. Among the very first foreign residents was a Scottish merchant, Peter Felix Richards, who had been doing business in China since about 1840.

In 1846, Richards opened one of the first Western restaurants in Shanghai and the first Western hotel in China on the river front on the southern Bund, at Yang-King-Pang Creek, which in 1849 became the demarcation to the French Concession. The establishment was named Richards' Hotel and Restaurant after its founder, or “Lee-zo” in Chinese (礼查饭店). It initially targeted the seafaring clientele that made up the bulk of travelers to 19th century Shanghai.

While on an extended trip abroad, alas, Richard’s company was eventually declared insolvent 10 years later, on 15 May 1856, and all of his assets were assigned provisionally to its creditors, Britons William Herbert Vacher and Charles Wills. Wills is best remembered for building the first wooden draw bridge crossing Suzhou creek in 1856, linking the British Settlement in the south and the unofficial American Settlement in the north. After its completion it was henceforth referred to as Wills’ Bridge.

In February 1858 Wills relocated Richards Hotel to property he owned on the northern banks of Suzhou Creek, right across the new bridge. By 1859 the hotel was renamed in English to the Astor House Hotel, but its original Chinese name “Lee-zo” was retained and in fact lasted until 1959. The establishment continued to be managed by Richards but in 1861 it was sold to Englishman Henry W. Smith, which marked the beginning of numerous ownership changes, renovations and expansions over the decades to come.

In 1867 the Astor House Hotel was the earliest in Shanghai to use coal gas to provide lighting. On 15 November 1875 the Shanghai Municipal Council decided to re-name the part of Hongkew Road north and east from Whangpoo Road, “Astor Road” in reference to the by now famous establishment. In 1876 the hotel was enlarged, with fifty new rooms added and in 1879 former US President Ulysses S. Grant stayed there in Room 410. On 26 July 1882, the first electric street lamps introduced to Shanghai were installed in the Astor House Hotel, making it the first building in China to be lit by electricity.

Soon after, in 1883 Shanghai became the first city in China to provide piped water to its residents and once again, the Astor House Hotel was the first building in Shanghai to have the privilege of running water.

By 1890, “for foreigners the Astor House was the center of social activity” and in July 1901, the then owner Auguste Vernon floated privately the Astor House Hotel Co. Ltd. with a capital of $450,000. At that time the Astor was considered the primary first-class hotel in Shanghai and “the best hotel in all the Orient”. Also in 1901, the first telephones were installed in Shanghai, with the Astor House receiving the first call ever in the city.

The Hotel was called the “by far best hotel in the whole of the East, including Japan” in 1904. By 1907 the old wooden bridge across Suzhou Creek was replaced with the current Garden Bridge made of steel, which triggered the Astor holding company to embark on a completely new hotel, “fitting of Shanghai's growth and importance” and 'better than any in the Far East”. Even before the renovations the hotel already employed 254 persons and offered 120 rooms, each with separate bathrooms attached.

As part of the ambitious expansion plans a new hotel manager was recruited from Europe in January 1907, the Swiss citizen Mr. Walter Brauen, an experienced hotelier and “skilled linguist”.

Brauen was born 1 October 1876 in Interlaken and managed several prestigious hotels in Europe before relocating to Shanghai. The socialite, known for his billiard playing skills, soon blended in with the tightly-knit Shanghai foreign community and became among others a member and “Inner Guard” of the Kights of Phytias fraternal order and an office bearer in the local Freemasons.

The opening of a tram line in March 1908 over the new Garden Bridge and past the Astor Hotel greatly increased both access and business. Construction of the new building finally commenced in November 1908. It was scheduled to be finished by July 1909, however delays postponed completion until November 1910.

On 30 August 1910 the Astor Hotel company’s annual meeting was held, and despite the fact that chairman L.J. Cubitt publicly declared that he did “not think there is anything else in the accounts which does not explain itself” and “begged to propose that the report and accounts as printed be passed”, some grave inconsistencies must have surfaced during or shortly after this fateful assembly.

To everyone’s shock, ten days after the annual meeting, and only three months before the planned re-opening of the hotel, on 9 September 1910 an arrest warrant by the Mixed Court was issued for none other than the acclaimed Astor manager Mr. Walter Brauen. It turned out that a staggering total of $957 meant for staff salaries had been embezzled by Brauen in October 1909. At that time, Shanghai used the Mexican silver dollar as denomination and, based on the exchange rates in September 1910, the stolen sum when converted and adjusted for inflation amounted to approx. USD 21,000 in today’s value. Salaries and costs of living in Shanghai, however were considerably lower, with a Chinese coolie for example only earning around 6 Mex. Dollar per month and a pound of beef costing between 12 to 19 Mex. Dollar Cents. The stolen sum was therefore considerable and the theft marked an unprecedented scandal in the honorable hotel’s history.

The police immediately made a search for Brauen, but he could not be found and there seemed to be little doubt that he decided to leave Shanghai when he became aware that inquiries were being instituted at the Astor House. Indeed, on 19 September 1910, The North-China Daily Herald reported that Brauen had been spotted in Nagasaki, but the elusive manager once more evaded capture, disappearing into the shadows of the foreign port. It was the last time, Walter Brauen was ever seen or heard of in Shanghai again.

That is, until we acquired the advertising luggage label now in our collection, which was part of a larger stack of documents from exactly the period of Brauen’s mysterious disappearance. The pieces originated in the USA, are in pristine condition. The letter head of the hotels stationary, which was part of the find, explicitly mentions Brauen as manager. How did these materials end up in the USA and could they have been brought there by Brauen himself as painful reminders or even trophies of his crimes? Did Brauen not escape from Japan to his home country of Switzerland but instead ended up in America?

The answer might lie with Brauen’s wife, Roberta Cheyenne Fical, who was born 1880 in Colorado, USA. And indeed, US census records, surfaced as part of our investigation, reveal that Brauen entered the US in early 1911, just around the time of the official re-opening of the new Astor House Hotel back in Shanghai on 16 January 1911.

Already prior to that, in October 1910, Scotsman William Logan Gerrard was appointed as new manager. The Astor House Hotel, facing financial setbacks and a tarnished reputation, pressed forward with its opening plans and did everything to sweep the brewing scandal of Brauen’s shameful crimes under the rug. No word of the incident was ever mentioned again, let alone leaked to the news press outside of Shanghai. Instead, the company focused all communication on the re-opening, advertising the new 211-room hotel as “the Waldorf Astoria of the Orient” and in another advertisement described it as the “Largest, Best and Most Modern Hotel in the Far East”. The new Hotel now had a 24-hour hot water supply, some of the earliest elevators in China, and each of the guest rooms had its own telephone.

A major feature of the reconstruction was the creation of the Peacock Hall, “the city's first ballroom”, which became renowned for its dinner-parties, and balls. A highly convincing proposition for party-hungry Shanghailanders, and by the time the hotel was re-opened in January the Brauen incident it seems was long forgotten by the foreign community. To the Astor’s luck the news also never spilled beyond the borders of the Shanghai International Settlement.

But what became of the cunning Walter Brauen? Surely, he must have changed his name and transitioned to a new line of work to conceal his criminal past. Surprisingly (or not?), it turns out that what happened in Shanghai, stayed in Shanghai, to not only the Astors but also Brauen’s benefit. Already in 1912 Polk’s Medical Register lists Brauen as manager of the Byron Hot Springs Resort in California. The elegant and prestigious resort and spa was located in rural eastern Contra Costa County.

The next trace of the rogue Swiss manager can be found in an article from 6 January 1917 in “The Hotel World” magazine, which notes that Brauen was appointed director of the respected Yavapai Club in Prescott Arizona, “one of the finest buildings in Arizona that was as completely equipped as the finest gentleman's club in San Francisco or New York". The article does not miss to mention that Walter Brauen formerly worked for the world-famous Astor House Hotel in Shanghai and the Byron Hotel in California.

But Brauen’s incredible career in the hospitality industry far from ended there: after one year of “satisfactory service”, he left the Yavapai and joined as superintendent of service for the Du Pont Powder Company near Richmond, Virginia. This factory was built for the war effort and Brauen had “a complement of 80,000 employees to superintend”, as a newspaper article reports. It further mentions that, “He had jurisdiction over the personnel, welfare, insurance, efficiency and housing of the entire plant at Seven Pines Bag Loading Station, about 3 miles from Richmond.”

The same news article from 17 May 1919 furthermore states that in February 1919 Brauen, “The Hotel Man That Served In War” had to leave his position, because the plant closed after the end of WWI. Brauen is reported to have been offered a job in France but decided to stay in the USA where he pursued further opportunities with Du Pont in Washington and New York for Gotham Hotels. Little did his employers know that there might have been very good reasons for Brauen not to return to Europe, since the Shanghai Mixed Court would have surely informed the Swiss authorities to extend the search for him there.

We do not know where Brauen worked during the next decade, but the 1921 California Automobile Registration listed him as an owner of a Buick Coupe in the Golden State. One year later, the press reports of what must have been a very close call for Brauen while attending a “merry gathering of mystics”, hosted by the Los Angeles Society of Magicians at the Masonic Temple. One attendee, Charles J. Carter, reportedly recognized his “old acquaintance Walter Brauen”, who had “looked after the comfort of the magicians, when in Shanghai, China”. Bound by the unyielding bonds of the Masonic Oath, Carter, as his fellow brother, chose of course silence over divulging Brauen’s dark China secrets.

Meanwhile back in Shanghai, the Astor was thriving and in 1920 the Shanghai Stock Exchange opened at its premises where it remained until 1949. In the same year renowned British mathematician Bertrand Russell lodged at the Astor and in 1922 the establishment even hosted Albert Einstein, who stayed in Room 304.

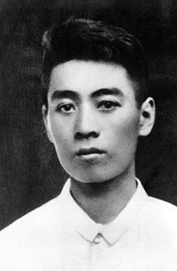

The hotel was renovated once more in 1923 by the Spanish architect Abelardo Lafuente to "keep up with the Shanghai passion for nightly entertainment." The ground floor was remodeled, with a new ballroom and dining room and its new grill-room soon earned distinction. The Astor House orchestra by then was under the direction of the celebrated "Whitey" Smith and later the orchestra of Ben Williams, the first American orchestra to travel to Shanghai, also played at the Astor House ringing in Shanghai’s famous Jazz Age. In 1927, future Premier of the People's Republic of China, Zhou Enlai stayed in the hotel for two months, as reported by Paul French, posing as a tourist during the 1927 massacre of Communists when there was a price on his head.

By 1930 the Astor was no longer the pre-eminent hotel in Shanghai. The completion of the Cathay Hotel in 1929, "threw a painful shadow upon the old-fashioned Astor House” and the center of social activity shifted from the Astor House around the corner to the air-conditioned ballrooms of the Cathay. By 1932 the location of the Astor had deteriorated, due in part to the proliferation of Japanese businesses and residents, with many Chinese refusing to cross into the Hongkou district. But even then, the famous old name still attracted celebrities such as Charlie Chaplin who allegedly stayed at the Astor in Room 404 in 1931, although some reports claim he only docked in Shanghai on his way to America but never left the ship. For his second visit in 1936 Chaplin is confirmed to have stayed at the Cathay instead.

During World War II and the Japanese occupation, “the Astor House fell into decline, and its elegance was soon no more than an almost unimaginable memory.” Likewise, also Walter Brauen's once glamourous career in some of the best hotels of the world seemed to have taken a turn for the worse during that time. An advertorial in the Southside Virginia News from 7 September 1939 peddles his firm in Richmond “paying best prices for butcher cows, heifers, calves and hogs”.

On 1 October 1949 the People's Republic of China was proclaimed, forcing Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek to flee. According to some accounts, Chiang had his last dinner on the Chinese mainland at the Astor House, before flying into exile.

On 19 April 1954 the Hotel was confiscated by the government and on 27 May 1959, the name was changed to the Pujiang Hotel (浦江饭店).

Ironically, Walter Brauen, the man who almost destroyed the reputation of what was described as once "one of the famous hotels of the world", "the pride of Shanghai", "a landmark of modern Shanghai" and perhaps hyperbolically "once the most luxurious hotel in the world", outlived the renowned Astor name by 5 years and passed away on 11 December 1964 in Los Angeles at 88 years of age.

In December 2018 the Pujiang Hotel was converted to the China Securities Museum, and the renovated premises are now once again accessible to the public. Photos below by the MOFBA from an earlier visit in 2017.

Write a comment

Christian Brutzer (Sunday, 26 November 2023 20:44)

Great story!