This 1930s postcard from our collection reminds us of the lost profession of billboard painter, signwriter or “wall dogs” as its practitioners were often colloquially called. Commercial advertising has a long history in China and in the West but as an industry only emerged several centuries after the invention of Woodblock printing in China in the 9th century, and of the printing press by Gutenberg in around 1436. These technologies eventually allowed for the mass production of flyers, poster and handbills, which lead to the first form of public space where these types of bills were posted – so called billboards.

The first record of a billboard being rented to an advertiser was quite some years later, in the USA in 1867. During that time, printing technology was limited to relatively small sheets of paper while large-scale advertisements, such as for example ones covering a big sign or an entire wall, were still required to be hand-painted. Out of that necessity emerged two separate type of companies, or departments of an ad agency: one being specialized on sign-painting and another one on so called “bill posting”, early names for what today we would call a creative agency and a media agency respectively.

In China shop advertisements were long dominated by large banners or flags as well as carved wooden signs. In the late 19th century however, we can find first Western-style displays, mural advertisements and billboards created by foreign trading firms or brands in foremost Shanghai. It was also there, where the first modern advertisement agencies of China were formed.

The first one likely was the Oriental Advertising Agency, created in 1909. This operation had been the ad department, art studio and workshop for manufacturing billboards of the French Oriental Press company founded in 1897, until it was spun out as an independent agency. Together with the British Harvey’s Advertising & Billposting Agency founded in 1910, these two companies dominated the early Shanghai billboard market alongside smaller competitors such as the China Publicity Company, which was a subsidiary of the Chinese-owned Commercial Press and was founded in 1913.

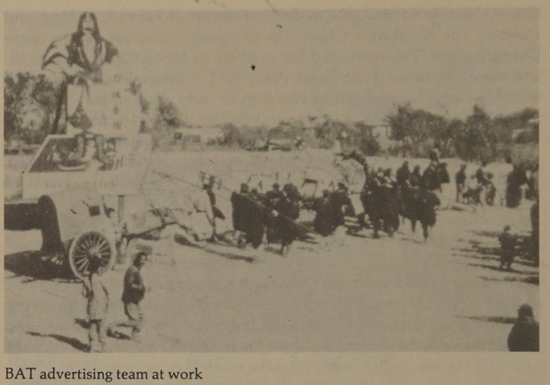

After the First World War, the largest operator of sign-painting and billposting services in all of China, was the inhouse advertisement department of British-American Tobacco (B.A.T.). At its peak in the 1920s and early 1930s, BAT employed over 25,000 workers in China, many of which were sales agents and out of home (OOH) advertisement staff. Besides plastering posters on walls, these outdoor teams advertised BAT’s cigarette brands on thousands of self-owned billboards and displays, which they erected at wharves, railroad stations, highway junctions and other transportation nexuses across the entire country.

Besides BAT, the most extensive advertising network during the early 1930s was, according to Paul French, the one of legendary American ad man Carl Crow.

Before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, he managed 15,000 of billboards along the Yangtze valley, renting them at a lucrative margin to his advertising clients.

This takes us approximately to the time of our advertisement painter, from a series of Japanese postcards titled “Manchurian Life”. The Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo was established in 1932 and before the war, BAT was still allowed operations in the country through its subsidiary Chi Tung Tobacco.

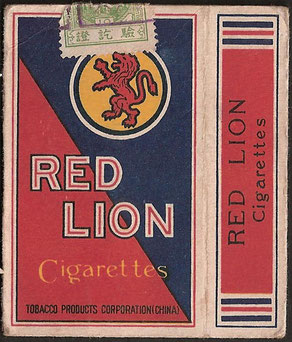

The postcard leaves us guessing for which brand of cigarettes the advertisement ultimately was created. All that can be made out are the characters 富贵, for “wealth”, and a lady pulling out an oversized cigarette from a round canister. The mural could have been an advertisement for a Chi Tung Tobacco brand or for a domestic manufacturer such as the Manchou Tobacco Co. The red and blue color palette of the packaging however points towards „Red Lion” cigarettes by the Tobacco Products Corporation China, also a company under B.A.T..

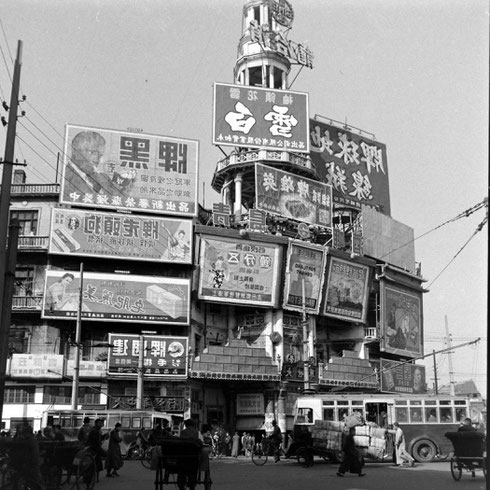

After the war and before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Western advertisements made a short comeback and so did the commercial signwriters and billboard painters. They were called wall dogs for two reasons: firstly, because they worked like dogs in all weathers and secondly, traversing up and down the side of a building meant they needed to be tethered to the wall. At least two prominent series of photos from that period in China, one from Jack Birns and one from Sam Tata, showing the repainting of a Lux soap billboard with Greer Garson, document the daring artist’s work responsible for the exuberant advertisements which gave Old Shanghai its unmistakable charm.

While many newspaper and magazine adverts, advertising posters and calendars from that era have survived, only very few billboards and mural advertisements, the remnants of which are referred to as “ghost signs”, can still be found in China — striking, spectral reminders of the first golden period of modern Chinese consumer culture.

Write a comment